Now that conflicts over Common Core have eased up, it’s easier to take stock: While Common Core advocates badly lost the political battle on social media sites like Twitter, they won the policy war. And the rules of political advocacy in education will never be the same again.

My colleagues Alan Daly, Miguel del Fresno, Christian Kolouch, and I have been tracking the Common Core debate on Twitter since 2013, and we recently released our findings on an interactive and publicly accessible web site (www.hashtagcommoncore.com) that illuminates how this social media platform is influencing education politics and policy.

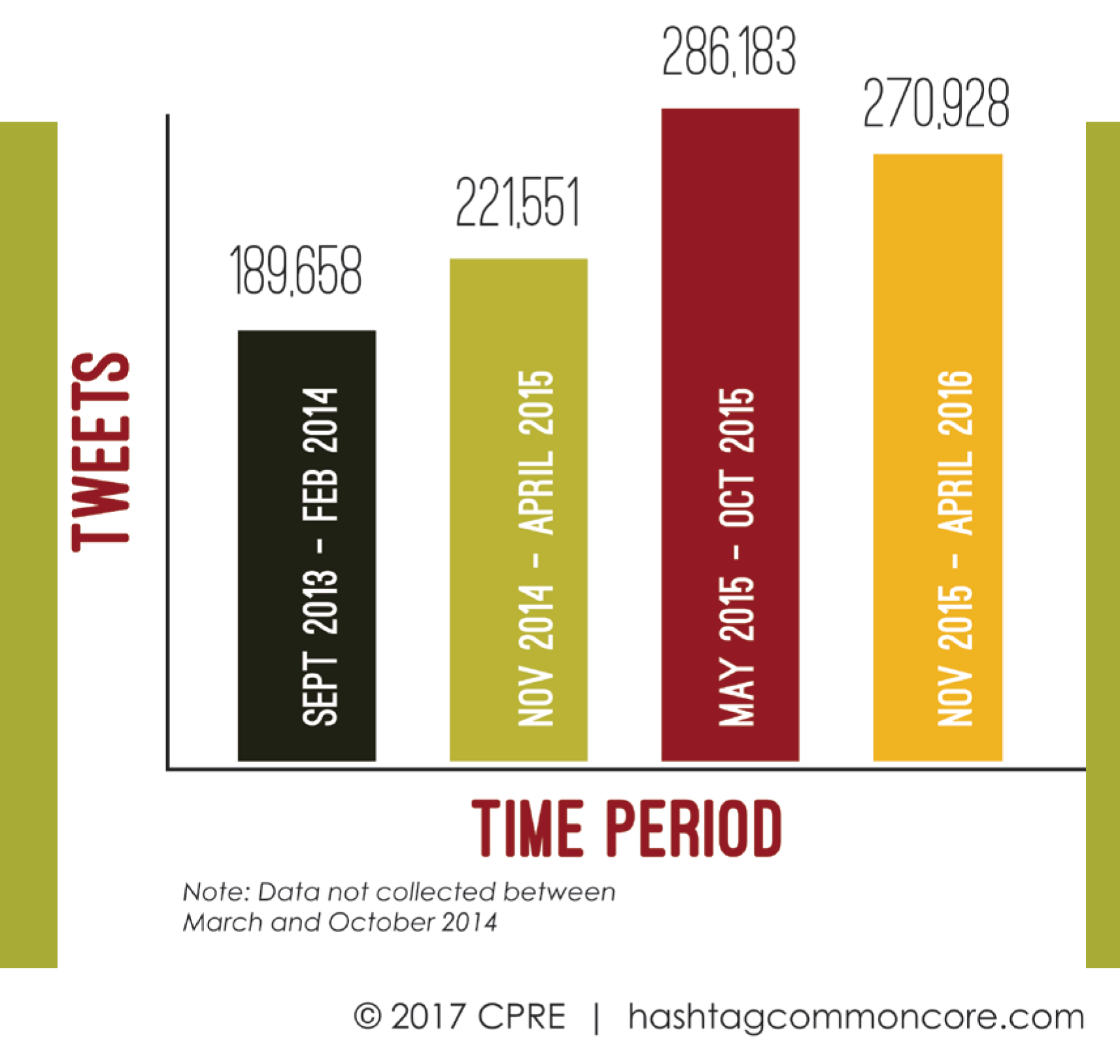

In our investigation, we examined nearly one million tweets from about 190,000 distinct authors between September 2013 and April 2016. This covered the key time period in which public support for the standards declined and became increasingly polarized along political party lines. Our investigations combined social network, psychological, and discourse analyses to examine the political debate surrounding Common Core as it played out on Twitter.

