Follow these 11 recommendations to avoid making the same mistakes!

By Alexander Russo

When the New York Times’ A1 story about an online education program hit the stands a week ago Sunday, it seemed like it was going to be a big hit with readers.

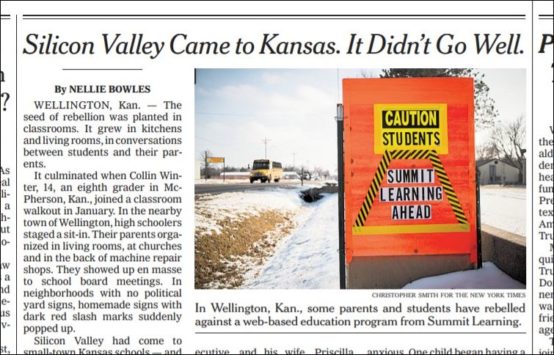

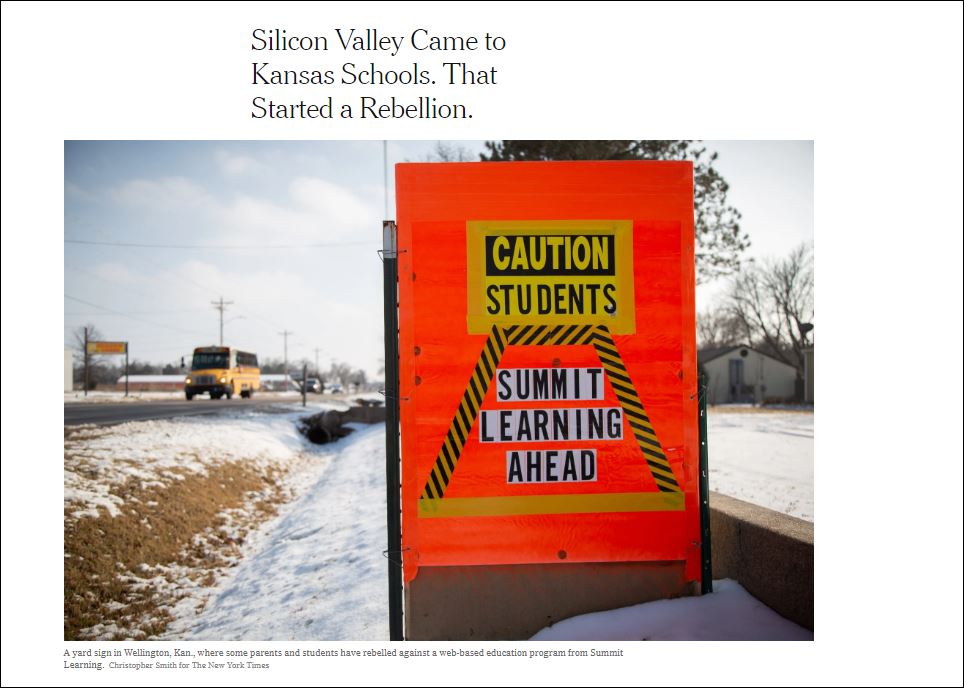

Focused on two small Kansas school districts that had implemented a new “web-based platform and curriculum” called Summit Learning last fall, the story describes how early enthusiasm for the idea had waned, leading to a local rebellion that was part of a growing national uprising.

“Silicon Valley had come to small-town Kansas schools — and it was not going well,” noted the story, written by tech reporter Nellie Bowles with additional reporting from Natasha Singer and edited by Pui-Wing Tam.

This wasn’t the first time that the Times had addressed concerns about technology and schools. But almost immediately, there were questions about the journalism behind this piece. The Times responded with two small corrections, but several other questions and concerns remain, including the lack of corroboration for claims involving the size and intensity of parent opposition that are central to the piece.

Upon close examination, the story’s own reporting doesn’t actually support the notion of a parent rebellion — in Kansas or nationwide. Just as important, the story details the concerns being expressed by these parents without helping us assess their merits.

How did this happen? What could have been done to avoid these problems? I spoke with the local superintendent whose efforts are the focal point here, as well as to Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), Summit Learning, and several others who participated in the story. The New York Times declined an interview.

