One school’s strategies to offer effective emotional support for students who face serious stressors can easily be replicated in any school, whether students are dealing with major trauma or the kinds of everyday challenges that all kids face.

Jeremy entered the school, visibly angry and despondent. When his homeroom teacher gently asked him how he was doing, there was no response. He sat at his desk with a scowl on his face, refusing to follow any directions or communicate. Jeremy clearly needed some time outside the classroom. With some prodding, the school counselor took him to an area where they could talk without other students around. After about five minutes of silence, Jeremy finally spoke: “I’m tired. I didn’t sleep last night. My mother got drunk again. My sister and I had to get her to bed and watch over her. I really hate staying at that place.” That place is the shelter where Jeremy and his family live now that they are homeless.

Fortunately, most middle school students do not experience the kind and intensity of stress that Jeremy describes. But many of them do, and for them it can be a struggle just to get through the school day, much less focus on academics. The question is, what can schools realistically be expected to do to meet such needs?

This article reviews the many strategies that one school has come up with, over the past 20 years, to provide effective emotional support for students who, like Jeremy, face serious stressors in their daily lives. Further, all of these strategies can easily be replicated, and while they were created for a particular set of at-risk students, they can be used in any school, whether students are dealing with major trauma or the kinds of everyday challenges that all kids face.

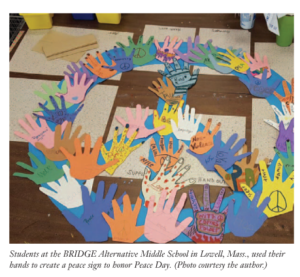

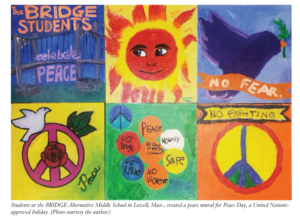

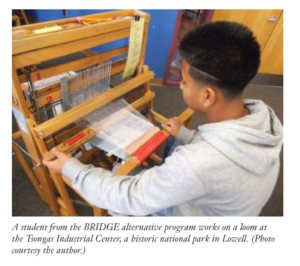

At the BRIDGE Alternative Middle School in Lowell, Mass., all students are highly stressed. We specialize in serving students ages 12-16 who have exhibited behavioral problems in traditional school settings, including problems such as truancy, multiple suspensions, mental health issues, peer conflicts, family dysfunction, academic problems, and gang involvement. Students referred to BRIDGE are often involved with the court system and/or with the state’s Department of Children and Families, and many have been in and out of specialized hospital placements and residential or respite care facilities. When they arrive at BRIDGE, they tend not only to be struggling in school but also exhibiting problems at home or in the community. In short, the students who come to us have experienced significant stress for children their age, and they bring a heightened level of emotional sensitivity with them to school.

Growing up in a chaotic and unstable environment creates chronic early stress (often referred to as toxic stress), which can affect children’s ability to regulate their emotions or respond appropriately to disappointments and provocations. As the journalist Paul Tough notes, for such kids, “[S]mall setbacks feel like crushing defeats; tiny slights turn into serious confrontations” (2016, p. 15). Further, because stress hormones disrupt the parts of the brain that affect learning, memory, mood, relational awareness, and executive function (Souers & Hall, 2016, p. 22), students with these histories tend to develop attendance problems, suffer academically, get into fights with other students, swear at their teachers, and walk out in the middle of the school day. It’s no surprise, then, that many students at the BRIDGE struggled greatly in the more traditional schools they attended previously.

After enrolling at the BRIDGE, however, these same students reduce their suspension rates, increase their attendance, and improve their academic growth. We’ve been able to get such results, consistently, largely because we’ve developed a range of effective ways to help prevent and respond to problems that arise from stress, frustration, rage, and emotional dysregulation. Whether in an alternative setting or a more typical classroom, a number of small steps can lead to a significantly improved emotional climate and a more stable, healthy school culture.

#1. Create a calm environment.

Drop Everything and Relax (DEAR)

Stress reduction can be taught, learned, and practiced successfully in the classroom. After receiving trauma sensitivity training from the Trauma Justice Institute and stress management training at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, several BRIDGE staff became highly skilled at leading students and staff in a routine stress reduction activity involving guided imagery. (In our experience, local funders have been more than willing to help cover the costs of such training.) Every morning, they guide the entire school through 10 minutes of DEAR time, which focuses on relaxing the mind and body. In addition, staff lead lessons on and discussions about stress throughout the year, and students develop a strong understanding of when, how, and why it occurs, as well as what tools can be used to prevent and reduce it.