We found that activity increased each year from 2013 to 2016. Using social network analytical techniques, which connect people based on their behavioral choices, we identified three major communities or factions in the Twitter debate surrounding Common Core:

- Supporters of Common Core,

- Opponents of the standards from inside education, and

- Opponents from outside education.

Our initial analyses — from September 2013 through February 2014 — revealed fairly equal participation among the three factions. Two years later, though, opponents from outside education accounted for more than 75% of the activity, while Common Core supporters had dwindled to less than 10%, and Common Core opponents from within education made up the remaining 15%.

During the Common Core debates, Twitter was a robust terrain for grassroots activists rather than one dominated by professional advocacy groups.

As we disentangled the giant social network, we noted that most participants were casual contributors: Almost 95% of them made fewer than 10 tweets in any given six-month period. We focused our attention on the actors with the highest influence in the social network. We distinguished between two types of influence on Twitter:

- Transmitters, those who tweeted a lot, regardless of the extent of their followership; and

- Transceivers, those who gained their influence by being frequently retweeted and mentioned by others.

Over time, we found that participants from outside education were increasingly dominant in both the transmitter and transceiver networks.

We were also surprised to find that Twitter was a robust terrain for grassroots activists rather than one dominated by professional advocacy groups. While traditional advocacy groups certainly developed a footprint on Twitter, the most fervent activists tended to be motivated and concerned citizens who are consistently active on Twitter and who believe this medium is the best way to express themselves and be heard amid the national clamor.

The principle of local autonomy drowned out discussion about the quality of the standards.

When we looked at the ebbs and flows of the Twitter conversation, we identified specific issues driving the major spikes in activity. Some of the action was based on very real events, such as the time, in November 2013, when Secretary of Education Arne Duncan spoke about white suburban moms’ opposition to Common Core, or in November 2015 when Congress debated the Every Student Succeeds Act. But we also saw evidence of manufactured controversies spurred by efforts to sensationalize minor issues, as well as several examples of outright fake news stories (such as a children’s book on an authorized Common Core reading list that was distorted to claim that President Barack Obama was the Messiah, and a conflict resolution activity that was misrepresented to claim that students were being indoctrinated to become anti-Israeli and to “divide Jerusalem”).

It is important to note, however, that politics (efforts to shape opinions, beliefs, and decision making) and policy making are two different things. While public sentiment and political pressure caused many states to rethink their support of the standards, few of them had the capacity to create new and better standards of their own — nor did Common Core opponents develop plausible alternatives. Thus, to alleviate the political pressure, many states that had initially adopted Common Core simply renamed, repackaged, and reinstituted it (McGuinn & Supovitz, 2016; Layton, 2014). Polls continue to show that the Common Core standards are drawing less public support, and views are increasingly divided along partisan lines, but the substance of Common Core is well-entrenched in American education.

Common Core as a proxy

In a sense, the controversy over Common Core was never really about the standards themselves. As our analysis of the Common Core debate on Twitter shows, the dispute about the standards was largely a proxy war over other politically charged issues, animated by:

- Opposition to the federal role in education, which many believe should be the domain of state and local educators;

- Fears that Common Core could become a gateway for access to data on children that might be used for exploitive purposes rather than to inform educational improvement;

- Opposition to the continued proliferation of testing;

- Fears that business interests will exploit public education for private gain; and

- A belief that an emphasis on standards reform distracts from the deeper underlying causes of low educational performance, which include poverty and social inequity.

