The predominant model for teaching history lacks coherence and is built on incorrect assumptions about what young children are able to learn.

For decades, education writers have commented on the need to revamp the preK-12 history curriculum, especially at the elementary level (e.g., Akenson, 1987; Brophy & Alleman, 2006; Wade, 2002) During this time, the expanding horizons (EH) curriculum has continued to persist as the dominant model for history curricula.

Formerly called expanding environments, EH has been recognized as the major organizing idea for the elementary social studies curriculum since the late 1930s (LeRiche, 1987). Originating alongside the concept of social studies, this framework changed historical curricula so that instead of following a chronological approach, they follow a student-centered approach. Curricula adhering to the EH framework start with students’ everyday experiences and slowly expand out to examine their local area, their state, the larger country, and lastly, the world. The basic idea is that the child’s understanding develops through a consistently widening set of concentric circles. This gradually expanding horizon of students’ learning was quickly accepted as logical by many educators. The EH framework is not logical, however, if you wish to see students increase their historical knowledge and skill.

The prevalence of the EH model

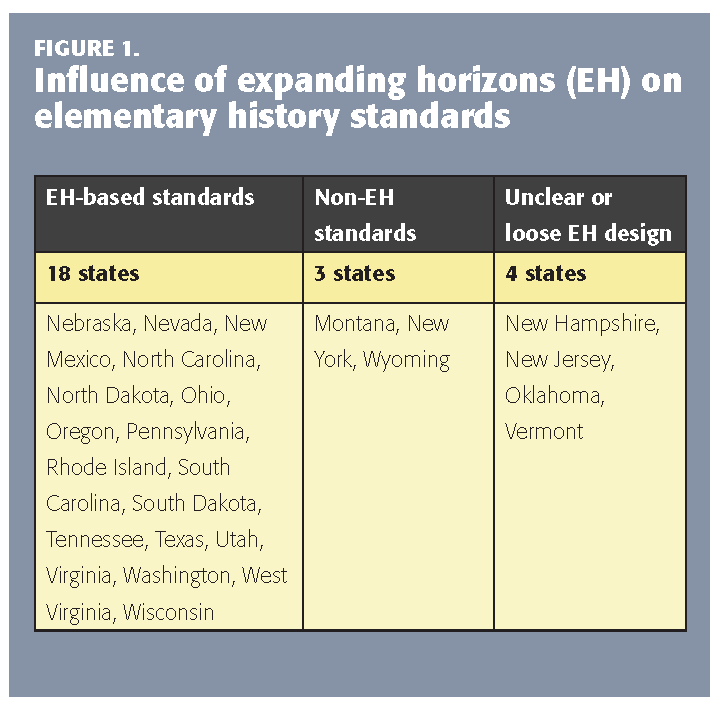

A brief review of current history standards of 25 U.S. states (those in the latter half, alphabetically) reveals that 18 of the 25 have standards that adhere to the EH framework. Of the seven that do not clearly ground their standards in the EH model, four appear to have loose connections to EH in history and clearer EH influence in other areas of the social studies. Figure 1 presents a breakdown of these results, illustrating the continued, widespread influence of EH.

Despite criticism, the approach has persisted. James Akenson (1987) offered a critique of the EH approach in elementary education but was pessimistic about its ever changing due to the economies of scale and conditioning of educators. About a decade later, Rahima Wade (2002) made another significant critique of the EH framework, noting that it is deeply entrenched in current systems.

Standards built on the EH framework follow a spiral pattern outward beginning with the learner at its center. For example, in South Carolina, the current draft of the kindergarten Social Studies College- and Career-Ready Standards focus on “The Community Around Us,” the 1st-grade standards move outward to “Life in South Carolina,” the 2nd-grade standards emphasize “Life in the United States,” and so on (S.C. Department of Education, 2018). Typically, the student learns about history through looking at his or her personal past, or topics that are classroom-bound, before expanding to the community, the state, the country, and finally the world. This pattern of consistently expanding “horizons” to explore historical content is where the model gets its name.

The model is inspired by John Dewey’s ideas about the need for curricula to be relevant to students. Dewey (1916) acknowledged the importance of history education in one respect, stating that “a knowledge of the past and its heritage is of great significance when it enters into the present . . . but not otherwise” (p. 88), he adds, dismissing the importance of history itself.

