Students at 11 high-needs Kentucky high schools experienced stronger correlations between course grades and standardized test scores after their schools switched to standards-based grading practices.

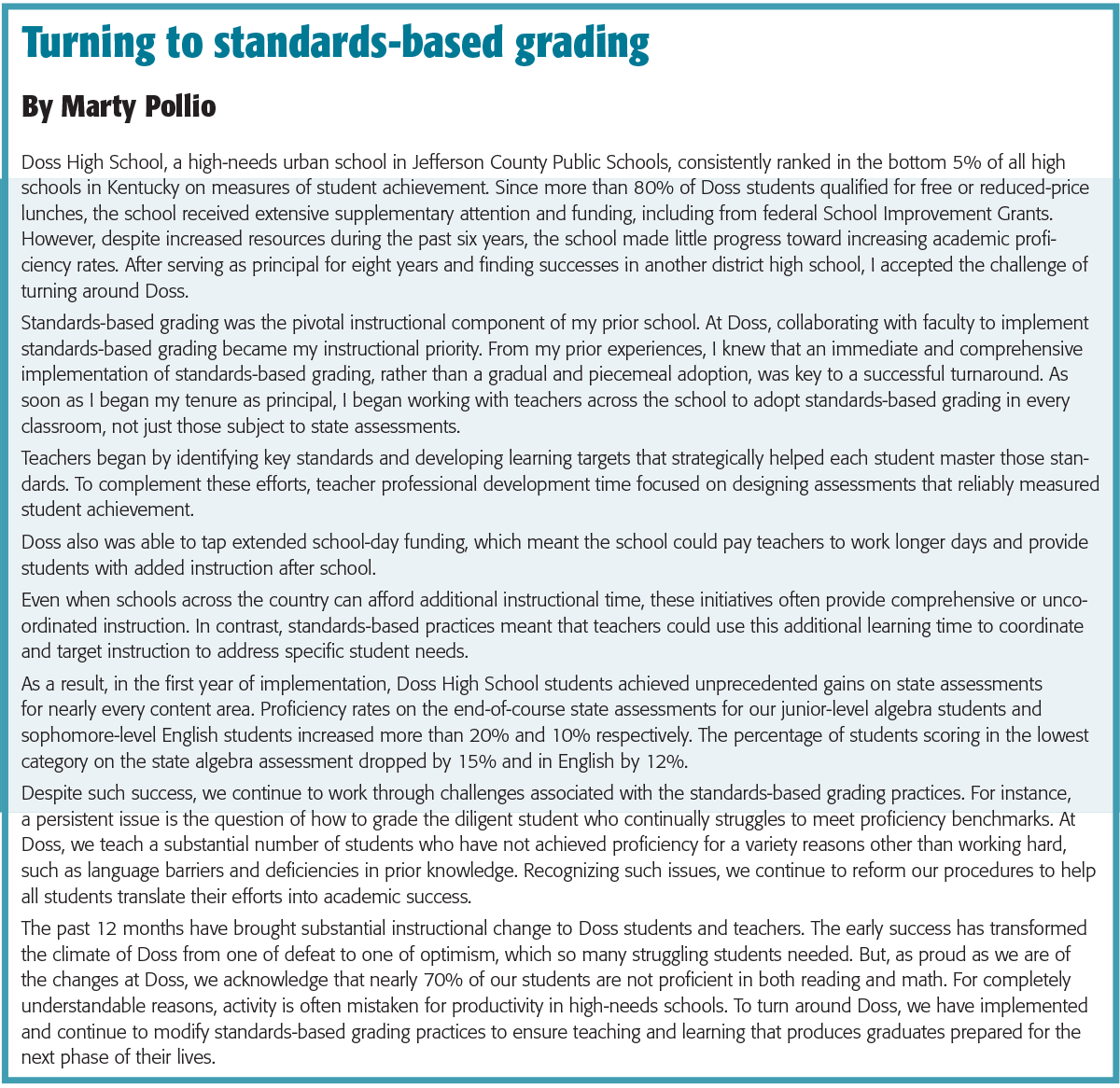

Just weeks after implementing standards-based grading practices in his Kentucky high school, Marty Pollio noticed an unintended consequence of the new initiative. He was still fielding as many parent and student grievances about classroom grades. Yet, the conversations weren’t the usual discussions about submission timeliness, participation, extra credit, and the like.

Instead of tedious debates about bookkeeping, Pollio was having meaningful dialogue with students, parents, and teachers about student learning. Instead of listening to justifications about why a student deserved an 81% instead of a 79% average, Pollio heard demonstrations about the student’s abilities to solve systems of linear equations. Similarly, rather than extra credit or bonus points, conferences focused on students’ access to additional learning opportunities and reassessments.

Although standards-based grading had enriched Pollio’s workday, questions about how or if the grading system would benefit students remained. To determine if standards-based grading benefitted students, we asked two related research questions: Does a stronger association exist between standards-based grading and standardized test scores than with traditional grading practices? Does a stronger association exist between standards-based grading and minority or disadvantaged students’ standardized test scores than with traditional grading practices?

