Helping anxious students change their negative thinking patterns can reduce stress and improve their performance.

Anxiety is the most prevalent mental health disability affecting students across the United States. In fact, research suggests that almost a third of the country’s adolescents have struggled with an anxiety disorder during their childhood (Merikangas et al., 2010). However, few teachers receive significant training in their teacher preparation programs in mental health and behavioral best practices. By and large, teachers are left on their own to learn about the effects of anxiety on learning and behavior and to figure out how to address it in the classroom.

Persistent negative thoughts often lead to unproductive behaviors such as avoidance, defiance, and tearfulness.

Anxiety is characterized by rumination and negative or distracting thoughts as well as an increase in arousal and physiological symptoms (Vytal et al., 2012), and it is related to diminished performance across a wide range of school-related tasks (Moran, 2016). Negative thinking patterns — such as all-or-nothing thinking (“I don’t understand fractions. I stink at math!”) and catastrophic thinking (“If I fail my spelling test, I will never get into college!”) — can become intrusive and ongoing, taking a toll on a student’s mood, attention to tasks, working memory, and academic performance (Putwain, Connors, & Symes, 2010; Vytal et al., 2012). Such negative thinking disproportionately affects students with anxiety (Kertz, Stevens, & Klein, 2017; Rood et al., 2010). Further, persistent negative thoughts often lead to unproductive behaviors such as avoidance, defiance, and tearfulness (Leahy, 2002; Mahoney et al., 2016). For example, we’ve all known students who will shut down as soon as you give them an assignment. “I can’t do this” or “This is going to take forever,” they’ll tell themselves, then drop their head on their desk and close their eyes. Although we might be able to make some inferences about what might be happening in students’ minds based on these behaviors, thoughts are not observable, so it’s important to collect data on negative thinking via interviews or self-reporting and share that data with a psychologist to analyze (Berle et al., 2011; Mahoney et al., 2016) in order to monitor students’ thinking and the effectiveness of any intervention.

Most teachers are sympathetic by nature, but their intuitive efforts to help such students are often ineffective. Typically, for example, teachers may use incentives to encourage them (“Come on, buddy, if you get this done now, then you won’t have so much homework!” or “Recess is in 10 minutes. Let’s finish this so you can go outside”), and on occasion this may get the student to reengage. However, this sort of encouragement does nothing to silence the internal chatter of negative thinking, and the student is just as likely to shut down again the next time they receive a similar assignment. Clearly, other strategies would be more useful over the long term.

School counselors and psychologists certainly have a role to play in helping students who suffer from anxiety and negative thinking patterns — and they tend to be the only school personnel with specific training in how to address these issues. For example, some have expertise in the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), an evidence-based treatment for reducing negative thinking in anxious children (Muris et al., 2009). But it’s not realistic to send every anxious child to the counselor or psychologist, or to do so every time they seemed stressed out. The fact is that teachers come face-to-face with students’ anxieties every day; they are in a position to provide support, in addition to outside therapists and school counselors; and they can do so effectively if they understand certain basic principles and strategies.

Teachers can take proactive steps to check for stress and anxiety and head off negative thoughts before they begin to spiral out of control.

Change the perspective

Imagine checking in with a student at 3:00 to ask how the day went, and she says, “Horrible!” However, she seemed highly engaged and upbeat most of the time, and it’s hard to believe that her entire day was horrible. It’s more likely that she’s focusing so intently on the few negative moments she experienced that they eclipse everything else that occurred during the day, including many moments that were positive and others that were more or less neutral. These strategies tend to be particularly helpful:

Be specific

For example, when a student says her day was horrible, ask her to explain exactly what happened to make it such a bad day. She may describe a significant disappointment (“I failed my math test” or “I had a fight with my best friend”) or something more serious, in which case the teacher should validate her feelings (“I’m sorry that happened”) and walk the student to the counselor’s office for a check-in. The counselor may then contact the parent.

