Momentum is growing to improve learning and care during the early years, creating significant opportunities for schools and districts to address gaps.

Momentum is growing to improve learning and care during the early years, creating significant opportunities for schools and districts to address gaps.

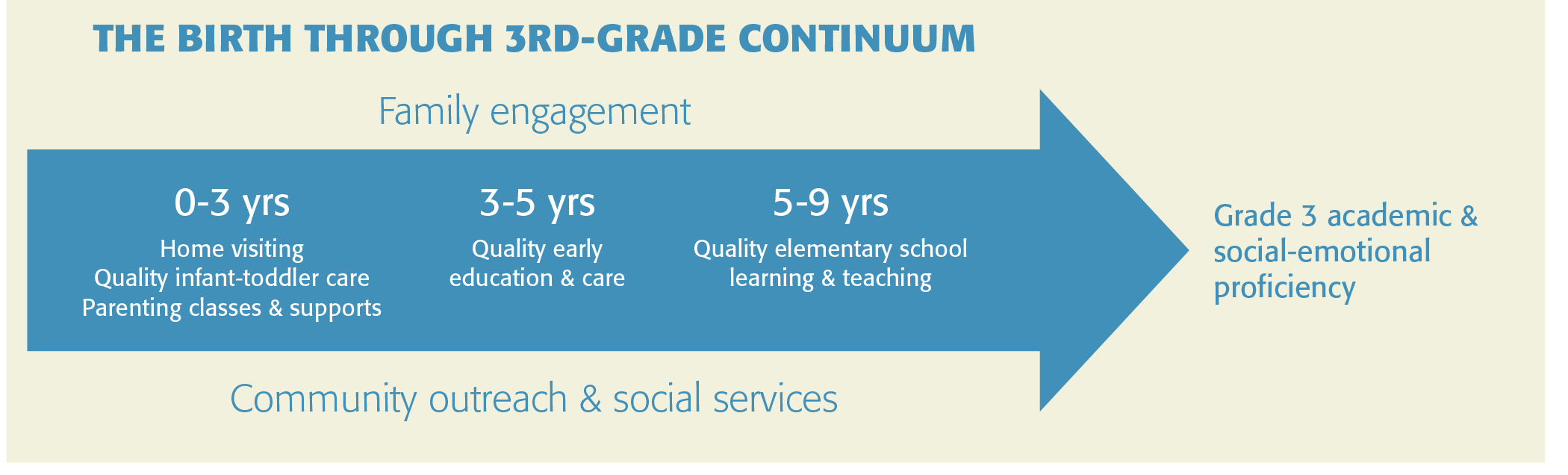

School districts on the leading edge of the Birth through 3rd-Grade movement have demonstrated unprecedented success raising the achievement of low-income students by developing coherent strategies focused on the early years of learning and development. These communities aren’t merely improving preschool. Rather, they’re building high-quality early education systems that align services from birth through age 9.

Two U.S. school districts on the leading edge of the Birth-3rd movement have shown striking results based on this approach.

- Sprawling Montgomery County, Md., just outside Washington, D.C., has improved results for all students while significantly reducing gaps between affluent and low-income students. The district has achieved remarkable rates of kindergarten readiness (90%), 3rd-grade reading proficiency (88%), and high school graduation (90%).

- Union City, N.J., is a heavily low-income and Latino urban district that outperforms the New Jersey state averages in reading and math in one of the highest performing states in the country and graduates 90% of its students.

Common to both districts are aligned systems of education and care that begin early and continue through the elementary school years, providing strong foundations for continued academic success (Childress, Denis, & Thomas, 2009; Kirp, 2013; Marietta, 2010; Marietta & Marietta, 2013a).

School and district leaders must make improving early education a strategic priority.

Birth-3rd

Inspired by a mounting and compelling body of research and examples of pioneering communities, the Birth-3rd movement includes the 120-community Campaign for Grade-Level Reading, a range of philanthropic efforts, and vigorous activity by state governments. At the federal level, the Race to the Top-Early Learning Challenge funding program and President Obama’s proposal to expand preschool for all four-year-olds indicate growing recognition of the importance of the foundational first nine or so years of education and care.