Decades later, Dewey’s argument — that history is only worth studying if it’s obviously relevant to the present — had morphed into a prevailing belief among history educators that content is little more than a means to an end (Becker, 1965). And, indeed, a major appeal of the EH framework is its emphasis on things that are of more immediate personal connection to learners than the more distant and abstract content of history, which may be of little interest to students. However, this contempt for the specific details of history, unless it has immediate relevance to today, is important in understanding significant defects of the EH framework. The widespread and long-lasting influence of the EH curriculum on history education has, as E.D. Hirsch (2017) explains, resulted in “a fragmented elementary curriculum with unpredictable topics being studied in different classrooms at the same grade level within the same school. Knowledge is not built up systematically” (p. 63).

The illusion of logic in the EH approach

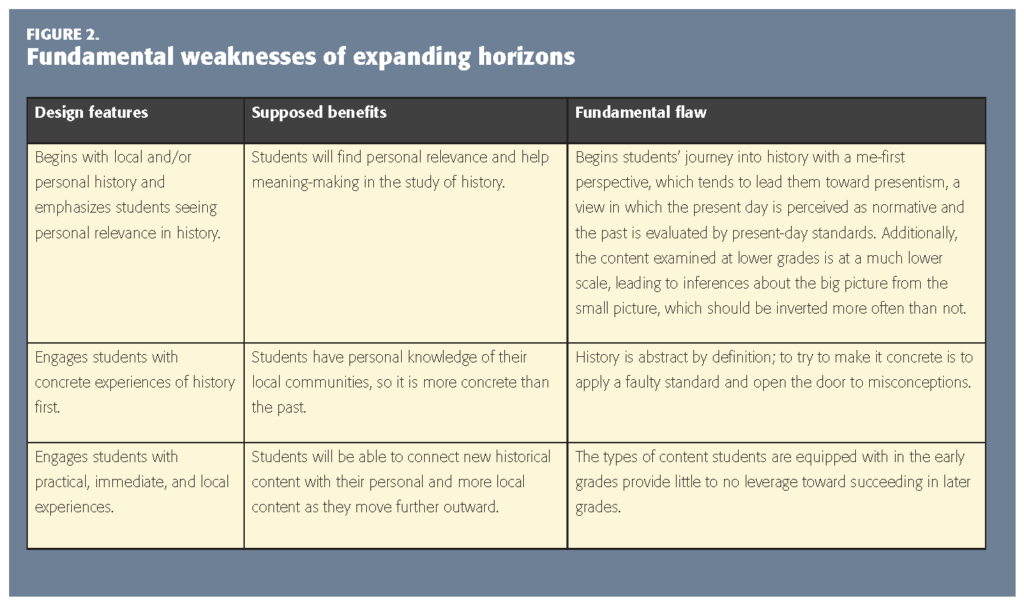

While the EH pattern proceeds in a way that might seem logical, it fails to equip learners with information that has any real bearing on their future learning, and it often focuses on content that is as trivial and inconsequential as it is “personally relevant”; consequently, any “logic” to its design is illusory. When we examine the design of EH, we find that the connections between the curriculum and students’ lives are mostly superficial and tend to put students on a faulty path toward historical understanding. (Figure 2 lists the supposed benefits of various features of the EH model along with the ways these features might hinder students’ development as historical thinkers.)

Below, I describe three of the model’s major flaws. Each of these is built on ideas that some may take to be laudable — but as is often noted, the pathway to hell is paved with the best of intentions. These premises sound appealing in the abstract, but the question is to what extent do they actually lead to the development of students’ knowledge and skill? By this measure, EH fails to pass the test and results in a curriculum that is incoherent and infantilizing.

Age-appropriate assumptions

The EH framework is largely derived out of John Dewey’s calls to make the curriculum more useful and user-friendly. As such, it is loaded with assumptions about what is useful and for whom. This, in particular, has catastrophic ramifications for younger students. In the EH framework, the elementary grades are filled with learning experiences that are completely trivial and largely a waste of time in that they provide little benefit to improving student learning in the future. Guided by the EH approach and its emphasis on being student centered, students in elementary grades are engaged frequently in intellectually vapid activities (Fischer, 2011) where they each share their uninformed perspectives on historical ideas insofar as they connect to themselves. Or, each student is asked to take history and always put it into his or her own experiences. In instances such as these, because they fit in with widely held views about what is “age appropriate,” they persist, in spite of the fact that these views about age appropriateness are mistaken, and these lessons do not provide leverage for later learning.

