Increasingly, big education stories in Connecticut go uncovered — or are noted by only a single outlet — reports guest columnist David DesRoches in this new look at the Hartford Courant, CT Post, CT Mirror, and Connecticut Public Radio.

By David DesRoches

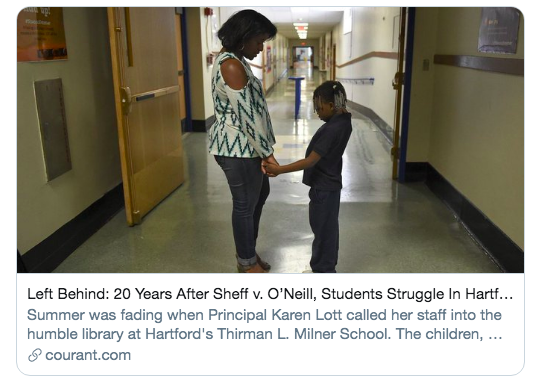

A 2018 lawsuit claims that a decades-long school desegregation program in Connecticut’s state capital harms students of color. If the plaintiffs prevail, 30 years of integration efforts could be sent back to square one.

But relatively few people know about the case, Robinson v. Wentzel, perhaps because many news outlets have hardly covered it.

Marie Shanahan, associate journalism professor at the University of Connecticut and former reporter with the Hartford Courant, said she hadn’t heard about the case, which is being bankrolled by the Pacific Legal Foundation, a libertarian-leaning organization.*

But Shanahan doesn’t blame education reporters for missing the story. For her, it’s a reflection of larger trends in the journalism industry.

“Part of it, honestly, is the news cycle is like a torrent every single day,” Shanahan said. “We only have so much bandwidth to pay attention to certain things.”

The other obvious factor is the decline in the number of full-time education reporters.

As has happened across the nation, cutbacks and buyouts at Connecticut news outlets have resulted in more meager education coverage, especially at the statewide level. Important stories have gone all but uncovered.

Or, if they do receive attention, it’s from a single outlet rather than two or three.

The result is a much less informed public.

For more on the challenges facing education journalism today, read our February column about the brain drain in education journalism or the 2018 look at the dwindling number of fulltime education journalists in the San Francisco Bay Area.

None of the reporters who worked on this award-winning 2017 Hartford Courant series is at the paper any longer.

It used to be that 10 reporters covered state board of education meetings, according to Linda Lambeck, who’s been covering education at the Connecticut Post for more than three decades.

Now, if there’s more than one, “a little cheer goes up at the state board of ed because they feel like they’re being watched,” Lambeck said.

Years ago, the nation’s oldest newspaper, the Hartford Courant, employed several reporters to cover higher education, K-12, local schools, and statewide policy.

Now, the paper doesn’t have anyone focused solely on schools. It published a story on the lawsuit when it was filed but hasn’t examined the issue with any depth since. The Connecticut Post and Connecticut Public Radio have also barely covered the case.

Ironically, it was the Courant’s 2017 series about the unintended consequences of school desegregation that eventually led to the Robinson lawsuit. All three of the reporters who worked on that 2017 series — which won an investigative reporting award from the Education Writers Association — are no longer with the paper.

That’s not the only example. For nearly five years, Connecticut Public Radio had a full-time education reporter — me — until the grant funding my position ended this past summer. The Connecticut Post has also slowly scaled back its education coverage over the years, though it recently hired a one-year fellow to cover higher education.

As a result, the number of journalists covering statewide education stories dropped from four to two during the past year: Kathy Megan, a longtime education reporter who left the Courant to join the Connecticut Mirror, and Lambeck at the Connecticut Post are still on the beat.

Follow The Grade on Twitter and Facebook to learn more about how the media covers education.

The CT Mirror has become one of the strongest, most consistent sources for education news in the state.

The Robinson v. Wentzel case involves an effort by Hartford, which is majority African American and Latino, to integrate schools by attracting white students from the suburbs to high-performing magnet schools in the city. To keep the student populations diverse, a limit is placed on the number of African-American and Latino students who can attend these schools.

If too few white students enroll, that leaves some seats open — seats that the plaintiffs say should go to students of color who are otherwise stuck in underfunded and underperforming neighborhood schools. A second lawsuit challenges a state law that recently imposed similar rules for all Connecticut magnet schools.

The only Connecticut-based journalist in the state who examined the case in any depth was Jacqueline Rabe Thomas, a reporter for the nonprofit Connecticut Mirror.

