Simply collecting and providing data to schools is insufficient for improving teaching and learning; schools also need to gather and use multiple types of evidence to guide the work of improvement.

“Drowning in data.”

“Drowning in data.”

If you’ve had a conversation with a K-12 teacher about his or her experience as an educator in the post-NCLB era, there’s a good chance that this phrase came up in the conversation. The premise behind No Child Left Behind and the large amounts of student assessment data that resulted was the assumption that an accountability system would affect daily interaction between teachers and students through classroom-level decision making.

Instead, in the frenzy to facilitate improvement and to use the myriad types of data available, schools and districts nationwide tried to identify and implement quick solutions, such as giving teachers time to use the data in newly formed professional learning communities (PLCs). Absent clear direction on how to use data, what often has resulted is analysis paralysis: teachers and principals spending time analyzing data without a clear idea of how to use it to affect the core practice of teaching and learning — daily instruction.

Typically, school and district leaders look at student achievement data to identify students who need additional support. Then they provide resources and supports to students through pullouts, before- and after-school tutoring sessions, and in one-on-one study periods. While providing more services to address the needs of students who have not been served well in our schools is necessary to ensure student progress, providing more of the same is not likely to lead to improvements. Further, providing effective interventions is a small component of a plan for school improvement that will lead to higher achievement for all learners. Yet this approach is taken time and again, and the reason is clear: The alternative — planning, implementing, and leading an ongoing process to use data to improve classroom instruction — is one of the most difficult jobs facing education leaders.

This process requires that educators move beyond analyzing student data to collecting and employing both teacher and student evidence to inform actions. While data might represent any point of information, evidence from teachers and students can add clarity to one’s understanding of a particular challenge or strategy and assist in refining the approach.

Changing a practice that has been done one way for multiple years requires intentional instruction planning.

Empowering teachers to use data effectively as part of a process of instructional improvement calls for schools and districts to engage in the systematic collection and analysis of evidence as part of an ongoing school improvement cycle. In research and practice, I have identified four steps school leaders — supported by central office — must take in order to launch and implement this work effectively and sustain it over time to lead to improvement:

- Identify a clear instructional focus to which all teachers can align their work.

- Lead a schoolwide improvement process that facilitates ongoing learning as part of a plan, do, study, act cycle.

- Collect and analyze multiple types of evidence from teachers and students to enhance instruction.

- Build a strong team to lead the work of improvement in professional learning communities schoolwide.

Identify an instructional focus

Whether called an instructional focus or an instructional goal, schools must choose one specific area to guide the school’s work to improve instruction. This same goal will guide teachers’ work across grade levels and departments in their own professional learning communities (Dufour et al., 2004; Stoll & Louis, 2007). The focus area should be selected based on a triangulation of evidence from multiple sources of teacher and student data and should address an identified area of student need. Boudett and colleagues refer to the identified student need as the learner-centered problem (2005). Once the learner-centered problem is identified, a goal to guide teachers’ efforts to change their instructional practice crystallizes the work that is to be done. This goal should be written as: “All teachers will . . .” The work of instructional improvement can’t be effective if it’s assigned only to the special education teacher or to the math intervention teacher. To address student needs in the instructional goal area, all teachers and all leaders need to learn how to improve instruction in this area and observe it in the classroom.

What might an effective instructional goal look like?

- All teachers will provide scaffolding to students to assist them in solving complex multistep problems independently.

- All teachers will provide frequent opportunities for students to engage in student-to-student discourse on content-specific topics.

The instructional goal should be narrow enough to clarify what the school is working on but broad enough to allow differentiation at each grade level and subject area. Most important, the goal should meet the school’s larger goals for improving student learning and would focus on the knowledge and skills that the school wants students to have.

Changing a practice that has been done one way for multiple years requires intentional instructional planning. And, as with any new skill, multiple attempts are required to ensure that it has the intended positive effect on student learning. For this reason, professional learning designed to enhance teacher and leader knowledge of the focus area is essential.

Lead a schoolwide improvement cycle

Many school districts require school teams to draft complicated school improvement documents that focus school leaders’ energies on filling in boxes, reinforcing the traditional role of central office as a compliance-oriented organization. A clear school improvement plan that specifically requires the articulation of what school leaders will do to facilitate improvement and how teachers and other staff members will be engaged in the improvement process can provide a roadmap to staff and community about the school’s goals and next steps for improvement.

At a very basic level, the key components of an effective school improvement process include plan, do, study, and act.

Furthermore, central office supervisors most effectively can develop principals’ instructional leadership skills to implement this plan when they prioritize student achievement, classroom instruction, and school improvement in their work with principals and in the learning opportunities they organize (Corcoran et al., 2013; Honig et al., 2010; Honig & Rainey, 2014; Jerald, 2012).