Given the current demands on principals and district leaders, there is perhaps a natural temptation to respond to the idea of improving education and care in the early years with a detached hopefulness that students will soon arrive at kindergarten with higher levels of readiness. Yet Montgomery County and Union City did much more than improve preschool. They built systems that included K-3 as well. Building such systems requires that school and district leaders embrace improving early education as a strategic priority and provide leadership in implementing three overarching strategies in their communities.

Why a Birth-3rd strategy?

Gaps between low-income and middle-class children appear early and increase over time. Such gaps in social-emotional and academic readiness for kindergarten lead to gaps in literacy and math proficiency by 3rd grade, which in turn lead to gaps in high school graduation rates and college- and career-readiness (Heckman, 2012; Torgesen, 2004; Hernandez, 2011).

High-quality early childhood services can effectively address these gaps. A preponderance of evidence demonstrates that quality home-visiting, preschool, and early literacy programs yield large gains in children’s learning and development (Heckman, 2012; Yoshikawa et al., 2013; Pressley, 2005).

Multiple supports are required. Addressing large gaps requires improving the quality of services for children at each level of development and integrating and aligning these services in order to have the most effect. (See continuum graphic above.)

Leading edge communities demonstrate the power of comprehensive approaches. The Child-Parent Centers in Chicago, the Harlem Children’s Zone, Montgomery County, Union City, and the Strive Program in Cincinnati have demonstrated impressive results, fueling increased financial support for birth-3rd services, policy change, and innovative projects at the federal, state, and community levels (Kirp, 2013; Jacobson, Jacobson, & Blank, 2012; Tough, 2012; Sullivan-Dudzic, Gearns, & Leavell, 2010; Marietta & Marietta, 2013b).