What Common Core opposition did accomplish was to push back against forces that sought to centralize and cohere America’s education system. Progressive reformers wagered that, based on evidence from international comparisons, common standards and national assessments that reach across state and locally developed systems would produce a more effective and equitable education system. The very design of the Common Core movement, framed as a state-led effort to adopt common standards and common assessments, was an effort to thread the needle of local control nested within a centrally orchestrated system in a nation where people are fundamentally committed to local control. If anything, this experience shows that the deep-seated belief in state-led and locally based education systems, which draw their strength from America’s profound historical distrust of centralized power, are entrenched in our national ethos. The principle of local autonomy drowned out discussion about the quality of the standards themselves.

Analyzing the dispute about the standards as it played out in a variety of public forums and state capitals — and particularly through the prism of Twitter — reveals several insights into the changing dynamics of how political debates occur in America.

Like other democratic arenas, education policy is crafted within a political environment of competing interest groups seeking to dominate the issue and foster public pressure to advance their views. The dynamics of educational advocacy have fundamentally changed in three ways.

#1. Information dissemination is undergoing a dramatic transformation.

Common Core was the first major education policy reform in the social media age. The previous major reform to command national attention, No Child Left Behind, was signed into law in 2002 before the first Like on Facebook (2004), before the first video upload on YouTube (2005), and before the first tweet on Twitter (2006).

Comparing the media environment of the NCLB decade and the Common Core era is illustrative. During the implementation of NCLB, the professional media was increasingly splintered. Cable TV gave rise to news channels with both conservative (i.e. Fox News) and liberal (i.e. MSNBC) slants that courted different audiences. Reporting of events increasingly blended with the opinions of pundits and surrogates. In this raucous environment, it became more and more difficult to discern which were the mainstream media outlets. Once unquestioned and authoritative news sources like the New York Times, Washington Post, and CNN stood along an increasingly disparate continuum of news sources. Yet, even as this splintering occurred, professional media were still regarded as the “official” sources of information for Americans.

Social media has changed the landscape in at least two profound ways. First, stories that become “news” are increasingly introduced into the public’s consciousness through unfettered and unverified alternative sources via the internet and social media. Organizations and individuals can directly and widely disseminate information unvetted by formal sources. This loosening of the hold of the professional media on information has led to broader reporting of activity and events but also has the effect of increasing unsubstantiated, exaggerated, and even outright fake news stories. In our investigations of Common Core on Twitter, for example, we identified several online “news” organizations like Investors Business Daily and WorldNetDaily, which used the legitimacy of appearing as news sites to overtly push a particular ideological slant. For better and worse, the spigot has opened wider, and what comes out is largely unfiltered.

Second, newsmakers no longer need to rely solely on the professional media to communicate broadly to people. Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms offer ways for public figures to speak directly to citizens without going through the media middleman. This diminishes the power of the professional media because they no longer have a monopoly on access to the public, but this change also means the media and public have more difficulty holding public figures accountable for their messages.

#2. Fueled by technology, advocacy groups are becoming increasingly powerful.

Our analyses uncovered a number of ingenious strategies in the Common Core kerfuffle on Twitter. Canny and tech savvy, these partisan strategies demonstrate the growing sophistication of issue advocates as they learn how to capitalize on the social and technological power of networking mediums. These strategies help explain how the opponents of the standards were able to dominate the political conversation and influence public opinion.

Amplifying the message. The Patriot Journalist Network is a loosely affiliated group of committed grassroots Twitter activists advocating conservative causes. PJNET activists used a range of effective tactics that helped them increasingly dominate the Twitter conversation about Common Core. Most inventive was PJNET’s use of a robo-tweeting technology that let them send messages from the accounts of consenting Twitter users. This essentially created a network, which we dubbed a “BotNet,” which integrates robo-tweeting and social networks.

What makes this approach so powerful is that it both dramatically increases the volume of the same message and makes it appear that the message is being sent independently by multiple users when it is really a concerted effort of amplification. PJNET also used clever forms of retweeting and hashtag rallies to bring advocates together to amplify their message. By using these strategies to harness the people power of social networks on Twitter into concerted issue campaigns, they demonstrated how powerful these efforts can be and how they can create enough synergy to bust out of Twitter and into the broader consciousness.

Common Core opponents framed the standards as a threat to children and appealed to the value systems of a diverse set of constituencies.