Here are some of the lessons that have emerged:

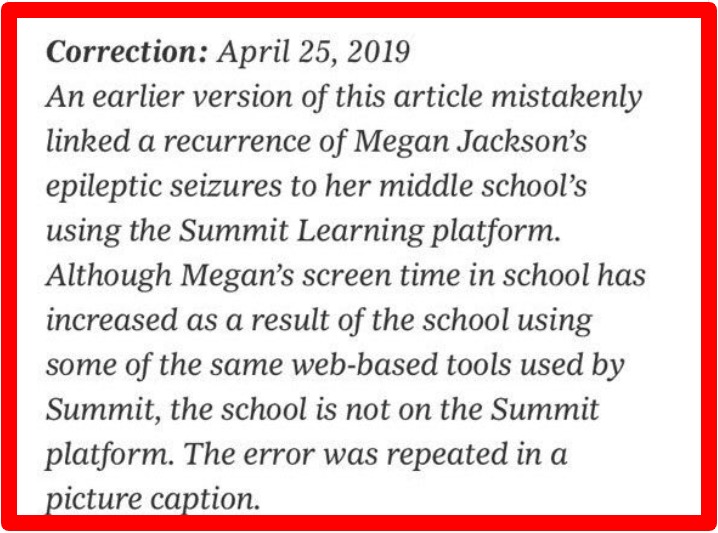

![]()

Wellington middle school student Megan Jackson (far left) was one of the students featured in the story. She turned out to have not been a participant in the Summit Learning program after all.

Lesson #1: Credit others’ work before you publish

The first sign of trouble came shortly after the story first published when it became clear that the Times had not appropriately credited Chalkbeat for its reporting on the research behind Summit Learning. To its credit, the Times corrected it quickly, adding a link to a line about how Summit “chose not to be part of a study” after having commissioned a study design. But ideally, the Times should have done that before publication.

Lesson #2: Fact-check your sources

Next, Wellington superintendent Mark Whitener issued a statement expressing his displeasure with the story and disputing several key facts in the story. And as it turned out, a 12-year-old middle school student who reported seizures after her school started using Summit wasn’t actually participating in the program. The Times corrected the error Thursday afternoon. “Yeesh this is a big correction,” tweeted freelance education reporter Rachel Cohen.

Lesson #3: Don’t forget the very basics!

The piece provides surprisingly little detail about the learning program at the center of the controversy. “Under Summit’s program, students spend much of the day on their laptops and go online for lesson plans and quizzes, which they complete at their own pace,” is what we’re told. That’s about it. But there’s so much more we’d like to know. How much time do the kids really spend staring at their computers? Is the program as bad as the protesting parents seem to think?

Sign up here for a free newsletter featuring the week’s best education news and newsroom comings and goings.

To see what Summit looks like from inside a school, check out this EdSurge story based on visits to two DC schools using Summit last year. Or read Kristina Rizga’s 2017 Mother Jones feature.

Lesson #4: Independent verification is your friend

Central to the piece is a claim that “about a dozen parents in Wellington” had left the district’s schools rather than participate in the program. The estimate was sourced to a city councilman but not independently verified by the Times. Councilman Kevin Dodds told me via email that the figure he gave to the Times came from a local Facebook group. In terms of official statistics, superintendent Whitener says that “the best we can tell is nine [students] have left” Wellington in protest against the program. The superintendent from McPherson has said in other news reports that 10 students have transferred out.

Lesson #5: For the love of God, pick a main example and stick to it!

Though the images and many of the voices accompanying the piece feature Wellington, the Times story toggles back and forth between two different Kansas school districts, Wellington and McPherson. This sets up a naturally confusing scenario for the piece, and as written, it’s easy to lose track of which school was involved with all the back-and-forth. A single focus would have been enormously helpful to readers and to the reporting process.

The online version of the Times story is headlined with a reference to a parent “rebellion” that does not turn out to be as substantial in size as might be expected, either locally or nationally.

Lesson #6: Careful about using that survey data

The Times story claims that 77 percent of McPherson parents expressed a negative view of the program. Here’s a link to the survey. However, the researcher who developed the survey told me in an email that he feels the Times story misrepresented the data because it fails to mention a low (42 percent) response rate and ignores more positive data from elementary school parents. “Our story accurately reflected the survey results,” responded Times spokesperson Danielle Rhoades Ha. Meanwhile, Wellington superintendent Whitener has stated that an internal, unpublished district survey of Wellington parents showed “80 percent had positive comments about Summit Learning.”