There are a multitude of school improvement cycles and processes; some are written by individual school districts to meet their particular needs, and others are designed and widely distributed in publication. At a very basic level, the key components of an effective school improvement process include plan, do, study, and act:

Plan. Identify student need; gather teacher and student evidence to better understand the need; craft an instructional focus; and engage in professional learning to improve teacher and leader knowledge and skills in this area.

Do. Implement a change in teacher practice intended to improve student learning in the area of the instructional focus.

Study. Gather teacher and student evidence to learn to what degree the instructional change is having the intended effect on students of greatest need.

Are students engaged when the strategy is used?

What do student assessments following the use of the strategy reveal about student learning?

What similarities and differences can be observed in how teachers are implementing the instructional change, and how does student performance differ as a result?

Act. Refine the instructional change to further improve student learning.

If the student need has been fully addressed, how could the instructional strategy be used in different contexts to deepen student learning?

Engaging in a full plan, do, study, act cycle, in which both teacher and student learning improves, requires significant time. I have not observed a school facilitate a cycle successfully in less than a quarter (i.e. September to November), and often a full school year is needed to complete one cycle, particularly at the initiation of this work. But no one said leading school improvement was for the faint of heart.

Use evidence to enhance instruction

While data is a term often thought of in regard to student assessment results, attendance, and graduation rates, to name a few examples, evidence encapsulates the broader array of teacher and student data that together create a strong understanding of instructional needs and facilitate planning next steps to improve instruction in all classrooms. Just as student achievement data alone will not point to the change that needs to be made in instruction, neither will classroom observation data or student formative assessment results. Multiple data types and sources of evidence must be used together to triangulate student and teacher understanding of a specific concept in order for a plan to be devised, evaluated, and refined.

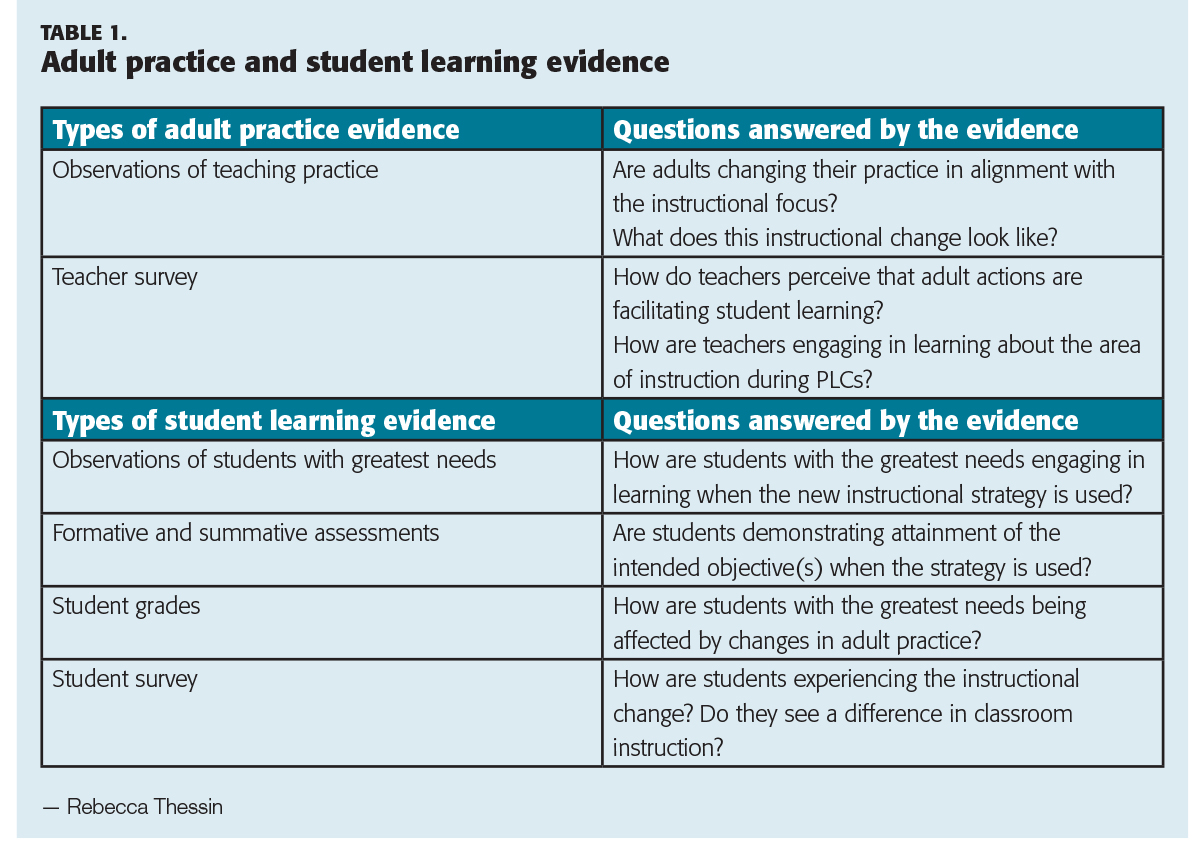

What types of evidence help a school improvement team answer critical questions about their progress on the school improvement journey? A few sample types of evidence are provided in Table 1.