Positivity

We’ve found that when we provide explicit recognition of positive behaviors, students become more likely to repeat such behaviors in the future. In fact, making regular efforts to call attention to good behavior has had a great effect on the school climate overall. At the BRIDGE, we’ve given this practice a name, Positivity, and we hand out what we call positivity points, which formally acknowledge those moments when, for example, students show gratitude, kindness, and support for each other.

Stress balls

A stress ball (or fidget) is nothing more than a small, flexible object that students can hold during the school day and which they can squeeze or play with absentmindedly while in class. Considering how inexpensive they are (or free, if students make them as a class project), they provide a pretty effective outlet for anger and stress, giving students a simple way to release tension and stay calm and focused on their work. And while some educators may worry that students will throw them around or use them to distract each other, we’ve found the opposite: Students tend to pull them out discreetly when they feel a need to release some nervous energy, and this helps to prevent them from tapping, making noise, or otherwise disrupting other students.

The BRIDGE has a licensed therapy dog on site, and she makes a great contribution to the school’s emotional climate, often helping staff connect with students who are frustrated, depressed, and/or angry, especially if they seem unwilling to talk. In fact, whenever students are sent out of class for misbehavior, they are given the option to visit with the dog before they fill out an incident report. In recent years, many colleges have also come to recognize the value of therapy animals, especially to ease the stress associated with midterms and final exams. (If interested, you might start by contacting local therapy dog licensing agencies to see if they will schedule a visit.)

Classical music

We’ve found that students are calmer when they have regular opportunities during the school day to listen to soothing music — we tend to play classical music, both in the hallways and during individual work time. Also, music players with headphones are available to students on an individual basis.

Soothing visuals

We’ve created counseling offices and other spaces that feature pastel colors and soft light, designed to offer calm settings where students can go when they need to ease stress or de-escalate a conflict, and we’ve collected a number of photographs of soothing landscapes (such as beaches, mountainsides, and waterfalls) that students can use as visualization tools when trying to rein in their emotions. Not every student finds these strategies helpful, but some of them do seem to respond to one or another kind of visual environment, so we make a range of them available.

#2. Ensure that students feel physically and emotionally safe.

Human Dignity Policy

This policy is the cornerstone of the BRIDGE program, defining an explicit set of school values, behavioral norms, and beliefs about how students and staff should communicate with and treat each other. By keeping expectations high and setting clear, consistent limits, the Human Dignity Policy ensures that students know that they cannot say rude, mean, or disrespectful things to one another — and it explains why it would be unacceptable to do so. Staff actively monitor violations against human dignity and redirect behavior with the goal of averting conflicts and explosive behaviors before they happen. In our experience, such a policy — along with constant efforts to reinforce it — provides an invaluable means of reducing stress. Not only does it give students a common language in which to discuss such topics, but it provides them great relief to know that the school will not tolerate negative social interactions and that they don’t have to be constantly on guard against bullying, intimidation, and other negative behaviors.

Verbal and physical de-escalation skills

With help from the Crisis Prevention Institute, we train staff in effective ways to handle students in crisis, which allows everyone to feel safe by letting them see that the school can be counted on to control negative outbursts right away. When situations begin to escalate, our staff know to stay calm, and they understand that they are expected to intervene. No school is an entirely safe environment, but we recognize that students look to us to de-escalate crises immediately and as effectively as we can. If they trust us to do so, then they can let go of a major source of stress.

Take Five space

To help students become more independent and more able to regulate and redirect their own emotions, they must have chances to refocus themselves before a situation spins out of control. At the BRIDGE, we have created visibly private areas within each classroom, and at any time, if students feel frustrated or need a breather, they can ask to go to one of those spaces and sit there for five minutes. Of course, there doesn’t have to be a designated area for this purpose — in a more traditional setting, for example, teachers can encourage students to go to the water fountain or run a classroom errand as a means of taking a break and calming themselves.

Drawing or journaling

We’ve found that when students appear sad, depressed, or even despondent, it can be useful to encourage them to draw or write in a journal. For some, coloring with markers or colored pencils for five minutes may be enough to pull them out of dark thoughts, allow them to begin working through weighted emotions, and make it possible for staff to engage them in conversation. For some students, it may even be helpful to make this part of their regular schedule, giving them five minutes of coloring or journaling time every day.

