After decades of top-down school management, new models of collaborative teacher leadership have begun to emerge.

It is increasingly implausible that we could improve the performance of schools . . . without promoting leadership in teaching by teachers.

—Judith Warren Little (1988)

Just over 30 years ago, Judith Warren Little, one of our nation’s most prominent scholars of the teaching profession, issued a clarion call for teachers to lead school reform. At the same time, though, she argued that it will not be possible for teachers to lead effectively unless and until we see significant changes in how power and authority are distributed within schools.

Today brings us promising signs that principals and teachers may finally be ready to step away from the long-standing hierarchical leadership structures that characterize public education. To be sure, teachers have always served as grade-level chairs or department heads, although “for teachers these assignments were not always viewed meaningfully in terms of leadership” (Little, personal communication, January 2019). However, the prospects for meaningful teacher leadership look far brighter now than ever before.

For example, in response to the demands of standards-based school reforms, growing numbers of teachers have taken on significant leadership roles related to curriculum implementation, professional development, and induction and mentoring. Further, countless teachers have stepped forward to organize and lead professional learning communities (PLCs) in their grades or subjects, sharing practices and using test score data to improve outcomes for their students (Berry, Byrd, & Wieder, 2013). Moreover, the majority of administrators have come to recognize that they can’t provide all the leadership their schools need, and sizable numbers of teachers say they are willing and eager to contribute. According to a nationwide poll, 3 out of 4 principals believe their jobs have become “too complex,” and 1 in 4 teachers are “very/extremely” interested in both teaching and leading in hybrid roles (MetLife, 2013).

The top-down, fix-the-teacher education reforms of No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top are losing favor.

I am no Pollyanna. I’m fully aware that, in early 2019, enormous obstacles continue to face the teaching profession in the United States — low salaries, high turnover, and too many underprepared recruits entering the classroom, to name just a few. Even the Wall Street Journal, rarely an advocate for educators’ professional aspirations, recently noted that because of “small raises, budget frustration and opportunities elsewhere,” teachers are leaving their jobs in “record numbers” (Hackman & Morath, 2018). Similarly, given the accountability measures still in place in many states and the strict lesson plans and pacing guides in place in many districts, I see few opportunities today for the emergence of what I call “teacherpreneurs,” or teachers who seize the initiative to design their own curricula and lessons and create their own classroom tools and materials to better serve their students (Berry et al., 2016). I understand also that most educators remain isolated from one another. A recent RAND survey found that only 53% of the nation’s teachers strongly or somewhat agree that they have sufficient opportunities to collaborate with their colleagues, and only 38% agree they have sufficient time to do so — and even among teachers who strongly agree they have opportunities to collaborate with colleagues, 69% report they never or rarely (approximately once per month) observe a colleague’s classroom (Johnston & Tsai, 2018).

Even so, I am optimistic. Consider four developments that bode well for teacher leadership in the years ahead: (1) evidence on the positive effects of teacher leadership continues to mount, (2) increasingly, local and state policies are codifying and recognizing teacher leadership, (3) teacher leaders are becoming more proficient at using educational technology and sharing their expertise through digital media, and (4) researchers are deepening their knowledge about how teachers learn to lead effectively.

New evidence on the effects of teacher leadership

Researchers, using a variety of methods, have found strong evidence of the positive effects of teacher leadership. Three sets of studies are particularly instructive, and as I will point out later, have begun to pave the way for educators to do a better job of cultivating teacher leadership.

First, Matthew Ronfeldt and colleagues (2015), drawing on several years of data from more than 10,000 teachers in Florida’s Miami-Dade Public Schools, found that teachers improve their practice at greater rates when they work in schools with better quality collaboration. Joint work on student assessments was often significantly predictive of achievement gains across math and reading. Teacher collaboration matters for student learning, and it matters for how teachers learn to lead.