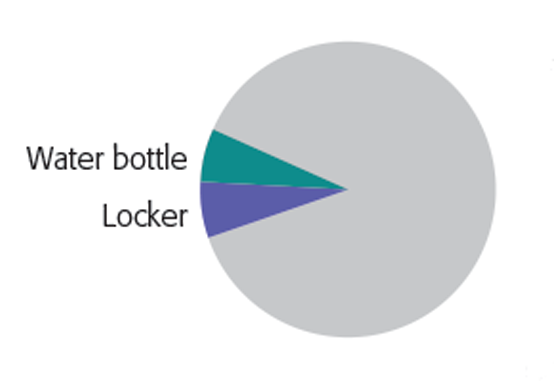

However, she may describe events that sound trivial (“I spilled my water bottle in homeroom, and I couldn’t open my locker”), which suggests that negative thinking has led her to blow them out of proportion. In that case, keep in mind that those events were significant to her, and be careful not to minimize her feelings. But also try to suggest a factual lens through which she can look at what happened: “It sounds like the first few minutes of the day were frustrating. How did the other six hours go?” The point here is to interrupt a negative thinking pattern (in this case, an all-or-nothing pattern, in which a couple of disappointing incidents have colored the entire day as “horrible”) by framing the events in a way that changes and limits their scale. It’s a coping strategy that the student can easily learn to use on her own, giving her a way to take a more balanced — and not so emotionally fraught and stressful — view of her experiences (Jordan, McGladdery, & Dyer, 2014).

Use visuals

Another way to help an anxious student gain a new perspective is to reframe it in visual terms. For example, when the student says that it was a horrible day because she spilled her water bottle and couldn’t open her locker, you can draw a circle to represent the entire school day, then draw these two negative events as a pair of slices in the day’s pie chart.

Again, without minimizing the student’s experience or devaluing her feelings, and after talking through the events and hearing out the student’s account, you can point to the two small slices and say, “I’m sorry those two upsetting things happened today.” The student can see for herself that the rest of the circle remains unmarked, visually representing the fact that most of the day went well.

Tell a different story

In addition to recasting negative events on a smaller scale, you may be able to get the student to change their perception of the story altogether, using a strategy called narration (Minahan & Rappaport, 2012). For example, imagine you have a student who tends to be anxious about fitting in at recess and often dwells on the negative moments (such as the minute he spent looking for somebody to play with) rather than the positives (such as the 15 minutes he spent playing, once he found a game to join). Steering him away from negative thoughts can be as simple as walking past and saying, “Wow, it looks like you two have been playing for 10 minutes straight.” Think of it as narrating a movie as you watch it: You’re not looking to converse with the student but, rather, to articulate the accurate facts of the situation so that the student notices and observes the positive information, too. Later in the day, he’ll think back on recess and remember the good as well (“I played with Nathan!”) rather than just dwell on the bad (“I couldn’t find anybody to play with”).

Be proactive

If students start the day or begin an assignment with a negative mind-set, they may never be able to get back on track and focus on their work. But teachers can take proactive steps to check for stress and anxiety and head off negative thoughts before they begin to spiral out of control.

Conduct regular check-ins

A formal check-in and check-out sheet can give you a quick read on how everybody’s feeling, while encouraging students to tell you right away if they’d like to talk about anything that’s bothering them. This gives you the opportunity to schedule a few minutes early on to touch base with the student, which may prevent them from ruminating on negative thoughts throughout the day. Similarly, you can post a wall chart that lists various levels of stress and anxiety. Students can start the day by putting a sticky note (with their name on the back) on the chart to indicate how they’re doing and/or privately request a check-in with a teacher or counselor (see, for example, the photo on page 29).

Give assignments that seem doable

The way in which you assign and introduce an academic task can do a lot to ward off anxieties and negative thoughts. For example, let’s say that your syllabus requires students to complete a complex social studies project, design and conduct a scientific experiment, or write an extended essay. If you simply ask a student to “get started,” he may become paralyzed by anxiety, imagining how difficult it will be to get through the whole assignment. But he’s likely to be much less overwhelmed if you ask him to tackle a discrete, manageable part of the larger project. By finding ways to break down the task into smaller (less intimidating) pieces, you can avoid triggering the negative thoughts that may cause students to shut down before they even begin. This can be as simple as telling the class, “As a first step in writing our essays, let’s see how far you get in 10 minutes, and then we’ll stop.” Or you can ask students to set a target for themselves — e.g., they can commit to writing for a specific number of minutes before putting down their pencil and taking a deep breath. And here, too, it can be helpful to provide a visual. For instance, you can post the first few sentences of an essay on the board, giving students a concrete reminder that beginning a writing project is a small step, and they don’t have to tackle the whole project all at once.