Anecdotal, observational, and numerical evidence indicated benefits of standards-based grading. We discovered that standards-based grading practices demonstrated stronger correlations between grades and standardized test scores, including among minority and economically disadvantaged students, than traditional grading practices. These stronger relationships accompanied an increased number of students earning A’s or B’s, which resulted in more students scoring “proficient” on the state exam. Moreover, teachers said they saw advantages to the new practices.

The universal and regular reporting of classroom grades can provide timely and relevant information about aggregate and individual student performance. However, the inconsistent composition of grades (even within schools) weakens their meaning. Given the potential, variability, and influence of grades, educators should study grading practices within their classrooms, schools, and districts.

Grading matters

Changing a grading system is a dramatic change for any school, especially a high school. Classroom grades play a substantial role in the college and career trajectories of American high school students so making any changes in grades has ripples of influence. Admission to and scholarships for postsecondary institutions use grades and grade point averages. Extracurricular participation often requires that students satisfy minimum GPA requirements. Grades assigned by teachers signal students’ capabilities, as well as eligibility, to employers, admission officers, guidance counselors, principals, department chairs, parents, and students themselves.

To calculate grades, teachers must judge the performances of students. Balanced chemical equations, successfully solved word problems, grammatically correct sentences, and other demonstrations of knowledge mastery earn students points. However, in addition to their academic accomplishments, students often receive credit for speaking up in class, maintaining tidy workspaces, wearing school colors, returning signed permission slips, and donating canned goods, just to name a few.

Questioning the meaning of grades is nothing new. In 1991, Brookhart labeled grading practices a “hodgepodge” and probed their validity. Focusing on high schools, Cross and Frary (1999) warned against diluting the academic meaning of grades:

Because of the importance placed on academic grades at the secondary level, either for educational or occupational decisions, grades should communicate as objectively as possible the levels of educational attainment in the subject. To encourage anything less, in our opinion, is to distort the meaning of grades as measures of academic achievement at a time when the need for clarity of meaning is greatest (p. 56).

Since these critiques, extensive research has focused on classroom grades. Many authors have detailed grading theories or provided commentary but lacked evidence to support their claims. Among the research that has examined data and presented results, most relied on simplistic surveys that described teachers’ views and grading practices. Despite the interest in and importance of grades, few authors have rigorously examined the associations with or influences of classroom grades (Pollio & Hochbein, 2015).

Standards-based grading in JCPS

To expand and improve evidence of grading practices, we seized an opportunity presented by the implementation of standards-based grading practices at 11 high schools in Jefferson County Public Schools in Louisville, Ky. These high-needs schools faced substantial sanctions outlined by recently revised federal and state policies unless they made substantial improvements in state standardized test results. To dramatically increase the number of students meeting proficiency benchmarks, principals and teachers from the 11 high schools collaborated with district personnel to establish a competency-based instructional initiative. The teamwork between school and district-based educators resulted in Project Proficiency.

For each grading period, Project Proficiency required teachers to focus on three key standards per grading period. School and district-based content specialists derived these 18 standards from the content of the state algebra curriculum. Teachers created formative assessments that measured student progress in each standard. If a student did not demonstrate competency, teachers developed interventions that focused specifically on the student’s identified needs. Finally, schools participating in Project Proficiency adopted testing procedures that supported reassessment of students until they reached proficiency.

A final component of Project Proficiency was developing and implementing standards-based grading practices, in which students were graded solely on their mastery level in each of the key standards. Teachers no longer graded student efforts, participation, behaviors, or homework submissions. No other components factored into student grades other than demonstration of proficiency. Teachers used data from these practices to calculate grades as well as guide classroom instruction and remediation efforts.

Teachers at 11 Kentucky high schools graded students only on how well they mastered standards. They no longer graded student efforts, participation, behaviors, or homework submissions.

