Pro tips include avoiding “inspiration porn” and — yes! — quoting the people you’re writing about.

By Amy Silverman

When our newborn daughter was diagnosed with Down syndrome, my husband Ray and I just stared at each other.

I’d been a journalist for more than a decade, covering politics and social welfare. But I had never met anyone with Down syndrome; I knew nothing about it.

I thought hard and finally came up with an image from TV news of a young woman in a long dress, sash and a crown – short, smiling, with almond-shaped eyes.

“It’s not so bad,” I told Ray. “Sophie will be the homecoming queen of her high school! Neither you nor I ever even went to a homecoming dance. That’s something, right?”

That was my takeaway, after years of media consumption – that our daughter with disabilities would be homecoming queen.

Sophie is now 15, and the world has come so far in so many ways. Advances in early intervention, health care, and education mean that kids like her are thriving.

But there’s one important place where we still far short – and that’s producing nuanced journalism about people with disabilities.

Author Amy Silverman and her daughters in 2014

Yes, there are stories being told. Disability journalism is a hot beat right now. But just because you’re covering disability doesn’t mean you’re doing it right.

This is especially important in education reporting, since schools are such a vital part of the picture. And a place where journalism frequently fails.

The reality is that TV sitcoms are now tackling disability harder and better than most journalism. Smart television shows like “Atypical” on Netflix and “Speechless” on ABC tell the stories of high school students with autism and cerebral palsy head-on with humor and insight.

The characters are three dimensional – they laugh, cry, get in trouble. They are not angels. Their parents yell and scream to get them what they need in school.

In contrast, news outlets large and small are still passing off the heart-warming homecoming queen story as news.

These stories tend to air in the final minutes of a nightly newscast, designed to send you off to bed with a smile and renewed faith in humanity. The young girl named prom queen. The boy who sat on the sidelines all season, asked in the final moments of a game in which the team was comfortably ahead to make the “winning” basket. The student who overcomes a rare and exotic illness to make it to graduation.

The only real difference is that now there’s a name for it: inspiration porn.

Mercury News story that meets the author’s definition of “inspiration porn.”

The term was popularized in 2012 by Stella Young, a comedian, journalist and disability rights activist from Australia. (Young had osteogenesis imperfecta, also known as brittle-bone disease, and used a wheelchair. She passed away in 2014.)

Months before she died, Young gave a TED Talk entitled, “I’m Not Your Inspiration, “ arguing that disability does not make her – or anyone else – exceptional.

From her speech:

I use the term porn deliberately, because they objectify one group of people for the benefit of another group of people. So in this case, we’re objectifying disabled people for the benefit of nondisabled people. The purpose of these images is to inspire you, to motivate you, so that we can look at them and think, “Well, however bad my life is, it could be worse. I could be that person.”

But what if you are that person?

If you are that person, you might be tired of constantly being someone’s mascot.

Though there’s no definition that everyone agrees on, I see inspiration porn most often in education reporting, possibly because that is the arena in which people with disabilities are most visible.

In 2017-18, the Orange County Register ran a series on Riley McCoy, the “girl who can’t go out in the sun” because of a rare disorder called xeroderma pigmentosum.

In a story from June, the paper reported that McCoy wore a special hood that allowed her to stand in the sun for her high school graduation. The piece begins:

The sun has defined her. Scared her. Threatened to kill her. Driven her indoors. Forced her allegiance to the darkness.

There are evenings when she cries until the sun drops under the line of the horizon. Imagine being Riley McCoy, 18, constantly counting the minutes until night. The sun has stopped her from going with her friends to the beach or to the park, from sitting in the car with the window rolled down, from walking her dog, from just doing normal things on normal days.

In her short life, the sun has won.

But not today.

Media outlets of all sizes are guilty of producing superficial coverage when it comes to writing about kids with disabilities.

Check out this video posted by the Washington Post in January, of a boy with Down syndrome making a basket.

It doesn’t even bother to identify the student or the school.

Or this piece from the CBS Evening News, about a friendship between a young man with Down syndrome and a classmate.

It’s a sweet story, but it’s one-dimensional. Why do we give so much credit to a typical kid who is kind to a kid with disabilities? When will that not be something worthy of a big blue ribbon?

This Connecticut Public Radio series “uncovers serious injustice and still manages to focus on nuanced character development.”

Yes, it’s important to encourage journalists to tell stories about disability. But it’s equally important to move past the clichés and feel-good platitudes to talk about what it’s really like for kids with extra challenges (and, for that matter, the teachers, administrators, staff, parents, and community who surround them) to make their way through our education system.