Role of schools and districts

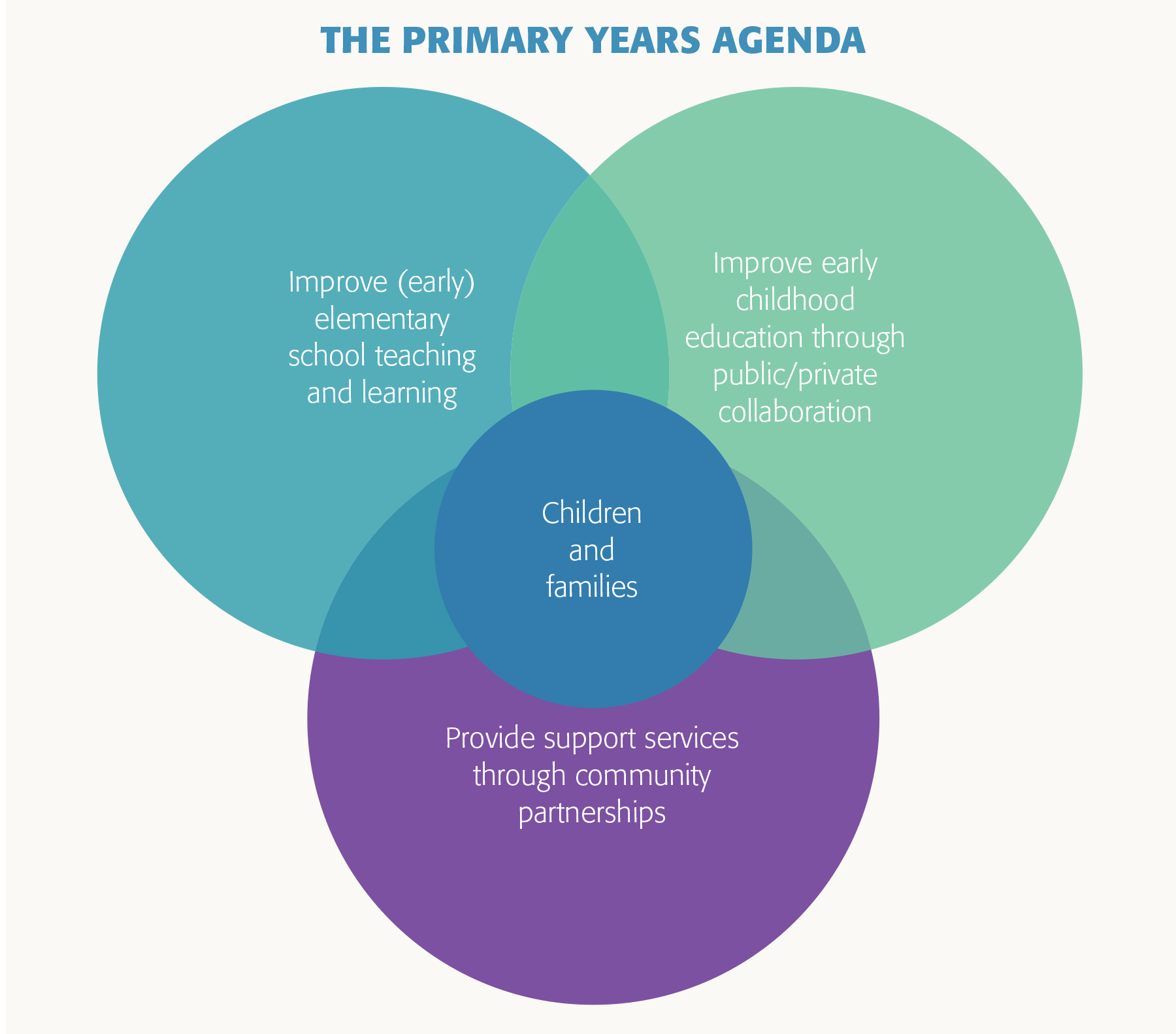

Drawing on the experience of Birth-3rd initiatives in Massachusetts and leading edge sites around the country, I suggest that schools and districts implement three strategies to form a comprehensive, integrated approach to improving early learning outcomes for children. These strategies entail significant coordination responsibilities. Given the demands on building principals and school leadership teams, districts — ideally with state support — must take the lead in spearheading each of these strategies, with principals providing critical support by contributing ideas, supporting implementation in their buildings, and developing the capacity and expertise to lead improvement in early years teaching and learning.

#1. Improve (early) elementary school teaching and learning.

The early elementary grades often suffer from relative neglect. These are untested grades. School and district leaders may have less knowledge about early childhood education, and, in many districts, early childhood does not have as much internal political power as other departments. Often low-performing teachers are moved from tested grades to kindergarten, 2nd-grade, and even 1st-grade classes. Inadequate funding for full-day kindergarten, despite its clear benefits, is a further instance of neglect (Children’s Defense Fund, 2012).

Massachusetts provides an example of how one state began addressing the need for early grades improvement. A few years ago, the state began by creating a small grant project to support the alignment of curriculum, instruction, and assessment in preK-3 in over 40 districts. Districts were required to create vertical preK-3 teams that would conduct needs assessments of the early learning pathways in their districts and develop strategies to address high-priority needs.

While Massachusetts is a high-performing state and has long had rigorous 3rd-grade tests, these teams nonetheless identified a range of important needs: gaps in expectations between preK and kindergarten and between kindergarten and 1st grade, misaligned curricula and assessments, lack of consistent instructional approaches across the early grades, and inadequate attention to oral language development, vocabulary instruction, and development of social-emotional skills. Family engagement and improving the transition from preschool were also identified as critical areas of improvement (Jacobson, 2011).

To address such needs, schools, districts, and states need to improve curricula, formative assessments, and student progress monitoring mechanisms, taking into account how young children best learn and the full range of developmental domains: cognitive development and general knowledge, social and emotional development, language and communication development, approaches toward play and learning, and physical development and well-being (NAEYC, 2002). Importantly, they then need to enact these improvements by supporting teachers through professional development, coaching, and professional learning communities, using them to improve developmentally appropriate teaching and learning in classrooms (Jacobson, 2010). Creating and enacting such teaching and learning “guidance systems” is a critical component of school improvement, as is a robust family engagement strategy, including supporting families in supporting their children’s learning and development (Bryk, 2010).