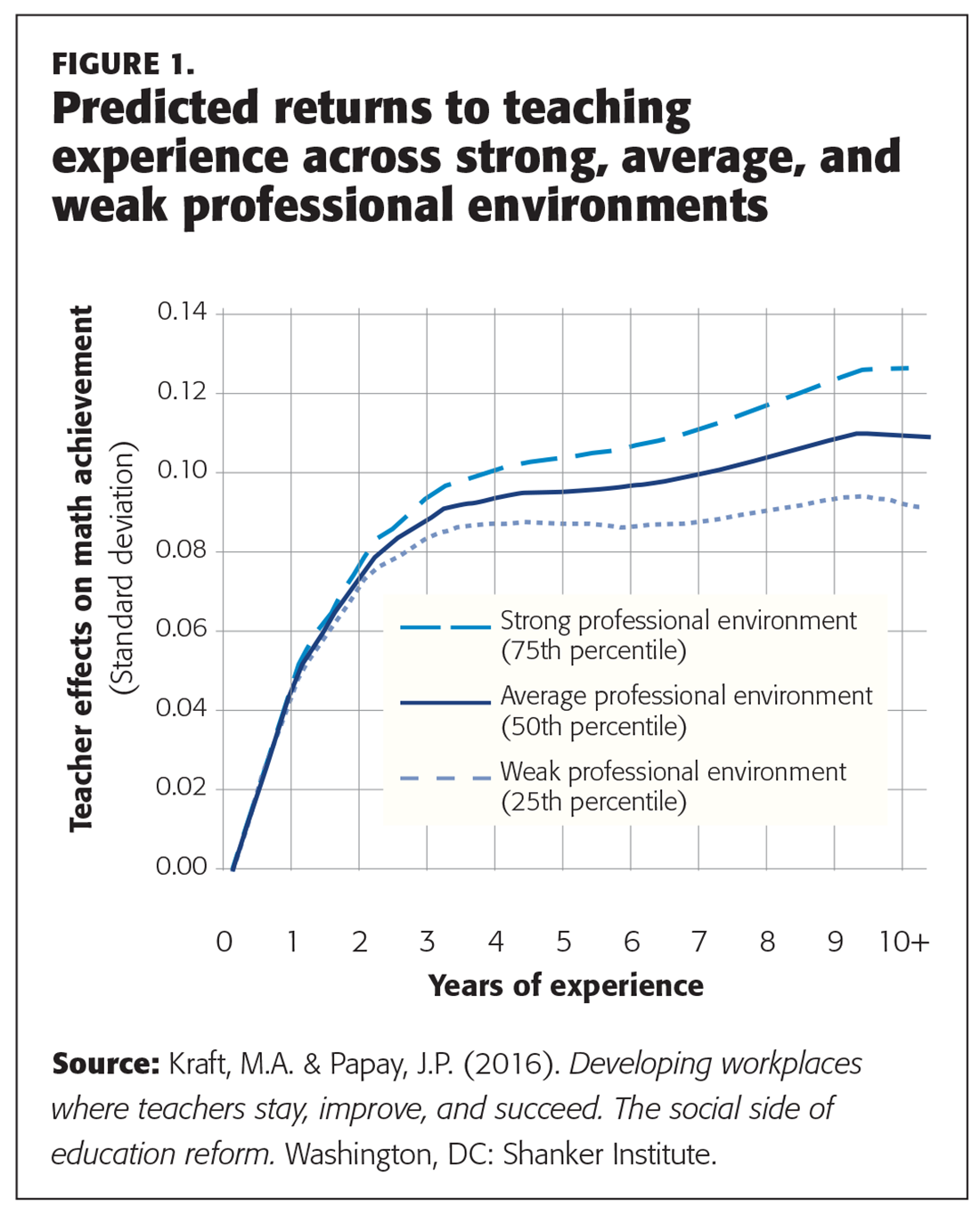

Second, John Papay and colleagues (2016) found higher student scores on reading and math tests when higher- and lower-performing teachers were “encouraged to scrutinize each other’s evaluation results, observe each other teaching in the classroom, discuss strategies for improvement, and follow up with each other’s commitments throughout the school year.” And in a related study, Matthew Kraft and John Papay (2016) found that teachers working in schools with strong professional working environments were much more likely to improve over several years — 38% more than peers in schools with weak environments (see Figure 1).

Finally, using survey and test score data across 16 states, Richard Ingersoll, Philip Sirinides, and Patrick Doughtery (2017) examined the relationship between teacher decision making (and by extension, leadership) and school performance. They found that schools with the highest levels of overall instructional leadership from teachers have substantially higher mathematics and English language arts test scores in their state compared to those where teachers report low levels of teacher leadership in these areas.