Framing issues to shape attitudes and public perceptions. Common Core opponents framed the standards as a threat to children and used a range of metaphors to appeal to the value systems of a diverse set of constituencies. We identified five different frames:

- Government Frame, which represented the standards as an oppressive government intrusion into the lives of citizens, thereby appealing to limited-government conservatives;

- Propaganda Frame, which depicted Common Core as brainwashing children, which hearkened back to the Cold War era when social conservatives positioned themselves as defenders of the national ethic;

- War Frame, which portrayed the standards as a front in the nation’s culture wars and which appealed to social and religious conservatives to protect traditional cultural values;

- Business Frame, which rendered the standards as an opportunity for business interests to profit from public education, a frame that appealed to liberal opponents of a business exploitation of a social good; and

- Experiment Frame, which used the metaphor of the standards as an experiment on our children, therefore appealing to the principle of care that is highly valued by social liberals.

Collectively, these frames, and the metaphors and language that triggered them, appealed to values of both conservatives and liberals and contributed to the broad coalition, from both inside and outside education, to oppose the standards.

Used in combination, the internet and social networks are powerful tools with which interest groups can influence public opinion. We see evidence that both the messages and the messaging system are becoming more sophisticated, with Twitter serving as an organizing force to bring people together into a grassroots multi-issue influence engine.

#3. The audiences that consume “content” are becoming increasingly segmented.

One consequence of the technology-enhanced customization of information sources and the increased sophistication of advocacy strategists is that they offer people both comfortable enclaves and easily consumable materials that reinforce their prior beliefs and protect them from discordant views. It is not surprising that people want information that validates and corroborates their prevailing perspective. Sociologists use the word homophily to describe the natural phenomenon that individuals prefer to associate with those who hold similar preferences and worldviews to their own. In other words, people naturally gravitate toward those who hold similar views and, in a world of choice, we are attracted to information sources that are popular with the people with whom we are most comfortable interacting.

The splintering of the professional media and talk radio accelerated the fragmentation of society into increasingly homophilous groups. But the internet and social media have exacerbated this phenomenon so that most of us interact with and get the bulk of our information from people who share similar belief systems. This fragmentation into homogeneous subgroups, which continually reinforces members’ belief systems, is a sort of voluntary social segregation.