The small grants that Massachusetts awarded to districts set off a flurry of activity. In many cases, educators had never had the chance to work together across grades and welcomed the opportunity. The participation of general education and special education educators enhanced the opportunity further, as did the state’s validation of the importance of the work. Once they identified their core issues, many teams undertook ambitious projects, especially given the small size of the grants — mapping curricular expectations, developing common formative assessments and rubrics, implementing response-to-intervention systems, developing cross-grade instructional approaches (e.g., Six Trait Writing), creating home-visiting programs, and strengthening the oral language, vocabulary components, and social-emotional components of the early grades curricula.

These preK-3 projects also led to important strategic and organizational shifts, including greater recognition of early learning as a priority among senior district leadership and greater collaboration across district departmental silos (Jacobson, 2011).

As districts develop and improve their early elementary guidance systems through the kinds of projects suggested by the Massachusetts vertical teams, they build their capacity to fulfill their early learning leadership role in their communities more effectively.

Improving teaching and learning in public school early grade classrooms and collaborating with community-based providers to improve preschool quality are two critical elements in Birth-3rd efforts.

#2. Improve early childhood education through public/private collaboration.

In the U.S., preschool education and care are provided by a mixed delivery system of family day care, community-based preschool centers, Head Start, and school districts, all supported by a complex maze of funding streams. Much work is underway by states improving quality, including through Quality Rating Improvement Systems screening and assessment systems, and improved training and certification (Christie & Rose, 2012). This state-level work is crucial, but building capacity and improving quality throughout a community also requires aligned systems and effective professional development at the community level. School districts can help build such structures by partnering with community-based providers to form early education collaboratives with the goal of improving preK-3rd education across community-based and public settings (Wat & Gayl, 2009).

While school and district leaders have enough on their plates without actively engaging with their preschool communities, it is this collaboration that has been key to improving readiness for kindergarten and 1st grade in Montgomery County, Union City, and other communities. (Marietta, 2010; Mead, 2009; Kirp, 2013; Sullivan-Dudzic, Gearns, & Leavell, 2010). For early childhood collaboratives to be effective, districts must make early education a strategic priority and provide significant district support from superintendents, directors of curriculum and instruction, literacy coaches, and early childhood coordinators. States, in turn, can facilitate such district support by providing targeted funding, technical assistance, and opportunities for communities to exchange best practices (Christie & Rose, 2012; Wat, 2012; Jacobson, 2011).

School and district leaders must establish a climate of mutual respect when working with preschool providers and emphasize the two-way nature of the learning collaboration. Differences in compensation, resources, and status notwithstanding, community-based preschools value relationships with public schools and have early childhood expertise to bring to the table. Partnerships often begin by working on alignment and transition with reference to new Common Core State Standards and state ratings improvement systems. First steps may include discussing preschool and kindergarten learning standards, designing transition forms, and making cross-site classroom visits. Public prekindergarten and kindergarten teachers can serve in boundary-spanning roles, connecting with their community-based early childhood counterparts as well as their public school colleagues in grades 1-3. Done with care, these valuable initial activities build mutual respect and a sense of joint efficacy that can provide a foundation for more ambitious plans and projects, including joint professional development for teachers and leaders.

Union City developed a communitywide preschool curriculum and a cadre of master prekindergarten teachers who provided extensive support both to district and community-based teachers. These master preK teachers then helped redesign kindergarten as well (Kirp, 2013). In Springfield, Mass., district and community-based educators are working jointly on an alignment team to select a common preschool curriculum and formative assessments for the community and to provide common professional development experiences for preK and kindergarten teachers. Boston began by developing a highly effective preK curriculum and coaching model that has secured some of the best preschool outcomes in a large program in the country (Weiland & Yoshikawa, 2013). Based on this success, the district is supporting community-based preschools in implementing the model. Further, the early childhood department has now developed a kindergarten curriculum and professional development model and is working with the district to expand its work to include grades 1-3.