New policies codifying teacher leadership

Over the last several years, many states and school districts have created policies that encourage teachers to lead from the classroom. For example, 17 states have adopted teacher leader standards, 22 states now offer a license or endorsement, and 24 provide formal supports and/or incentives for classroom practitioners who lead (Diffey & Aragon, 2018), and more than a dozen states now offer ways for teachers to demonstrate what they know and can do in efforts to lead their own professional learning. As a result, at least five approaches to developing and supporting teacher leadership have begun to emerge:

First is the creation of distinct new leadership roles and opportunities, including well-known career ladder programs in districts such as Baltimore, Denver, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. In Washington, for example, teachers who have demonstrated teaching effectiveness have opportunities to be appointed by administrators to serve in various leadership roles (such as curriculum writer), mentor less experienced teachers, and earn additional bonuses for teaching in high-need schools. In the charter sector, Green Dot’s Animo Data Fellows program trains teachers to be data experts at their schools; and in several Uncommon Schools, a few teachers carry a reduced teaching load, giving them time to observe and provide feedback to a group of their peers at least once a week (Teach Plus, 2015).

Second, state education agencies are creating programs to spur teacher leadership. For example, Tennessee has created new leadership opportunities for teachers as part of a larger set of teacher evaluation reforms that have shifted from just assessing teachers to growing their practice (Douglas, 2015). The number of teachers reporting that their teaching evaluations improved their teaching doubled between 2012 and 2017, and 59 districts are now experimenting with teacher leadership models designed to increase student achievement (Olsen, 2018).

Similarly, Iowa has piloted a formal teacher leader program, with an investment of over $300 per student (adding up to roughly $150 million) to launch the effort. Over the last several years, approximately 10,000 Iowa teachers have served in some formal leadership role, with a recent evaluation suggesting the effort has improved the “application of professional development to classroom practice” and “the degree to which teachers collaborate with and learn from one another” (American Institutes for Research, 2018). As one superintendent reported, these efforts have given classroom practitioners “the courage and opportunity” to lead, and administrators are now finding ways to “fund teacher leadership rather than another program or professional development provider” (Berry & Eubanks, forthcoming).

Third, the Teacher Powered School (TPS) movement, while still nascent, has grown to about 120 sites in 19 states where classroom practitioners, working in teams, have autonomy to design and run schools. Instead of drawing on a few teachers to lead in the current hierarchical structure, TPS seeks to transform the structure as teachers lead in ways that personalize learning for their students. The vast majority of the public (85%) and teachers (78%), according to a 2014 national poll, believe creating such schools is a good idea (Education Evolving, 2014).

Fourth, the National Education Association has launched a wide array of programs — including the Teacher Leadership Institute — to develop the leadership capacity of paraeducators, teachers, and instructional coaches in ways that dramatically benefit students, public schools, and the well being of communities. Granted, for decades the leadership of the nation’s largest teachers union has called for professionalism (Chase, 1998). Perhaps now, though, in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2018 Janus decision — which ruled that unions can’t compel nonmembers to pay dues — teacher associations will shift their organizing power from mostly “bread and butter issues” to helping its members improve their teaching, while still tending to social justice reform in public education (Anderson, 2018).

Finally, over the last several years there has been a dramatic rise in teacher networks such as those hosted by EdCamp, the National Blogging Collaborative, the National Geographic Society, the National Network of State Teachers of the Year, Teach Plus, Hope Street, TeachingPartners, and the Teachers Guild, as well as my own organization, the Center for Teaching Quality (CTQ). In spite of the highly bureaucratic organizations in which most teachers work, these networks are beginning to break down long-standing barriers that have isolated individual practitioners. With colleagues at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, we have estimated that about 1 in 3 teachers now participates in at least one teacher network (Wendy Sauer, personal communication, April 2017).

More from Barnett Berry:

- The dynamic duo of professional learning = collaboration and technology

- Solving the teacher shortage: Revisiting the lessons we’ve learned

- Microcredentials: Teacher learning transformed

Teacher leaders using technology to redesign schools

Teachers everywhere are finding creative ways to use digital technology to redesign their schools in ways that emphasize 21st-century competencies, such as collaboration, problem solving, and self-directed learning. Over the last several years, for example, the Next Generation Learning Challenge has identified and provided support to dozens of such schools. Similarly, teachers all over the world are connecting their students online, trying out new virtual reality (VR) tools, and experimenting with other previously unimaginable forms of teaching and learning. And some of the same e-tools are being adapted to the world of teachers’ professional development, too, helping them break out of the professional silos that have long characterized education.