There has been exceptional investigative reporting done on the lack of high-quality special education services, such as The New Yorker’s recent report on African-American boys being mistreated in Georgia’s special education program.

This horror story has meaning and depth because the reporter took the time to learn the intricacies of the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act – and how it’s not being applied.

Even more than that, the characters affected, not just the child but his family, were fully developed. It is hard to look away from the specific injustices detailed here, which make one wonder where else such problems exist.

There are some other standout examples.

With his excellent reporting on autism, David Desroches of Connecticut Public Radio uncovers serious injustice and still manages to focus on nuanced character development.

Over the course of many months, including for a September story, “For a Teen with Autism, Being Different Was Seen as Being Dangerous,” Desroches interviewed Owen Lynch, a Connecticut high school student with autism who has been a target of bullying after the Parkland shooting in Florida.

Desroaches also interviewed Lynch’s family, as well as education and mental health experts. He reviewed piles of documents related to Lynch’s experience and background.

The resulting pieces are heartbreaking, not heartwarming — and they tell a real, important story.

The story of AnnCatherine Heigl, a George Mason University student with Down syndrome who was rejected at every sorority at her school, went viral earlier this year. There were some elements of inspiration porn in the story that ran in Heigl’s hometown newspaper. But Inside Higher Education did a better job with a more straightforward approach that also featured reporting on how other campuses had handled the issue of students with disabilities applying to sororities.

Its only major problem is that it failed to include an interview with Heigl herself (or an explanation as to why there wasn’t one), which I consider a huge deficit.

In any story, it’s best to get to the source, right? Somehow that rule doesn’t apply in journalism about people with disabilities. It might be scary to interview someone with a disability, but it’s our job as journalists to tell true stories, and eliminating the subject is not acceptable.

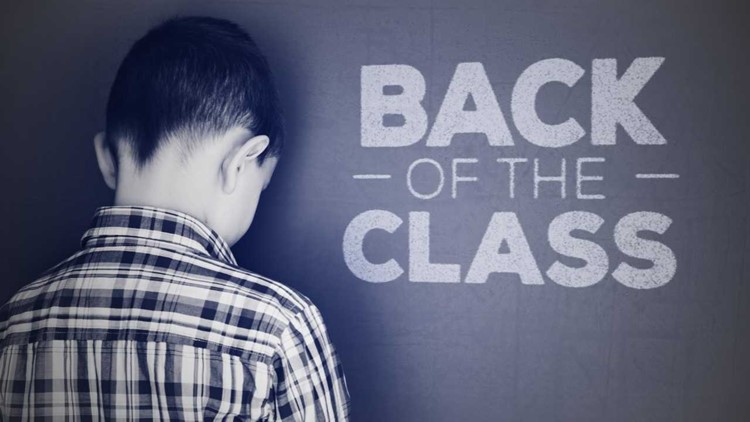

Back of the Class, a seven-part investigation by KING5’s Susannah Frame and Taylor Mirfendereski, was one of the winners of this year’s NCDJ disability journalism contest.

I know it’s not easy. Disability journalism can be treacherous: The acceptable language changes on what feels like a daily basis, privacy laws, and heel-dragging government types make it almost impossible to get your hands on records, and parents are often hesitant to speak up. Or, they have too much to say.

But there are some resources that can help. I’m on the board of the National Center on Disability and Journalism (NCDJ), housed at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University, and we had a record-breaking number of entries this year in NCDJ’s annual contest.

I spent much of the summer updating NCDJ’s Style Guide, which includes acceptable language for describing many disabilities not addressed by the Associated Press style manual. NCDJ is also offering training at conferences and materials on our website.

My favorite places are the gray ones – where life is real, not simply good or bad. That’s where my Sophie spends most of her time.

She’s fully mainstreamed as a sophomore in high school, no small feat. But she didn’t make the cheerleading squad or the musical. Kids are nice to her (sometimes) but she doesn’t have friends. She’s failing geometry but getting a B in chemistry. She won’t be the Homecoming Queen, but she had fun concocting an elaborate invitation to her older sister, who has agreed to be her date.

Sophie is making her way through high school like other kids do – it’s messy, but she’s doing it.

That’s the kind of story that we as journalists fail to tell, because it’s not super sexy. It’s uncomfortable. It’s real. But it’s the place where the true inadequacies of the system and the flaws and strengths of humans are revealed.

And it’s being done – just not enough.

Related work:

Education journalism’s diversity challenge

English-language learners make the front pages – but that’s not enough