Improving teaching and learning in public school early grade classrooms and collaborating with community-based providers to improve preschool quality are two critical elements in Birth-3rd efforts. Yet addressing the needs of students who grow up in poverty and other stressful circumstances requires more than high-quality learning experiences; it requires the integrated provision of health and social services to support families and children at each developmental stage: birth to age 3, preK, and K-3 (and beyond).

#3. Provide support services through community partnerships before birth and through 3rd grade — and beyond.

Two clear and related strategies for providing comprehensive services for children in an aligned fashion have emerged:

- Developing communitywide early childhood partnerships with the wherewithal to implement a comprehensive vision and strategic plan; and

- Coordinating the provision of integrated services at the school or early childhood center site.

Cross-sector partnerships — In Montgomery County, a nonprofit Collaboration Council for Children, Youth, and Families developed a comprehensive early childhood plan and a Children’s Agenda of seven actionable goals for the county. This plan led to an aligned system that includes center-based comprehensive services for the neediest children and their families from birth to age 5, aligned Head Start and preschool classrooms, and targeted summer and afterschool programming for early elementary school students (Marietta, 2010).

Likewise, as mentioned, over 120 communities across the country have created early learning partnerships with the specific goal of improving reading by 3rd grade in association with the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Campaign for Grade-Level Reading. For example, in Pittsfield, Mass., a 60-member group of civic leaders has committed to the Pittsfield Promise — a goal of 90% reading proficiency by 2020. The community has developed five broad objectives in pursuit of this goal, and the local United Way is providing critical functions by coordinating groups working on home visits, community awareness, family engagement, and improving preschool education.

Full-service schools and early childhood centers — Communitywide partnerships create structures for effectively engaging the full range of community institutions in early childhood efforts, including preschool director associations, hospitals, pediatrician and nursing groups, libraries, and museums. An effective way of reaching students directly and in an integrated fashion is by coordinating services at the school or center site. One example of such integration is through the fast-growing model of the community school.

Community schools supplement their traditional academic offerings with a suite of services in partnership with community organizations. Principals collaborate with partners through a cross-sector leadership team and a resource coordinator who coordinates a range of services, including health, mental health, after-school, early childhood, summer programming, and mentoring and tutoring (Melaville, Jacobson, & Blank, 2011). Community schools have expanded greatly in recent years, scaling to encompass large numbers of schools in Chicago, Tulsa, and Cincinnati. Since adopting this strategy, Cincinnati has become the highest-performing urban district in Ohio, narrowing achievement gaps and improving graduation rates (Jacobson, Jacobson, & Blank, 2012).

Momentum around three strategies

Momentum is growing at the federal, state, and community levels to improve learning and care during the primary years. Sustaining this momentum in the current fiscal climate and in an environment wary of increased government spending will require that educators make the case for investment by demonstrating the effect of their programs. In turn, achieving such demonstrations will require innovative program design, rigorous implementation, and mid-course correction using performance benchmarks and rigorous evaluation (Lesaux, 2010; Kauerz & Coffman, 2013). These challenges notwithstanding, the Birth-3rd movement creates a highly promising opportunity for school, districts, and communities to reduce gaps while raising achievement and life chances for all children through three strategies: improving preK-3rd education in elementary schools; raising the quality of preschool education and care throughout a community through early education collaboratives; and providing comprehensive health and social services to young children through community partnerships.

References

Bryk, A.S. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 91 (7), 23-30.

Children’s Defense Fund. (2012). The facts about full-day kindergarten. Washington, DC: Children’s Defense Fund.

Childress, S.M., Denis, P.D., & Thomas, D.A. (2009). Leading for equity: The pursuit of excellence in the Montgomery County Public Schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Christie, K. & Rose, S. (2012). A problem still in search of a solution: A state policy roadmap for improving early reading proficiency. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States.