Lesson #7: Remember to give voice to a range of core stakeholders

Gordon Mohn, the superintendent of McPherson, was interviewed and quoted in the Times story, as was the principal of the Wellington high school. But Wellington superintendent Whitener says that neither he nor other members of the district team had been invited to participate. And I can’t recall any voices of parents, teachers, and students who like the program. That’s too bad because those voices would have balanced and deepened the piece. For example, Superintendent Whitener told me in a phone interview that he wishes that he’d started with a smaller group of volunteer students and teachers and then grown from there. “People like having choices,” he said.

Lesson #8: Beware overreaching your reporting (part 1)

The Times story describes a local “rebellion” against the web-based education program in Wellington. The abundance of protest signs depicted in the piece, along with the anecdotes from students and parents opposed to the program, suggest broad appeal. But a meeting of opponents is described as having a dozen parents and students in attendance. A student walkout in McPherson is reported to have numbered 50 students (out of 472 in the program at that school). The parents protested at a school board meeting “en masse,” which could be 10 parents, or it could be 100. You get the idea. The numbers just aren’t there. Visual evidence is limited to a handful of protest signs. Parent opposition to the program has been “not huge, but really loud,” consisting of a core group of parents Whitener estimates at roughly 20 in number.

Lesson #9: Beware overreaching your reporting (part 2)

By giving the story such prominent placement, the Times is telling readers that something big and important is going on. The story describes “mounting nationwide opposition” to the program. But then it cites only five examples: a student walkout in Brooklyn, a rollback in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and a cancellation in Cheshire, Connecticut in addition to the two Kansas districts. These parents and students who oppose Summit may be sincere and intense, but they don’t appear to be representative of a larger movement. The Summit program is in roughly 380 schools nationwide.

Above: The Times’ correction, appended to the bottom of the story on Thursday afternoon.

Lesson #10: Make your correction prompt, prominent, & clear

When it finally corrected the story, the Times placed its correction at the very bottom of the story with no indication at the top that there was any corrected material. Only the hardiest readers would have much chance of seeing what happened. Making matters worse, the correction itself was vague and sloppy, confusing as much as it clarified. And the accompanying statement isn’t much help. “Reporters are human so make mistakes but nothing (even my antipathy to both Zuckerbergs) justifies deplorable way @nytimes deals w/ mistake in Summit story,” tweeted education reporter Gail Robinson.

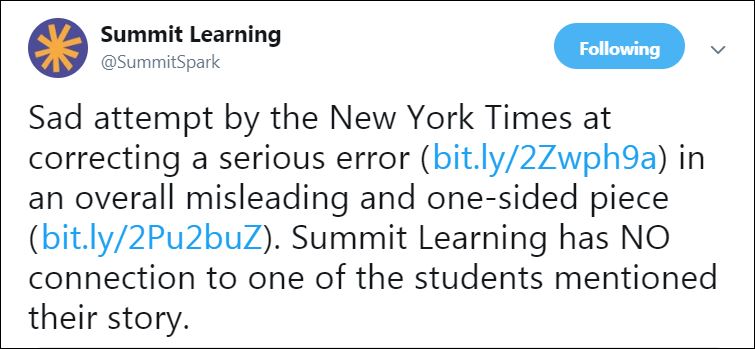

Lesson #11: Be prepared for strong public pushback, even after you correct

It used to be that organizations that didn’t like a story didn’t dare go public with their complaints for fear of ruining relationships with reporters. Even the smallest correction was treated as if it was gold. But that’s obviously no longer the case. Summit Learning called the Thursday fix to the story a “sad attempt by the New York Times at correcting a serious error.” The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative described it as a “big correction” that still doesn’t go far enough…”

Here’s Summit’s somewhat Trump-like response to the Times’ correction.

The desire to write a compelling story about a controversial new approach to teaching is entirely understandable. Combining several themes of the day — dislike of Facebook, the fear of technology, and skepticism towards philanthropists — the protest narrative is compelling and important. Clearly, the concern among the protesting parents is intense.

But in taking the protesting parents’ concerns so literally, joining in and amplifying their highly alarmed view of the situation, the piece misses a major opportunity. We learn what they believe, but not why their beliefs have become so much stronger than the rest of the community. And their beliefs are never really matched up against what’s actually going on in the program, which we never see.

Something difficult and important is going on in the Wellington and McPherson schools — both of which are said to be adding an opt-out alternative to the online learning program next year. It’s a shame that the Times story didn’t give readers that richer, more nuanced story.

Related columns from The Grade:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/