Here are two key points to remember in the process of beginning a systematic plan to collect and use evidence:

- Evidence of changes in adult practice must be gathered and reviewed before determining whether adult practice is affecting student learning. If we don’t know if adults have changed their practice based on the professional learning provided, how will we know if student learning improved as a result of this work? Evidence must be reviewed and collected at regular intervals (i.e. every four to eight weeks) to shorten the evidence-to-action trajectory.

- Once the work to change teacher practice has begun, it is important to continually go back to the school’s students with the greatest needs, the school’s “focus students,” to see how they are progressing. It is also critical to gather evidence from all students to understand whether the change is helping the school meet its larger goals for students. Grades, formative assessment results, and data from student focus groups are all potential sources of data to inform understanding of how students are experiencing the change in instruction.

While school improvement plans historically have been designed to establish new goals for improvement based on annually awarded state test results, an ongoing improvement process uses evidence at each part of the cycle to immediately initiate changes in student learning to facilitate continued improvement.

Build a strong leadership team

Leading school improvement work requires that grade-level team leaders, department chairs, and team leaders all be involved in designing, implementing, and assessing the work of school improvement; one person cannot lead this work alone. To ensure progress toward achieving the instructional focus, each team leader must have the knowledge and skills to lead an effective PLC cycle by facilitating the group’s learning, creating a trusting environment in which practice can be discussed and data can be shared, and engaging the team in its own learning on the instructional area of focus. These PLCs are most effective when their work is directly aligned to the schoolwide plan, do, study, act process.

Multiple data types and sources of evidence must be used together to triangulate student and teacher understanding of a specific concept in order for a plan to be devised, evaluated, and refined.

For example, imagine that the math department is designing a lesson to incorporate a process to solve multistep problems but the science department has spent the past two weeks writing common formative assessments to assess student learning that results from a new strategy. How will leaders of the math and science PLCs work together to refine their own leadership practice, or, more important, to share findings and results schoolwide? And how would the school leader provide professional learning to prepare department leaders to lead this work when they are leading different work?

By empowering teacher leaders with the skills and knowledge to collaboratively identify the most pressing student needs, analyze evidence sources to inform the instructional focus, identify strategies to employ to change instruction, and evaluate results through PLCs, then the entire school can engage in changing instruction in every classroom, for every child. Involving all staff in collecting and analyzing evidence not only increases everyone’s data literacy but also ensures that evidence is used transparently to inform the school’s next steps to facilitate improvement.

Conclusion

When data is used as part of an ongoing improvement cycle that involves regular collection and systematic analysis of evidence, teachers can change their instructional practice to improve student achievement. To achieve this goal, the school leader must share leadership with teachers in leading a schoolwide improvement process, and central office must prioritize developing principals’ instructional leadership skills.

References

Boudett, K., City, E., & Murnane, R. (2005). Data wise: A step-by-step guide to using assessment results to improve teaching and learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Corcoran, A., Casserly, M., Price-Baugh, R., Walston, D., Hall, R., & Simon, C. (2013). Rethinking leadership: The changing role of principal supervisors. New York, NY: Wallace Foundation and Council of the Great City Schools. http://bit.ly/1KKFzL9

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R.E., & Karhanek, G. (2004). Whatever it takes: How professional learning communities respond when kids don’t learn. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Honig, M.I., Copland, M.A., Rainey, L, Lorton, J.A., & Newton, M. (2010, April). Central office transformation for districtwide teaching and learning improvement. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy.

Honig, M.I. & Rainey, L. (2014). Central office leadership in principal professional learning communities: The practice beneath the policy. Teachers College Record, 116.

Jerald, C. (2012). Leading for effective teaching: How school systems can support principal success. Seattle, WA: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Stoll, L. & Louis, K.S. (2007). Professional learning communities: Divergence, depth, and dilemmas. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press.

Citation: Thessin, R.A. (2015). Identify the best evidence for school and student improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 97 (4), 69-73.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rebecca Thessin

REBECCA A. THESSIN is an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Education and Human Development at George Washington University, Washington, D.C.