Provide evidence

Another effective way to help students reduce their negative thinking about an assignment is to show them empirical evidence that contradicts their anxious impresssions (Minahan & Schultz, 2014). For example, students will often say, “I stink at writing,” even if they’re quite competent and struggle with just a couple of skills, such as writing a good opening line or coming up with vivid examples. But it can be simple to gather and present them with data showing that their perceptions are inaccurate and helping them recognize their own pattern of all-or-nothing thinking. (For examples of the tools described below, see Minahan, 2014.)

Ask students to monitor their own progress

One useful way to show students evidence of their own competence and counter negative misperceptions is to ask them to monitor their own work. For example, if students will be writing an essay, give them a three-column self-monitoring chart to follow that includes a column listing various parts of the writing process to be completed (e.g., coming up with an idea, outlining the piece, writing an introduction, proofreading) and a middle column listing strategies that might help them if they struggle with any of these steps (e.g., looking at pictures in a magazine to get an idea for writing, looking back at a previously written paper to see how it’s organized). When students finish witing the essay, ask them to look at their chart and put check marks in the third column next to the strategies they actually needed to use. Typically, students will check no more than a few strategies, and you can point out that most parts of the writing project went smoothly. Over time, this sort of self-monitoring will help them understand that only some parts of the writing process tend to be challenging for them, and they can begin to replace anxious, all-or-nothing thoughts like “I stink at writing” with more specific (and manageable) ones like “I often have trouble thinking of an idea to write about.”

Ask students to rate their expectations and recollections

If you have particular students (or a whole class) who seem anxious about an assignment (i.e., once asked to start a task they immediately raise their hand and ask to go to the bathroom), ask them to begin by rating (on a scale of 1-5) how difficult they expect it to be. After they complete the assignment, ask them to rate it again on the same piece of paper in a second column so they can see the comparison. Repeat this without commenting or judging so there are five or more comparative “before/after” scores in one place. Most students will give the assignment a lower difficulty rating the second time, showing that it wasn’t as hard as they thought it would be. The next time those students become anxious about a project (shutting down emotionally, complaining that it’s too difficult, or practicing other forms of avoidance), show them the previous rating sheet, pointing out that the evidence contradicts their current perceptions about the difficulty of completing assignments. Help them internalize the lesson by asking them to explain why they rate assignments as less difficult in retrospect. Ideally, they’ll acknowledge that their first, anxious thoughts tend to be inaccurate.

This strategy can be also done with the whole class. You could ask the class to rate the difficulty of a test packet and then when they have completed it, ask them to rate it again. You can normalize this concept by asking kids if their number went down and why that might be — answers may include “My first thought is not accurate” or “I shouldn’t listen to my first thought.”

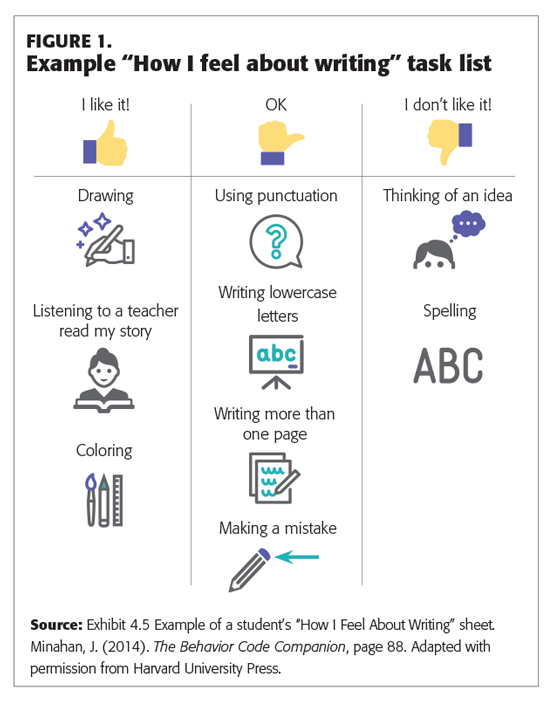

Similarly, give students a long list of discrete tasks that go into completing a stress-inducing activity — for writing an essay, for example, this might include sharpening a pencil, coming up with an idea, using punctuation, spelling words correctly, writing an introduction, and so on). Then have the student sort the small tasks into one of three columns based on their feelings about each part of the process: “I don’t like it,” “OK,” or “I like it.” The greater the number of tasks you put on the list, the more items students are likely to rate “OK” and “I like it.” (See Figure 1 for an example.)

