During Justice Stevens’ 35-year tenure on the Supreme Court, he spoke out on a variety of issues related to schools and student rights.

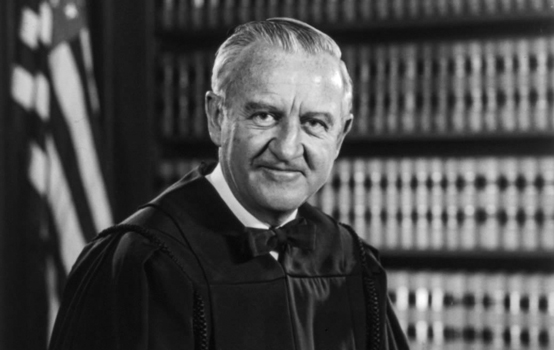

On July 6, 2019, retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens passed away. He served our nation for many years and in many capacities. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy the day before D-Day and served as a code breaker. After law school, he clerked for Justice Wiley Rutledge. He held several positions as special counsel to the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Attorney General’s office, was appointed to the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals for five years, and served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 35 (1975-2010).

Although he was appointed by a Republican president (Gerald Ford), Stevens was the anchor of the more liberal wing of the Supreme Court for many years. He spoke out for separation of church and state, desegregation, civil liberties, and student rights. He served long enough to be part of the Court when it was liberal, conservative, and split. During his early service, he was junior to noted liberal justices, but for much of his later tenure, he was a liberal within a conservative majority. As such, he may be remembered for both dissents and majority opinions in numerous areas related to education.

Separation of church and state

Wallace v. Jaffree (1985)

Stevens wrote the majority opinion (6-3) when the Court struck down an Alabama law authorizing a moment of silence in the public schools for meditation or voluntary prayer. He wrote that the practice was “not consistent with the established principle that the government must pursue a course of complete neutrality toward religion.”

Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000)

The Court struck down (6-3) a Texas school district’s policy permitting student-led prayers before football games as a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause. Stevens wrote the majority opinion, stating that “These invocations are authorized by a government policy and take place on government property at government-sponsored school-related events. . . . An objective Santa Fe High School student will unquestionably perceive the inevitable pregame prayer as stamped with her school’s seal of approval.”

Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002)

Stevens dissented in this (5-4) case, which upheld the public funding of tuition vouchers for use at private schools, including religious schools. Arguing that such funding of religious schools violates the Establishment Clause, he wrote:

[T]he voluntary character of the private choice to prefer a parochial education over an education in the public school system seems to me quite irrelevant to the question whether the government’s choice to pay for religious indoctrination is constitutionally permissible . . . . Whenever we remove a brick from the wall that was designed to separate religion and government, we increase the risk of religious strife and weaken the foundation of our democracy.

Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow

A public school district policy required the daily voluntary recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in classrooms, but a parent argued that the 1954 inclusion of the words “under God” made the daily recitation a violation of the Establishment Clause. The Court unanimously found, with Stevens writing the opinion, that the parent did not have standing to raise the issue. As such, they were able to sidestep the controversial Establishment Clause issue. However, three Justices wrote three separate concurrences in which they stated they believed there was no Establishment Clause violation.

Desegregation

Wygant v. Jackson (1986)

The Court (5-4) invalidated a school district layoff policy that gave preferential protection to underrepresented groups, holding that it was unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause. Stevens dissented:

I believe that we should first ask whether the Board’s action advances the public interest in educating children for the future. If so, I believe we should consider whether that public interest, and the manner in which it is pursued, justifies any adverse effects on the disadvantaged group. . . . In the context of public education, it is quite obvious that a school board may reasonably conclude that an integrated faculty will be able to provide benefits to the student body that could not be provided by an all-white, or nearly all-white faculty.

Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District (2007)

Stevens wrote in dissent to the Court’s (5-4) decision to severely limit the school district’s race-conscious policies, which assigned students to schools with the intent of increasing racial integration. He referred to the Court’s reliance on Brown v. Board of Education (1954) as precedence for this conclusion as a “cruel irony,” and in closing wrote, “It is my firm conviction that no member of the Court that I joined in 1975 would have agreed with today’s decision.”

Sex discrimination

Cannon v. University of Chicago (1979)

Stevens wrote the majority (6-3) opinion, which held that individuals have a private right to sue to enforce Title IX. He wrote, in an opinion that is more footnote than text:

Title IX . . . sought to accomplish two . . . objectives. First, Congress wanted to avoid the use of federal resources to support discriminatory practices; second, it wanted to provide individual citizens effective protection against those practices.

Gebser v. Lago Vista (1998)

A high school teacher and student were having a secret sexual relationship; after it came to light, the teacher was fired and arrested. The student then sued the school for violation of Title IX with a claim of sexual harassment. Because the school did not know of the relationship, the Court (5-4) denied the student’s claim. Stevens’ dissent relied on his majority opinion in Cannon:

It is not clear to me why the well-settled rules of law that impose responsibility on the principal for the misconduct of its agents should not apply in this case. As a matter of policy, the Court ranks protection of the school district’s purse above the protection of immature high school students that those rules would provide. Because those students are members of the class for whose special benefit Congress enacted Title IX, that policy choice is not faithful to the intent of the policy-making branch of our Government.

Student speech

Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986)

The Court upheld (7-2) the discipline of a student who delivered a lewd speech at a high school assembly. Stevens wrote a dissent arguing that the student would not have known that the speech would warrant discipline, as previous cases had focused on the disruptive nature of speech. His point was that:

the student was probably in a better position to determine whether an audience composed of 600 of his contemporaries would be offended by the use of . . . sexual metaphor than . . . a group of judges who are at least two generations and 3,000 miles away from the scene.

Morse v. Frederick (2007)

A student was disciplined for displaying a “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” sign at a school event. The Court (5-4) determined that the school had the authority to discipline the student because the speech, although cryptic, was encouraging drug use. In dissent, Stevens wrote, “Even in high school, a rule that permits only one point of view to be expressed is less likely to produce correct answers than the open discussion of countervailing views.”

Searches of students

New Jersey v. T.L.O. (1985)

The Court upheld (6-3) a search of a high school student’s purse based on a reasonable belief that they would find evidence of possession and sale of drugs. Stevens dissented, writing that:

The schoolroom is the first opportunity most citizens have to experience the power of government. . . . The values [students] learn there, they take with them in life. One of our most cherished ideals is the one contained in the Fourth Amendment: that the government may not intrude on the personal privacy of its citizens without a warrant or compelling circumstance.

Safford v. Redding (2009)

The Court (8-1) held that the strip search of a student for ibuprofen was an unreasonable search in violation of the Fourth Amendment. Stevens wrote to make the point that “[i]t does not require a constitutional scholar to conclude that a nude search of a 13-year old child is an invasion of constitutional rights of some magnitude.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julie Underwood

Julie Underwood is the Susan Engeleiter Professor of Education Law, Policy, and Practice at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.