For example, companies like LearnZillion (http://learnzillion.com) deliver blended professional development to educators, with a focus on teaching them to produce and use their own online curriculum resources. In 2014, roughly 9 in 10 teachers used the internet to find or share lesson plans (e.g., on Pinterest and YouTube, often featuring classroom videos they’ve created themselves, in order to share best practices; Scholastic, 2015), 2 in 3 went online to get professional advice, and 6 in 10 used the internet to collaborate with colleagues they wouldn’t otherwise have met.

Further, 3 in 4 of today’s teachers choose to seek out informal professional learning opportunities, which has given rise to a fast-growing microcredentialing movement, in which teachers are able to demonstrate and document new skills and competencies through digital badging (CTQ & Digital Promise, 2017). In other words, technology is allowing teachers to learn from and connect with each other in all sorts of new ways, helping them “strengthen their identities as agents of change” (Cheung et al., 2018).

New evidence on how teachers learn to lead

Recent research has shed light not just on the benefits of teacher leadership but also on the ways in which teachers become leaders. For example, Dylan Wiliam (2014) has found that teachers learn best from colleagues and supervisors who help them take risks and embrace their weaknesses. Further, in studies of teachers who used formative assessment to boost student learning, he found that teachers improve their teaching most when they serve as resources for one another and develop a sense of ownership of their professional development. In other words, the most powerful professional learning tends to be shared among colleagues, not “vested in one person who is high up in the hierarchy” (York-Barr & Duke, 2004).

To develop teacher leaders, it’s not enough just to appoint a few teachers to be instructional coaches.

To develop teacher leaders, then, it’s not enough just to appoint a few teachers to be instructional coaches, who provide others with one-to-one support. Rather, this kind of learning is more of a “socially distributed phenomena” that develops over time, among members of a group. As teachers gain efficacy, they must have opportunities to reflect on what they master in the context of structured collaboration (Szczesiul & Huizenga, 2015).

Using social networking analysis tools, researchers such as Bill Penuel and Alan Daly have found that teachers are most likely to make instructional shifts and improve student learning when they have indirect exposure to new ideas through collegial interactions (Daly et al., 2014; Penuel et al., 2012). Similarly, Cynthia Coburn and Jennifer Russell (2008) found that while the strength and depth of teachers’ learning networks tend to vary considerably, the most productive networks “almost always stretch beyond grade-level groups to include others inside and outside the school.”

Most current teacher leadership models rely on a traditional human capital approach, with a primary, if not sole, focus on cultivating the skills of the individual teacher. This strand of research offers new ways to inform how school districts also can develop social and professional capital by cultivating, identifying, and leveraging collective expertise (Berry, 2016).

Five key issues

The top-down, fix-the-teacher education reforms of No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top are losing favor (Hess & McShane, 2018), and some of the nation’s most influential education philanthropies are calling for more “collaborative visioning” and tools and processes to assess “collective impact” in closing achievement and opportunity gaps in our nation’s schools (e.g., Srinivasan & Archer, 2018). The embrace of improvement science, in which teachers and administrators work together to strengthen their school, is becoming more prevalent in both rhetoric and action (Sparks, 2018).

Next-generation reform needs to include efforts to document the contributions teacher leaders, and how their influence spreads in a system of continuous school improvement.

Yet, there remains much more work ahead. As Judith Warren Little pointed out 30 years ago, in a comment that is still germane today, “The prospects for teacher leadership [will] remain dim if no one can distinguish the gains made for students when teachers in large numbers devote their collective attention to curriculum and instruction” (Little, 1988). In the long run, she argued, the success of teacher leadership will depend on how schools address five related issues. I reuse her headings here (in italics), along with my own thoughts on the prospects for teacher leadership in 2019 and beyond:

- The work teacher leaders do.