“Am I disappointed that the Mirror is the only one doing deep dives on this issue now? Of course,” Rabe Thomas wrote in an email. “There are huge public policy implications for this case.”

Rabe Thomas was also the only reporter to sit through a previous landmark school lawsuit, CCJEF v. Rell, for the entire five-month trial in 2016. Her work culminated in a seven-part series, Troubled Schools on Trial, which was a finalist for an Education Writers Association award.

The judge in the case agreed with the plaintiffs that poor districts were unfairly underfunded and ordered the state’s education funding formula to be overhauled; the Connecticut Supreme Court later overturned the decision.

The Connecticut Mirror is an outlier, Rabe Thomas said. While it does publish daily news, it focuses more on public policy issues and gives its reporters freedom to dig in.

“I’m fortunate,” Rabe Thomas said. “When I told them I wanted to [cover the trial], they didn’t say, ‘Why? No, you can’t do that.’ They said, ‘OK, let’s do that.’ “

As the only reporter in the courtroom for the entire trial, though, she felt a heavy burden.

“This is sort of a once-in-a-generation trial, and there’s one reporter in the room,” Rabe Thomas said. “And that weighs really heavily on me. Like, how do I report on this?”

“There should have been more people there listening to all the testimony,” said Megan, who was with the Courant at the time. She had covered the opening statements, but was taken off the story by her editor to write a feature, and another reporter, unfamiliar with the case, was assigned to cover the closing arguments.

Questions were sent to editors at the Courant, the Connecticut Post, and Connecticut Public Radio to figure out what their plans are for covering education moving forward. None provided any comment.

Each week, The Grade takes a deeper look at education journalism. Sign up for the free newsletter.

For the CT Post, Linda Lambeck covers both state and local education issues.

The shortage of education reporters also has affected coverage of the state Legislature, with some important education-related legislation being missed. A 2017 law that led to the school-integration lawsuits also went largely unnoticed, said Chris Peak, a journalist who covers education, housing, and law for the New Haven Independent.

“There was this pretty drastic thing that happened in the Legislature unanimously that we totally missed,” Peak said. “I didn’t see any news coverage about it.”

Some of the missed legislative stories could be an unintended consequence of coverage of the legislative session by CTN, a publicly funded television station similar to C-SPAN. CTN broadcasts public hearings, committee meetings, votes, and other public business live on its website, and it’s become a staple in newsrooms around the state.

But it also has contributed to fewer reporters attending legislative events in person. “I used to spend a lot more time covering education committees,” Lambeck said. “I think I maybe went up there once this past [session] for a public hearing.”

UConn’s Shanahan said one solution could be the creation of a nonprofit news outlet dedicated solely to statewide education journalism, similar to how the Connecticut Health Investigative Team covers health.

“They cover the nursing board, and they cover them every single month,” Shanahan said. “As a result of that, there’s actually an archive that they can trace and they can see trends.”

The Connecticut Mirror has attempted to fill the void. Several news organizations are now partnering with the nonprofit to run its stories, including the Hartford Courant and Hearst Connecticut Media, which owns the Connecticut Post.

But the wider distribution of one voice does not address the problem of a limited number of news sources.

The Post’s Lambeck pointed out that the partnership with the Mirror has taken some of the burden off her to stay on top of the broader state issues, but it also limits perspectives. “When [Megan] comes out with a big story, my first reaction is, ‘Oh shit, I didn’t know that,’ ” Lambeck said. “And then the second is, ‘Oh, I don’t have to know that because Kathy did the story.’ But the flip side of that is, you know, there’s no two perspectives.”

Several of the reporters shown above who have written about education in Connecticut are no longer doing so, are splitting time covering other beats, or are doing so on a temporary basis.

Since January, Rabe Thomas has been writing about housing discrimination through a partnership with ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network.

The Mirror hired Megan to cover the beat in Rabe Thomas’ absence. It’s unclear what she’ll do at the end of the year when her term expires, or what the Courant’s plans are for statewide education coverage going forward.

Then, of course, there are the two lawsuits, which might be merged.

When the state’s attempt to integrate schools finally comes to trial, it’s unknown which, if any, reporters will be sitting in the courtroom listening for the tree to fall.

*Correction: The original version of this column incorrectly connected the Pacific Legal Foundation to an anti-affirmative-action lawsuit against Harvard. The foundation was not a participant.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David DesRoches

David DesRoches has been a journalist for 10 years, spending the last five covering education for WNPR public radio. He also co-founded a nonprofit media company in Ethiopia, and is starting at Quinnipiac University later this month as the director of community programming. He can be found on Twitter at @SavingEJ.