The next time a student says, “I hate writing,” take out the sheet and encourage her to restate her comment: “Actually, you like most aspects of writing, but you don’t like spelling and thinking of an idea. Let’s review your strategies for those.” Over time, she may change her language to a more accurate statement such as, “I’m a good writer, but I have trouble with spelling.” Once she has a more accurate view of her own ability, she’ll be more likely to engage in the task because “writing” itself is no longer vilified.

This approach can also be used with the whole class and in a variety of subjects. For example, in the beginning of the school year, a middle school teacher can have students list out many parts of doing math (e.g., order of operations, addition, multiplication) and sort them into the “I like it,” “OK,” and “I don’t like it” columns. Later in the year, before introducing an algebra unit (where students’ anticipatory anxiety may be high), the teacher can have students refer to their self-rating sheets: “If you like order of operations, multiplication, or addition, you are going to like algebra, because that’s all it is!”

Small steps can make a big difference

Ideally, every anxious student would receive coordinated and ongoing support from a whole team of adults, including mental health providers, school counselors, teachers, and family members. But even on their own, teachers can take many small steps, using fairly simple classroom strategies, to help students tackle their negative thinking patterns. And the more they can do to help anxious students learn to recognize and reduce their negative thoughts, the more likely they are to see those students reduce their unproductive, avoidant, and defiant behaviors, allowing them to develop a more positive self-concept and engage in academic, social, and extracurricular activities to the best of their abilities.

Also by Jessica Minahan:

- Related: Building positive relationships with students struggling with mental health

- Related: The flexible classroom: Helping students with mental health challenges to thrive

References

Berle, D., Starcevic, V., Moses, K., Hannan, A., Milicevic, D., & Sammut, P. (2011). Preliminary validation of an ultra brief version of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18 (4), 339-346.

Jordan, J., McGladdery, G., & Dyer, K. (2014). Dyslexia in higher education: Implications for maths anxiety, statistics anxiety and psychological well-being. Dyslexia, 20 (3), 225-240.

Kertz, S.J., Stevens, K.T., & Klein, K.P. (2017). The association between attention control, anxiety, and depression: The indirect effects of repetitive negative thinking and mood recovery. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping: An International Journal, 30 (4), 456-468.

Leahy, R.L. (2002). Improving homework compliance in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58 (5), 499-511.

Mahoney, A.E.J., Hobbs, M.J., Newby, J.M., Williams, A.D., Sunderland, M., & Andrews, G. (2016). The Worry Behaviors Inventory: Assessing the behavioral avoidance associated with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 256-264.

Merikangas, K.R., He, J.-P., Burnstein, M., Swanson, S., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., . . . Swendsden, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity study-adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49 (10), 980-989.

Minahan, J. (2014). The behavior code companion: Strategies, tools, and interventions for supporting students with anxiety-related or oppositional behaviors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Minahan, J. & Rappaport, N. (2012). The behavior code: A practical guide to understanding and teaching the most challenging students. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Minahan, J. & Schultz, J. (2014). Interventions can salve unseen anxiety barriers. Phi Delta Kappan, 96 (4), 46-50.

Moran, T.P. (2016). Anxiety and working memory capacity: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 142 (8), 831-864.

Muris, P., Mayer, B., den Adel, M., Roos, T., & van Wamelen, J. (2009). Predictors of change following cognitive-behavioral treatment of children with anxiety problems: A preliminary investigation on negative automatic thoughts and anxiety control. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 40 (1), 139-151.

Putwain, D.W., Connors, L., & Symes, W. (2010). Do cognitive distortions mediate the test anxiety-examination performance relationship? Educational Psychology, 30 (1), 11-26.

Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bögels, S.M., & Alloy, L.B. (2010). Dimensions of negative thinking and the relations with symptoms of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34 (4), 333-342.

Vytal, K., Cornwell, B., Arkin, N., & Grillon, C. (2012). Describing the interplay between anxiety and cognition: From impaired performance under low cognitive load to reduced anxiety under high load. Psychophysiology, 49 (6), 842-852.

Citation: Minahan, J. (2019, Oct. 28). Tackling negative thinking in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, 101 (3), 26-31.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jessica Minahan

Jessica Minahan is a licensed and board-certified behavior analyst, special educator, and consultant to schools internationally. She is the co-author of The Behavior Code: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Teaching the Most Challenging Students and author of The Behavior Code Companion: Strategies, Tools, and Interventions for Supporting Students with Anxiety-Related or Oppositional Behaviors.