A new documentary raises questions about an over-simplified discussion of racial integration and highlights the need to focus on white students and families in examinations of racial inequality.

By Alexander Russo

One of the big coverage trends in education journalism for the past several years has been the ills of racially segregated schools and efforts to integrate them.

Explicit and otherwise, the argument usually made by those who write these pieces is that integrating schools would provide substantial educational improvements.

The inequity of the current system is in little doubt, warranting all the attention it has received and then some. This week’s New York Times/ProPublica look at inequality in Charlottesville, VA, schools is a timely example.

But what if integrating schools isn’t as clear or unequivocal a solution to educational inequality as it may appear?

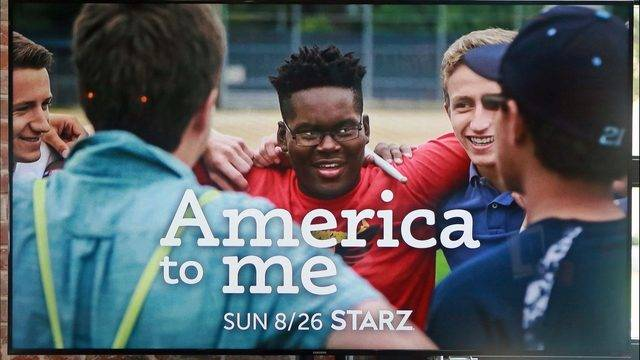

That’s the central question raised in the documentary series “America to Me.”

As you will see, integration has proven to be far from an unmitigated benefit at Oak Park-River Forest High School, an ostensibly integrated high school located in a much-admired progressive community just outside Chicago.

“Just because you’re putting everybody in the same school and giving them the same opportunity doesn’t make everything equitable,” notes Kevin Shaw, one of the filmmakers behind the series. Far from it.

The depiction of these challenges also suggests that journalists who write about inequality and integration may need to deepen their work to address a much more complicated reality.

I’m not arguing that the kids of color at Oak Park are doing objectively worse than they would have at a segregated school, or that racial inequalities and school integration aren’t topics worth reporting.

I’m just saying that reporters need to avoid assumptions that may lead them (and their readers) away from a deeper understanding of what’s needed.

One of the Oak Park River Forest students negotiating different groups and expectations at the school

The past few years have seen a noticeable surge in education journalism about school segregation and efforts to ameliorate racial inequalities.

The most obvious example is Nikole Hannah-Jones’ writing for the New York Times magazine and ProPublica and producing for This American Life. The MacArthur “genius” award winner is currently working on a book on the topic. See a collection of her work here.

But there are many more examples, including the award-winning Baltimore Sun series “Bridging the Divide” by Liz Bowie and Erica Green, Lauren Camera’s US News series on district secession efforts, the Hartford Courant’s admirable series, and Alvin Chang’s Vox piece “School segregation didn’t go away.”

These are all important, well-written pieces that deserve the attention that they received.

The argument for school integration holds that kids of color do better when they attend schools that aren’t racially isolated and that white kids are not negatively affected.

The presence of a mix of different students is believed to benefit all children in terms of their future working lives in a diverse society, and help improve social cohesiveness in America.

Hannah-Jones in particular notes the reductions in achievement gaps that took place at roughly the same time as desegregation efforts were at their most robust.

She also declared that education journalists weren’t doing their jobs if they weren’t writing about school segregation, and described white journalists as being complicit in perpetuating segregation.

There may be some truth to that, but there have also always been questions about the school integration argument, or at least about school integration on its own with no further attention paid to how students of color are treated at those integrated schools.

“It’s a very slippery slope to simply say, ‘Integration worked before and so now we need to do it again,’” New York University professor R. L’Heureux Lewis-McCoy said in a recent phone interview. Author of the book Inequality in the Promised Land: Race, Resources, and Suburban Schooling, Lewis-McCoy says that school integration is “not as simple as people posit it is.”

“America to Me” is just the most recent – and perhaps the most powerful – depiction of the complexities that are involved.

Related: An interview with Kevin Shaw about the making of the series

https://youtu.be/-uNhmWJ4l5k

Episode eight of the series aired last weekend. Episode nine airs on Sunday. You can read recaps of each episode at Chicago magazine. There are some great supplementary interviews with Oak Park teachers at The Hollywood Reporter.

The series on Oak Park presents a sharp challenge to anyone who may be tempted to think that integration is a panacea.

Looked at from the outside, the school seems like a success story. The student population includes a mix of different races. Overall achievement levels are high, as is the rate of students attending college. The well-resourced school features a slew of clubs and activities, including a strong wrestling squad and a powerhouse spoken-word poetry team. The school is run by a relatively young African-American principal and staffed by what seems to be a strong mix of faculty.