Much of the support for the EH framework is derived from the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s influential theories about human development, which hold that young children are unable to grasp abstract ideas or concepts beyond their immediate experience. But Piaget’s work is hardly the sound foundation that many assume. More than three decades ago, Leo LeRiche (1987) noted that it was incredible to see the expanding environments curriculum ascend to such dominance in spite of the fact that it was based on an obsolete 19th-century theory of child development. More recently, Kieran Egan (2005) noted that even though much of Piaget’s developmental theories — particularly the assumption that young children can’t learn things beyond their immediate experience — have been discredited, his theory remains almost an article of faith among many educators.

The failure to dismantle these widely held assumptions has meant, as Felipe Fernandez-Armesto (1997) put it, that “generations of schoolchildren [have been] deprived of challenging tasks because Piaget said they were incapable of them” (p. 18). In fact, argues E.D. Hirsch (2017), “By kindergarten, what makes a topic inappropriate for children is not their stage of development but the state of their relevant knowledge” (p. 66). Yet, many elementary-level teachers continue to denigrate the intellectual capacity of their students, choosing not to engage them in meaningful history instruction.

Radical individualization

Another curricular flaw of the EH model is its assumption that students will better understand history if they can connect it to themselves and their own experiences. That’s not necessarily false, as personal connections can make a topic more interesting to learners. But relying on these connections is likely to cultivate in them a sense of presentism, the imposition of personal values and beliefs on actors of the past, an attitude that Lyn Hunt (2002), former president of the American Historical Association, described as the greatest sin of the historian.

Further, the overemphasis on individual experience makes it difficult to provide high-quality group instruction. As Hirsch (2017) explains:

Under child-centered principles, it would seem malpractice to have all the children in a class read the very same title, and then discuss the contents. Under a communal view of education, such whole-class activity would seem the most natural thing in the world. It is by far the most lively and productive kind of classroom. (pp. 74-75)

The radical individualism that results in a me-centered curriculum like EH leads to pedagogical practices that fail to equip students with the sort of shared knowledge that fuels engaging discussions. Instead, EH encourages students to incorporate new ideas into what they already know. To some extent, this is fine, as it can help young people make sense of those ideas. But taken too far, it leads to confirmation bias, teaching young people always to interpret new information in a way that validates their current beliefs, rather than teaching them to evaluate new information on its own terms.

Prioritizing critical thinking over content

The EH model also narrows the breadth of what young students are exposed to and asked to work on collaboratively. This has largely resulted from curricular designs that place priority on technique, or so-called generic skills, over knowledge. Leading organizations, guided by certain presuppositions are placing all their eggs in the “skills” basket. For instance, the National Council for Social Studies, through its construction of the C3 Framework, makes a laudable effort to articulate general social studies skills but fails insofar as it neglects to articulate specific content knowledge. This absence leads users of the framework to make a reasonable (albeit incorrect) inference that the content doesn’t really matter; instead, it’s all about the skills. Having served on multiple social studies standards revisions committees, I saw the C3 framework pushed heavily, and this was the exact inference its advocates used.

Personal connections can make a topic more interesting to learners. But relying on these connections is likely to cultivate in them a sense of presentism, the imposition of personal values and beliefs on actors of the past.

In light of this, it seems that such a shift entails an abdication of one of public education’s most important responsibilities: equipping youth to engage in civil society (Rebell, 2018). Content knowledge is not the enemy of critical thinking; it is a necessary partner. To think critically and to offer wise insight requires sufficient knowledge as a prerequisite. Without building that tenet into social studies curricula, is it any wonder people feel so confident to pontificate on everything without taking the time that is truly necessary to build knowledge so that they can speak elegantly, persuasively, and accurately?

Within EH, the learner is literally the center of the historical universe and is asked to think critically about how all historical content, slowly expanding outward, connects with them. The hope is to build transferable skills where students will be able to always ask, “What does ‘x’ mean to me?” or “How does it relate to me?” and so forth. This, however, often results in lessons that are devoid of meaningful historical content. Guy Larkins and colleagues (1987) suggested that, in part due to the EH model, elementary-level social studies texts are repetitive, trivial, and lead to “vacuous” lessons.

The problem with this is that it relies on a fundamental misconception about skills. Over the past few decades, considerable work in cognitive psychology on the development of expertise has concluded that intellectual skills are mainly domain-specific (Ericsson et al., 2018; Tricot & Sweller, 2014). Furthermore, the level of skill is largely determined by one’s relevant knowledge. An emphasis on critical thinking rather than content prevents students from building a broad base of knowledge through which they can exhibit such skills as engaging meaningfully in civic conversation.