Every day, teacher leaders make critical contributions to the success of their colleagues and students. However, their efforts are not widely known to policy makers and the public (or even, in many cases, their own administrators). Americans have high levels of trust and confidence in teaching professionals in general (see the 2018 PDK poll), but much needs to be done to help the public understand the value of teacher leaders in particular. Next-generation reform needs to include efforts to document the contributions teacher leaders make, what gives rise to it, and how their influence spreads in a system of continuous school improvement.

- The symbolic role that teacher leaders assume.

Teacher leadership ought to be understood as a way of helping one’s colleagues improve, not as a means of fixing those who are underperforming. To that end, states and districts should invest in new tools for analyzing social networks to document the ways teachers influence their colleagues and to what end. Improving schools depends on understanding how teachers share their expertise with each other; who does so effectively; and, as Little puts it, how to make “more public the exemplars of rigorous, rewarding professional relationships.”

- The agreements for getting started.

Many school communities have created new labor-management agreements that ease up on old, highly restrictive rules governing how unions, districts, teachers, and administrators work together. For example, the NEA has (in non-bargaining states) negotiated agreements with districts to recognize and reward teachers who attain microcredentials, which may spur many teachers to take a more active role in seeking out and directing their own professional learning. Local NEA affiliates, such as in Jefferson County (Ky.) and Clark County (Nev.) have led their districts in using microcredentials, and new technological tools to support teacher-led learning and recognition for it. These school communities are setting the stage for unions and districts to work together in creating the variegated leadership roles and responsibilities needed for the profession’s future, rather than the fixed career paths of the past.

- Incentives and rewards that favor collaboration.

School districts must rethink school schedules to create time for teachers to both teach and engage in collaborative efforts to improve instruction. Most districts do not have the resources to offer teachers several weeks of professional development (such as the Summit Public Schools, in California and Washington, have been able to do). But countless schools have found ways to rearrange their schedules and assignments to give teachers at least three to five hours a week to collaborate and lead in authentic ways. And new teaching evaluation processes can help create incentives to share teaching expertise, such as by recognizing teachers as accomplished only if they can demonstrate how they help their colleagues improve.

- The policies that connect the leadership work of teachers and administrators.

I suspect that teacher leadership won’t really take off until school leadership programs (in universities, districts, and nonprofits) begin to prepare teachers and principals together. Only by experiencing authentic collaboration with teachers can administrators become confident in teachers’ capacity to lead and in their own ability to cultivate teachers’ leadership skills. One hopeful sign is that a number of states, including South Carolina, Georgia, and Arkansas, have begun to experiment with CTQ in building ground-up models of collective leadership where teachers and administrators are cocreating strategies to address the problems of practice they identify. For them, school leadership is no longer just the province of the principal and a few teachers. As Allen Kirby, principal of Walker Gamble Elementary in Clarendon County (S.C.), told me recently, “All the knowledge that is needed to transform teaching and learning is already in the building.” And Jessica Boyington, a teacher colleague of Allen’s who crafted her own hybrid teaching role, responded, “And this is why everyone wants to teach for their entire life at this school.”

I am optimistic that new organizational models, emerging in the private sector and fueled by the new economy, will challenge existing organizational life in our public schools. The complex work of school reform, now and in the future, needs to be driven by new approaches to governance, relying on informal networks rather than the assumption that a few individuals should “own, know, or control what everybody else does” (Heimans & Timms, 2014). Over the last 30 years, considerable progress has been made in elevating teacher leadership. New research and technologies are supporting teachers’ capacity to lead and overcome long-standing school structures and cultures that impede their leadership work. Frustrated with decades of centralized reforms, teachers are beginning to take ownership of school improvement efforts grounded in the daily work of their classrooms. It’s time for them — along with leaders of schools, districts, charter networks, and state education agencies — to take advantage of the opportunities that have emerged since 1988.

References

American Institutes for Research. (2018). Strategies for implementing the teacher leadership and compensation program in Iowa school districts. Washington, DC: Author.

Anderson, J. (2018). Changing the frame: A vision for comprehensive teacher unionism in a post-Janus environment. Lombard, IL: Consortium for Educational Change.

Berry, B. (2016). Transforming professional learning: Why teachers’ learning must be individualized — and how (Paper commissioned by the Pearson Corporation). Carrboro NC: Center for Teaching Quality.