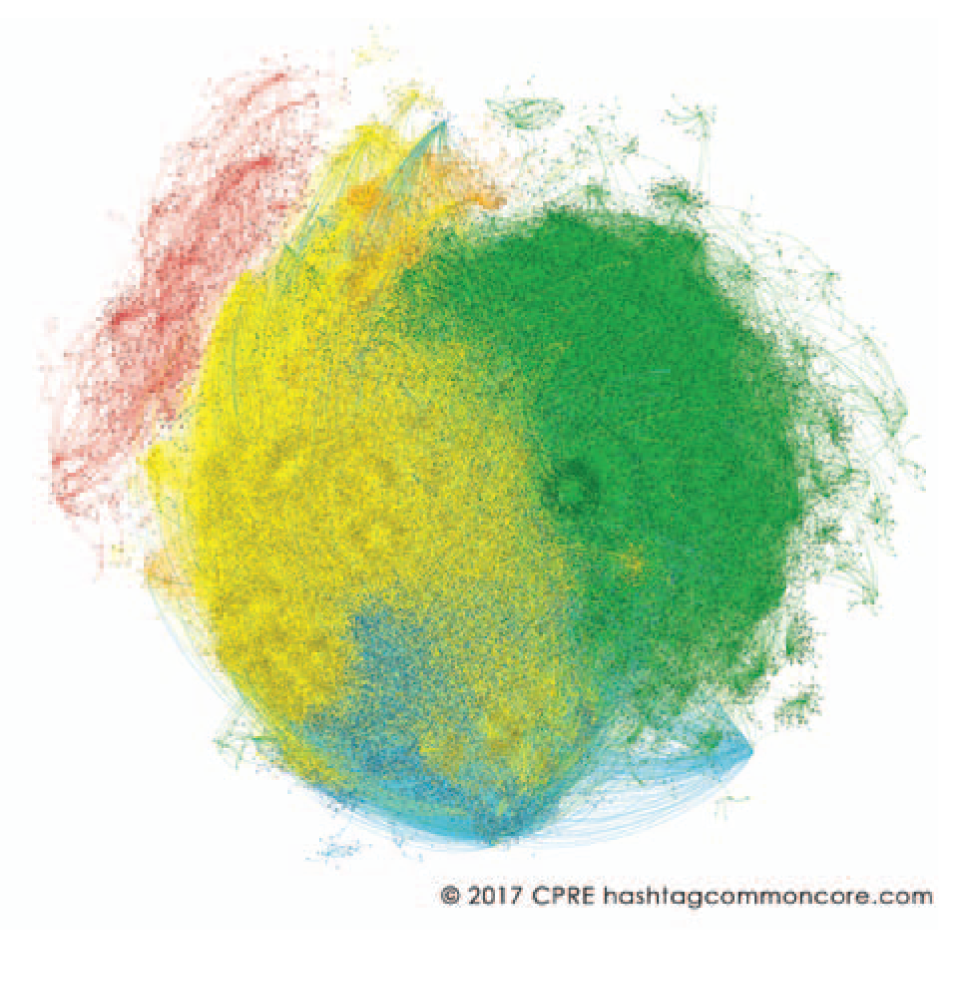

We saw this same phenomenon at work in communities that formed during the Common Core debate on Twitter. As you can see in the network image above of about 55,000 participants from November 2014 to April 2015, the behavioral activity of Twitter participants (in terms of whom to follow, retweet, and mention) revealed that people tended to interact far more with those who held similar views than with those from different factions.

What are the implications of this naturally occurring phenomenon of people dividing themselves in this way? First, in our increasingly digital age, physical proximity may be playing a less and less important role in our political debates about education. It is telling to note that the PJNET team of synchronized actors interact completely in virtual space and have never met each other in person (Prasek, 2017).

Second, and perhaps most important, the fragmentation of people’s personal, political, and cultural experiences gives us fewer opportunities to share common experiences or to be exposed to (and come to understand) views and beliefs that differ from our own. In fact, abundant research shows that people who only interact with those who share similar views become more polarized in their perspectives, regardless of whether they are liberal or conservative, than those who have opportunities to hear alternative perspectives (Schkade, Sunstein, & Hastie, 2007; Gastil, 2008; Flaxman, Goel, & Rao, 2013).

Conclusion

So let’s string together these three observations: First, how information is produced and made public is undergoing a dramatic transformation; the volume and diversity of information sources are expanding, and consequently the quality and veracity of information is suffering. Second, the missives and dissemination tools of the messengers are becoming more sophisticated as they capitalize on psychological influence techniques and better use social networks to ripple messages outward. And third, the audiences that consume content are becoming increasingly segmented. This seems to promise only the further rending of the social fabric.

In this environment, we must ask what institutions create the shared experiences that hold us together as a nation. Politics might be one, but as we increasingly see, the information we get about politics, which shapes our views about candidates and issues, is not shared. Popular culture might be another source of unity, but we’re becoming less and less likely to have the same cultural experiences. Perhaps major sporting events still bring us together — Super Bowl viewership is certainly large, and people feel a sense of national pride when the U.S. Olympic team takes the field. Jury duty is another of the few remaining civic duties where one is put in a position to engage with a cross-section of different people from society for a common purpose.

And then there are public schools, which nine out of every 10 students in the country attend. Indeed, public education may be one of the last remaining bulwarks against the disintegration of the body politic. No wonder Common Core was such a contentious issue.

References

Flaxman, S., Goel, S., & Rao, J.M. (2013). Ideological segregation and the effects of social media on news consumption. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2363701. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

Gastil, J. (2008). Political communication and deliberation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Layton, L. (2014, Jan. 30). Some states rebrand controversial Common Core education standards. Washington Post.

McGuinn, P. & Supovitz, J. (2016). Parallel play in the education sandbox. Washington, DC: New America Foundation.

Prasek, M. (2017, January 4). Personal communication.

Schkade, D., Sunstein, C.R., & Hastie, R. (2007). What happened on deliberation day? California Law Review, 915-940.

Citation: Supovitz, J. (2017). Social media is the new player in the politics of education. Phi Delta Kappan 99 (3), 50-55.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jonathan Supovitz

JONATHAN SUPOVITZ is a professor of policy and leadership in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania and codirector of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education, Philadelphia, Pa.