An expertise-oriented framework to replace EH

It is of little use to spend time critiquing a dominant paradigm without offering a possible replacement, so let us briefly consider such a proposal. In particular, since the aim of learning is to increase student knowledge and skills, we will need to base our design on the preponderance of evidence from the best currently available studies in cognitive science. Additionally, since learning is about progression toward mastery, we need to explicitly consider the elements of expertise and the pathway through which this expertise develops. Finally, we need to consider the specific domain of history and those skills and practices that one must use to engage competently in historical analysis.

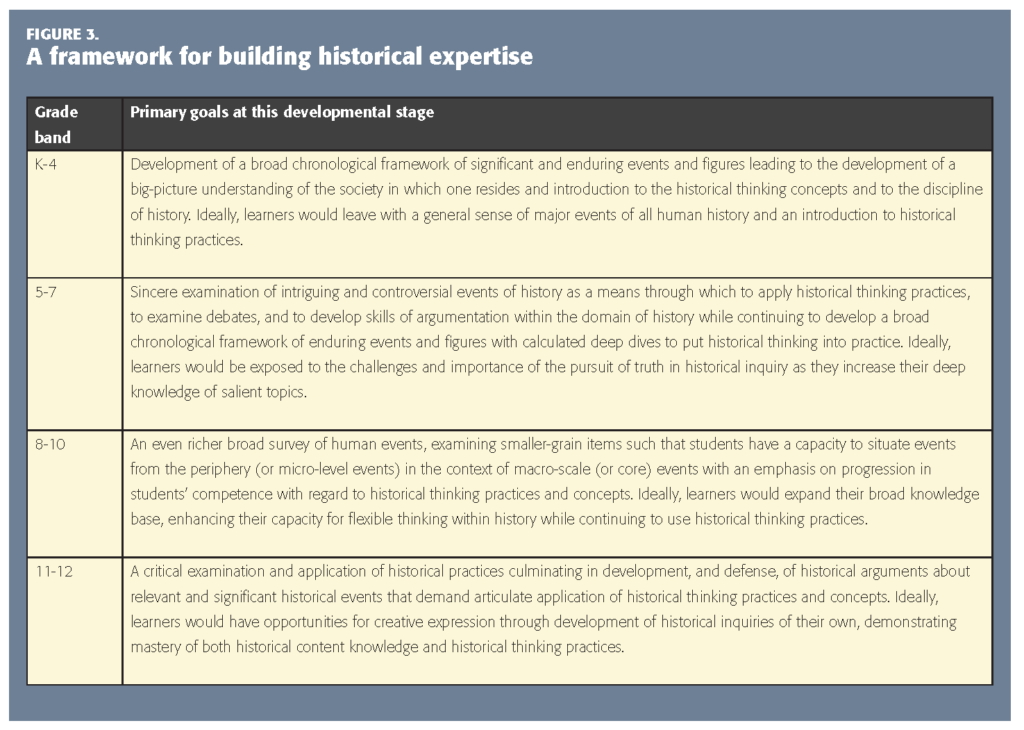

Thus, my proposed alternative framework is based on three main premises: (1) Important historical content must be taught early and built on over time, (2) Specific history practices must be articulated and integrated in a clear progression, and (3) Students must have systematic opportunities to explore content both broadly and deeply.

Specific content

The question of “what” knowledge to teach is always an uncomfortable one to ask in the social sciences because there is no clear consensus on what content matters most. However, at least a couple of basic considerations can help us answer the challenging question of “what” in a manner that is likely to improve learning outcomes. First, every society has emerged out of its own unique historical context. For example, the political system of the United States grew out of specific ideas, traditions, and movements grounded in Western civilization. If teaching about the founding of the U.S. government, say, one must acknowledge those origins and include content that illuminates those historical precursors.

Content knowledge is not the enemy of critical thinking; it is a necessary partner.

Second, each society has a collective culture and shared knowledge base that is important to its cohesion and productivity. So the question of what content to teach must be answered by way of sincere reflection on what common knowledge holds our society together. As Hirsch (1987) has argued, public schools have a responsibility to develop students’ cultural literacy, or familiarity with facts and ideas that make up the American public’s shared knowledge base, and which educated speakers and writers rely on their audiences to recognize. Of course, it can be challenging and contentious to decide what facts and ideas ought to be included. As cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham (2009) has observed, “much of what writers assume their readers know seems to be touchstones of the culture of dead white males” (p. 116), and it is always difficult to introduce new content to our cultural storehouse of knowledge. But while debates over what to include in the curriculum can be tense, we can’t avoid them — in order to function as public institutions, our public schools cannot do without a shared sense of what historical content to teach.