Heckman, J. (2012, Sept. 1). Promoting social mobility. The Boston Review. www.bostonreview.net/forum/promoting-social-mobility-james-heckman

Hernandez, D.J. (2011). Double jeopardy: How 3rd-grade reading skills and poverty influence high school graduation. Baltimore, MD: The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Jacobson, D. (2010). Coherent instructional improvement and PLCs: Is it possible to do both? Phi Delta Kappan, 91 (6), 38-45.

Jacobson, D. (2011). Improving the early years of education in Massachusetts: The p-3 curriculum, instruction, and assessment project. Malden, MA: Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. www.doe.mass.edu/kindergarten/PK-3report.pdf

Jacobson, R., Jacobson, L., & Blank, M. (2012). Building blocks: An examination of the collaborative approach community schools are using to bolster early childhood development. Washington, DC: Coalition for Community Schools, Institute for Educational Leadership.

Kauerz, K. & Coffman, J. (2013). Framework for planning, implementing, and evaluating preK-3rd grade approaches. Seattle, WA: University of Washington College of Education.

Kirp, D.L. (2013). Improbable scholars: The rebirth of a great American school system and a strategy for America’s schools. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lesaux, N. (2010). Turning the page: Refocusing Massachusetts for reading success. Boston, MA: Strategies for Children.

Marietta, G. (2010). Lessons in early learning: Building an integrated preK-12 system in Montgomery County Public Schools. New York, NY; Washington, DC: Foundation for Child Development, The Pew Center for the States.

Marietta, G. & Marietta, S. (2013a). PreK-3rd’s lasting architecture: successfully serving linguistically and culturally diverse students in Union City, N.J. New York, NY: Foundation for Child Development.

Marietta, G. & Marietta, S. (2013b). The promise of preK-3rd: Promoting academic excellence for dual language learners in Red Bank Public Schools. New York, NY: Foundation for Child Development.

Mead, S. (2009). Education reform starts early: Lessons from New Jersey’s P-3 efforts. Washington, DC: New America Foundation.

Melaville, A., Jacobson, R., & Blank, M.J. (2011). Scaling up school and community partnerships: The community schools strategy. Washington, DC: Coalition for Community Schools, Institute for Educational Leadership.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). (2002). Early learning standards: Creating the conditions for success. Washington, DC: Author.

Pressley, M. (2005). Reading instruction that works: The case for balanced teaching. New York: NY: Guilford Press.

Sullivan-Dudzic, L., Gearns, D., & Leavell, K. (2010). Making a difference: 10 essential steps to building a preK-3 system. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Torgesen, J.K. (2004, Fall). Avoiding the devastating downward spiral: The evidence that early intervention prevents reading failure. American Educator. www.aft.org/newspubs/periodicals/ae/fall2004/torgesen.cfm

Tough, P. (2012). How children succeed: Grit, curiosity, and the hidden power of character. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Wat, A. & Gayl, C. (2009). Beyond the school yard: Pre-K collaborations with community-based providers. Washington, DC: The Pew Center on the States.

Wat, A. (2012). Governors’ role in aligning early education and K-12 reforms: Challenges, opportunities, benefits for children. Washington, DC: National Governors Association.

Weiland, C. & Yoshikawa, H. (2013). Impacts of a prekindergarten program on children’s mathematics, language, literacy, executive function, and emotional skills. Child Development, 84, 2112-2130.

Yoshikawa, H., Weiland, C., Brooks-Gunn, J., Burchinal, M., Espinosa, W., Gormley, W., … Zaslow, M. (2013). Investing in our future: The evidence base on preschool education. New York, NY: Society for Research in Child Development, The Foundation for Child Development.

CITATION: Jacobson, D. (2014). The primary years agenda: Strategies to guide district action. Phi Delta Kappan, 96 (3), 63-69.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David Jacobson

DAVID JACOBSON is a principal researcher and technical assistance adviser, Education Development Center, Waltham, Mass. He writes the P-3 Learning Hub blog .