Independent working spaces

At times, staff members will identify students (or students will identify themselves) as being unable to function calmly or safely within the classroom. Schools can create another space for such situations, which enables students to stay in school, working independently, until such time as they are able to rejoin the group. This also helps other students, too, since it prevents a crisis that might have erupted in the classroom.

#3. Give students a way to communicate their feelings.

Check-ins

For some students, scheduling a daily or weekly check-in time provides a critical outlet to talk about issues that they might not otherwise be able to share with anyone. Check-ins can be an important opportunity for staff members to gain their trust, showing that they care about what goes on in their individual lives, not only in school but also at home, with friends, and in the community. Sometimes check-ins are the teacher’s idea; other times, students will refer themselves. Either way, the check-in is a powerful resource for many BRIDGE students, motivating some to get themselves to school in the morning and giving others the support they need to get through the day.

Signal charts

This is a quick and simple way to check on how students are feeling. As they arrive at school or enter the classroom, each student chooses a slip of paper with a drawing of a happy, cool, sad, or angry/frustrated face, and they attach it to a chart by their name. If they want to be more specific, they can write in how they are feeling, or they can note that they want to speak to a staff member. At the BRIDGE, we use a signal chart every morning as students enter the building. The chart gives staff a heads-up about issues students may be dealing with and reminds students every day that the school team cares about them.

Mood cards

Opening each class period with mood cards is another way we try to get ahead of problems before they erupt. As students take their seats, they display one of three colored index cards: green for “I’m cool,” yellow for “I’m unsure,” or red for “I’m frustrated.” This lets the teacher know whether they might want to keep an eye on a couple of students, make a point of checking in with them, or consider requesting support from a school counselor.

Mood checks

At the beginning of a class period, BRIDGE teachers also might pass a ball around the room, asking each student to rate his or her mood on a scale of 1-5. (Only the person holding the ball is permitted to speak, so others must listen without interrupting.) While this activity requires a little more time than the tools above, it helps build relationships between students and teachers and reinforces the school’s larger effort to encourage students to pay attention to each other’s feelings and treat each other with respect, sympathy, and compassion.

At the BRIDGE, each day ends with a student-led discussion called a Wrap-Up, giving students and staff a chance to reflect on the day and raise pressing questions and concerns. Everybody sits in a circle, and they have to come up with and agree on rules for participating (for example, one person speaks at a time, and that person gets to choose the next speaker). In short, the idea is to create a safe, positive space for students to talk with each other about important topics of their choosing, build a sense of community, and practice expressing themselves and responding to each other respectfully.

Restorative justice

Finally, like a growing number of schools across the country, the BRIDGE practices a form of restorative justice, which is a judicial process that gives students who’ve harmed others a way to make things right. Following a negative incident, everybody involved — including victims, witnesses, and offenders — has the chance to speak, with the goal of understanding what happened and why, and to agree on a way to repair any physical and/or emotional damage. Typically, we use this process to respond to peer conflicts, which tend to have a negative effect on the entire classroom or school community and not just on the individual students who were involved.

Conclusion

Though it is not easy to support and educate young people who have experienced toxic stress, trauma, and adverse situations, the BRIDGE program has succeeded in cultivating a warm, positive, and nurturing environment for students. Over the past 19 years, we’ve maintained an average attendance rate of 89%. Between the time they enter the program and the time they exit, students see, on average, a 76% increase in scores on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills. By the time they leave us, at the end of the 8th grade, 64% of BRIDGE students have significantly reduced their suspension rates from when they attended a traditional middle school.

Take it from those of us who work with a population of severely stressed, at-risk students: Recognizing what children go through is not enough; educators must be determined to create and implement the many kinds of strategies that meet their needs. The nation’s public schools can help all students succeed, whether those students are dealing with minor stressors or major traumas, but doing so will require a great and lasting commitment.

References

Souers, K. & Hall, P. (2016). Fostering resilient learners: Strategies for creating a trauma-sensitive classroom. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Tough, P. (2016). Helping children succeed: What works and why. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Originally published in March 2017 Phi Delta Kappan 98 (6), 42-46. © 2017 Phi Delta Kappa International. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ellen J. Spiegel

ELLEN J. SPIEGEL is founding director of the BRIDGE Alternative Middle School, Lowell, Mass.