However, the injustices experienced by students and teachers of color during the series are so plentiful, it’s hard to keep track of them all.

The achievement gap between white and nonwhite students is large and persistent – having grown over the past 15 years despite repeated attempts and promises for improvement. White students dominate the advanced courses. Nonwhite students are over-represented in the general track and in disciplinary infractions.

An African-American assistant principal feels that school leadership isn’t paying enough attention to racial inequality and isn’t empowering her work. She leaves for another job shortly into the series. A charismatic biracial English teacher who’s researched an intervention that could help reduce the achievement gap is thwarted. Since the series completed, she has also now left the school.

The parent of an African-American student with disabilities has to exhort teachers to put her son in more challenging classes and imply the threat of legal action to persuade administrators to give her son a 1:1 aide, something that white students in his situation are given.

A black AP history teacher notices white parents trying to transfer their children out of his sections before they’ve even taken his class, based purely on seeing the name “Tyrone Williams” in the course listing. (The department head says he rebuffs these requests as a form of “white flight.”)

Black students describe being followed home by school district investigators based on the suspicion they don’t live close enough to be eligible to attend the school.

To me, at least, the message is clear. Sending kids from different backgrounds to the same school buildings may help some kids in some ways. But it’s the very beginning of the process, not the destination.

One of the handful of white students whose experiences are included in the second half of the series.

So what should education journalists do?

The answer isn’t avoiding the topic of racial inequality, as sensitive and complicated as it is. Journalists need to keep focusing their attention on these widespread, persistent injustices that are taking place in our schools.

What will help is making sure that stories about integration and segregation aren’t simplistic or superficial. That’s what makes “America to Me” so powerful: it depicts all the ins and outs of an integrated school, rather than assuming or oversimplifying.

Among other things, that means education journalists should:

*Question the assumptions behind school integration efforts. Uncomfortable as it may be, ask how integration will address the issues and what additional programs and supports are being provided?

A small group of journalists and advocates of color have raised questions about the challenges and tradeoffs involved in school integration. In addition to Lewis-McCoy, they include the New York Times’ Farah Stockman (who won a Pulitzer for her series re-examining Boston’s effort to integrate schools), Malcolm Gladwell (who has examined the unintended effects of the Brown v. Board of Education decision), Rishawn Biddle, Chris Stewart, and Howard Fuller.

“Integrating the schools is not enough,” says Shaw, who is already working on another education documentary. “There needs to be some true equity work that’s done to meet the needs of all the students who are there.”

*Explore the successes and challenges of integrated schools. The vast majority of segregation coverage focuses on under-resourced schools in urban communities of color that are trying to diversify. Find integrated schools that exist and explore how well they do (or don’t) improve matters.

Two books depict integrated school systems where racial inequalities have remained a stubborn problem include Amanda Lewis and John Diamond’s “Despite the Best Intentions: How Racial Inequality Thrives in Good Schools” and Lewis-McCoy’s “Inequality in the Promised Land.”

*Be sure not to leave the white kids and families out of the picture. This is perhaps the most important lesson for education journalists from the series, and one of the most challenging.

The obstacles to focusing more attention on structural issues and white privilege are many. The people who enjoy privilege rarely want to be made uncomfortable, much less held accountable. And those of us who are white may feel uncomfortable questioning those who look like ourselves.

But there’s really no other way to do the job right.

“America to Me” isn’t a perfect example of how to depict school integration.

In a review of the first three episodes, Lewis-McCoy noted a glaring absence of “the voices and experiences of white students and families who accrue the spoils of suburbia whether traversing town or selecting advanced placement courses.”

Indeed, “America to Me” filmmaker Steve James urges education journalists to do better than he did on this score. In a phone interview earlier this week, James said that he learned the hard way that “you can’t really tell the story of how the system doesn’t work for black and biracial kids without looking at how it works for white kids.” There are significant moments with white kids in the second half of the series, James notes, but “we could have done more.”

However, the series is one of the rare pieces of journalism that makes a real effort to examine the white privilege and power that underly the school’s structural inequality. “Pound for pound, ‘America to Me’ does this better than most education documentaries,” says Lewis-McCoy.

And so, if you’re a reporter looking to write about integration or issues related to racial inequality, part of your research should be watching the series. Doing so will help deepen your understanding and improve your journalism.

Previous columns:

Some Questions About This American Life’s School Integration Story (2015)

Three Key Moments In The Hartford Integration Episode Of “This American Life” (2015)

Strong Start for Baltimore Sun’s Segregation Series (March 2017)

Nikole Hannah-Jones, the Beyoncé of journalism (2017)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/