Specific history practices

Thankfully, over the past few decades, much work has been done to articulate what historical thinking consists of, what it looks like, and how it can be taught in the classroom. For example, in their influential volume The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts, Peter Seixas and Tom Morton (2013) identify the most essential practices that historians engage in, and they offer guideposts and examples for teachers to follow as students develop their capacities related to each. The six concepts include:

- Establishing historical significance

- Using primary source evidence

- Examining continuity and change

- Analyzing cause and consequence

- Taking historical perspective

- Attempting to understand the ethical dimension of history.

However, Seixas and Morton add, “[These] historical thinking concepts make no sense at all without the material, the topics, the substance, or what is often referred to as the ‘content’ of history” (p. 4). Knowledge, not skill, is the central factor for development of expertise (Ericsson & Pool, 2017), and Seixas and Morton’s explicit acknowledgment of the role of content makes their model especially appropriate in an expertise-oriented framework.

Breadth and depth

Real critical thinking and creativity in history requires both broad and deep knowledge, which complement each other. Studying historical topics broadly equips learners with a big-picture view that allows them to contextualize the details they go on to learn. That is, knowing things broadly makes it possible for students to examine particularly significant eras or events in depth, using key historical thinking practices. Then again, if students focus on exploring just a few topics deeply, their knowledge can become too narrow — it’s important always to alternate between depth and breadth of study.

In sum, I argue for an approach to history instruction that is informed by recent research in cognition, with an emphasis on teaching historical thinking concepts within a content-rich curriculum. (For a visual representation of my proposed framework, see Figure 3.) To pursue such an approach is to take advantage of what Dylan Wiliam (2018) identifies as low-hanging fruit in public education — it should be a relatively straightforward task to infuse the teaching of history with specific content, a number of

subject-specific practices, and some opportunities for students to alternate between breadth and depth of study. If we do so, we can make an immediate and significant impact on student learning.

References

Akenson, J.E. (1987). Historical factors in the development of elementary social studies: Focus on the expanding environments. Theory and Research in Social Education, 15 (3), 155-171.

Becker, J.M. (1965). Emerging trends in the social studies. Educational Leadership, 22 (5), 317-321, 359.

Brophy, J. & Alleman, J. (2006). A reconceptualized rationale for elementary social studies. Theory and Research in Social Education, 34 (4), 428-454.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Egan, K. (2005). Students’ development in theory and practice: The doubtful role of research. Harvard Educational Review, 75 (1), 25-41.

Ericsson, K.A., Hoffman, R.R., Kozbelt, A., & Williams, A.M. (2018). The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ericsson, K.A. & Pool, R. (2017). Peak: Secrets from the new science of expertise. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Fernandez-Armesto, F. (1997). Truth: A history and a guide for the perplexed. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books.

Fischer, F. (2011). The historian as translator: Historical thinking, the Rosetta Stone of history education. Historically Speaking, 12 (3), 15-17.

Hirsch, E.D. (1987). Cultural literacy: What every American needs to know. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Hirsch, E.D. (2017). Why knowledge matters: Rescuing our children from failed educational theories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hunt, L. (2002, May 1). Against presentism. Perspectives on History.

Larkins, A.G., Hawkins, M., & Gilmore, A. (1987). Trivial and noninformative content of elementary social studies: A review of primary texts in four series. Theory and Research in Social education, 15 (4), 299-311.

LeRiche, L.W. (1987). The expanding environments sequence in elementary social studies: The origins. Theory and Research in Social Education, 15 (3), 137-154.

Rebell, M.A. (2018). Preparation for capable citizenship: The schools’ primary responsibility. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (3), 18-23.

Seixas, P. & Morton, T. (2013). The big six historical thinking concepts. Toronto, CA: Nelson.

South Carolina Department of Education. (2018). South Carolina College- and Career-Ready Standards (Draft). Columbia, SC: Author.

Tricot, A. & Sweller, J. (2014). Domain-specific knowledge and why teaching generic skills does not work. Educational Psychology Review, 26, 265-283.

Wade, R. (2002). Beyond expanding horizons: New curriculum development directions for elementary social studies. The Elementary School Journal, 103 (2), 115-130.

Wiliam, D. (2018). Creating the schools our children need: Why what we’re doing now won’t help much (and what we can do instead). West Palm Beach, FL: Learning Sciences International.

Willingham, D. (2009). Why don’t students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Citation: Krahenbuhl, K.S. (2019). The problem with the expanding horizons model for history curricula. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (6), 20-26.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kevin S. Krahenbuhl

KEVIN S. KRAHENBUHL is an assistant professor of education at Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro. He is the author of The Decay of Truth in Education .