Berry, B., Byrd, A., & Wieder, A. (2013). Teacherpreneurs: Teachers who lead without leaving. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Berry, B. & Eubanks, S. (forthcoming). Teacher leadership: Accelerating professional learning from inside the National Education Association. Carrboro, NC: Center for Teaching Quality.

Chase, B. (1998). NEA’s role: Cultivating teacher professionalism. Educational Leadership, 55 (5), 18-20.

Cheung, R., Reinhardt, T., Stone, L., & Little, J.W. (2018). Defining teacher leadership: A framework. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (3), 38-44.

Coburn, C.E. & Russell, J.L. (2008). District policy and teachers’ social networks. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 30 (3), 203–235.

CTQ & Digital Promise. (2017, October). Teacher micro-credentialing movement continues. Carrboro, NC: Authors.

Daly, A., Moolenaar, N.M., Der-Martirosian, C., & Yi-Hwa L. (2014). Assessing capital resources: Investigating the effects of teacher human and social capital on student achievement. Teachers College Record, 116 (7), 1-42.

Diffey, L. & Aragon, S. (2018). 50-state comparison: Teacher leadership and licensure advancement. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States.

Douglas, E. (2015, January 15). Six lessons on the power of teacher leadership [blog post]. Education Week.

Education Evolving. (2014). Teacher-powered schools: Generating lasting impact through common sense innovation. Saint Paul, MN: Author.

Hackman, M. & Morath, E. (2018, December 28). Teachers quit jobs at highest rate on record. Wall Street Journal.

Heimans, J. & Timms, T. (2014, December). Understanding ‘new power.’ Harvard Business Review.

Hess, F.M. & McShane, M.Q. (2018). The happy (and not so happy) accidents of Bush-Obama school reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (4), 31-35.

Ingersoll, R., Sirinides, P., & Doughtery, R. (2017). School leadership: Teachers’ roles in school decision-making, and student achievement. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

Johnston, W.R. & Tsai, T. (2018). The prevalence of collaboration among American teachers: National findings from the American Teacher Panel. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Kraft, M. & Papay, J. (2016, April). Developing workplaces where teachers stay, improve, and succeed. Washington, DC: Albert Shanker Institute.

Little, J.W. (1988). Assessing the prospects for teacher leadership. In A. Lieberman (Ed.), Building a professional culture in schools (pp. 78-106). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

MetLife Corporation. (2013). The MetLife survey of the American teacher: Challenges for school leadership. New York, NY: Author.

Olsen, L. (2018). Scaling reform: Tennessee’s statewide teacher transformation. Washington, DC: FutureEd.

Papay, J., Taylor, E.S., Tyler, J., & Laski, M. (2016, February). Learning job skills from colleagues at work: Evidence from a field experiment using teacher performance data. Washington, DC: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Penuel, W.R., Sun, M., Frank, K.A., & Gallagher, H.A. (2012, November). Using social network analysis to study how collegial interactions can augment teacher learning from external professional development. American Journal of Education, 119 (1), 103-136.

Ronfeldt, M., Farmer, S.O., McQueen, K., & Grissom, J. (2015). Teacher collaboration in instructional teams and student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 52 (3), 475-514.

Scholastic. (2015). Teachers seek to collaborate in and outside of school to best serve students. New York, NY: Author.

Sparks, S.D. (2018, February 6). A primer on continuous school improvement. Education Week.

Srinivasan, L. & Archer, J. (2018). From fragmentation to coherence: How more integrative ways of working could accelerate improvement and progress toward equity in education. New York, NY: Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Szczesiul, S.A. & Huizenga, J.L. (2015). Bridging structure and agency: Exploring the riddle of teacher leadership in teacher collaboration. Journal of School Leadership, 25 (2), 404.

Teach Plus. (2015). The decade-plus teaching career: How to retain effective teachers through teacher leadership. Boston, MA: Author.

Wiliam, D. (2014, September). The formative evaluation of teaching performance. East Melbourne, Victoria: Centre for Strategic Education.

York-Barr, J. & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarship. Review of Educational Research, 74 (3), 255-316.

Citation: Berry, B. (2019). Teacher leadership: Prospects and promises. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (7), 49-55.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Barnett Berry

BARNETT BERRY is a research professor at the University of South Carolina and co-leader of the Accelerator for Learning & Leadership for South Carolina .