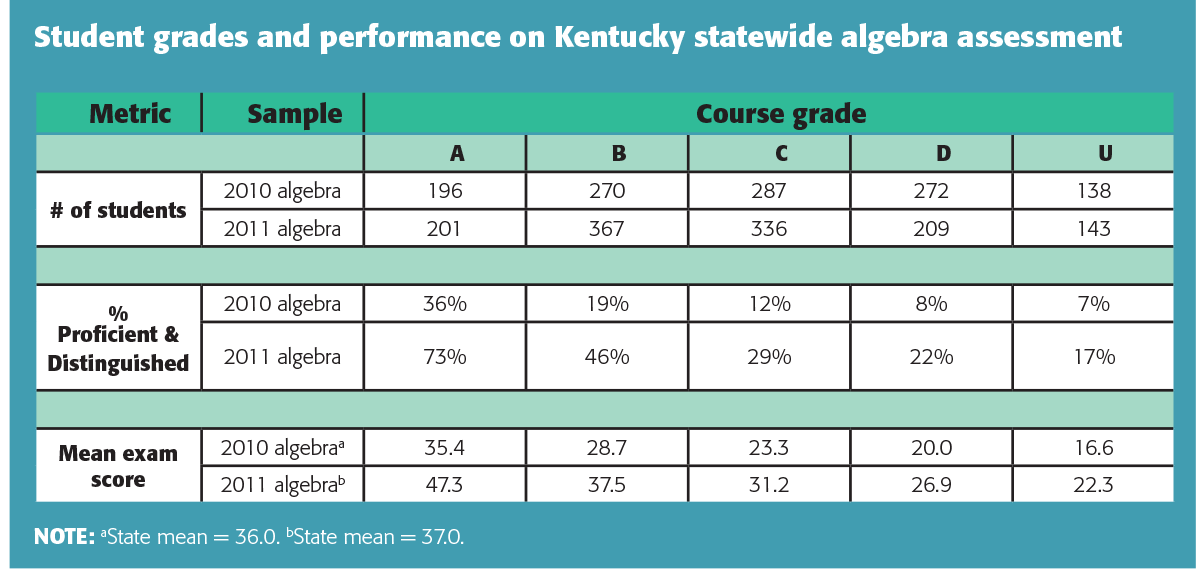

The 11 Project Proficiency high schools not only demonstrated substantial gains in math proficiency rates, but they also enabled us to compare traditional and standards-based grading approaches. Using student performance from 2010 and 2011, we studied the relationships between students’ standardized test results and grades. Specifically, we contrasted 2010 algebra results (traditional) with 2011 algebra results (standards-based). To reduce the likelihood that differences between the cohorts accounted for the findings, we also examined the 2011 science (traditional) results. Thus, we compared different students in the same subject, as well as the same students in different subjects.

Unsurprisingly, we discovered a positive but weak correlation between traditional grades and standardized test results. Thus, students with better grades tended to score better on the standardized state test. But grades did not reliably predict standardized test scores. Further disaggregation of the data demonstrated an even weaker correlation between grades and test scores of minority students.

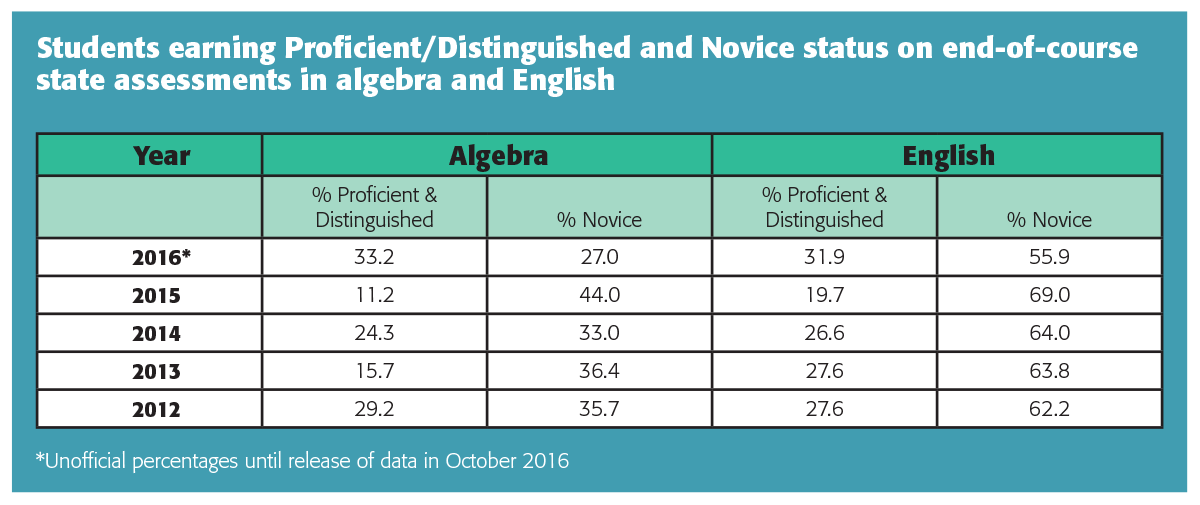

However, compared to traditional grading, standards-based grading practices demonstrated stronger correlations between grades and standardized test scores, including among minority and economically disadvantaged students. In addition, students who experienced standards-based grading more often earned A’s or B’s and scored higher on the standardized state test. Although we discovered statistical benefits to standards-based grading practices, we wondered how these differences translated into real students, grades, and test results.

In 2010, 1,163 students completed an algebra course and the standardized state test. Of the 466 students who received A’s or B’s under traditional grading practices, 26% demonstrated proficiency on the state exam, with 11 students earning the highest designation of “distinguished.” Similarly, in 2011, 1,256 students completed a science course and associated state accountability exam. Of the 514 students who received A’s or B’s under traditional grading practices, 24% demonstrated proficiency, with six students earning distinguished status.

In contrast, the exact same 1,256 students also completed an algebra course and the associated standardized state test. Of the 568 students who received A’s or B’s under standards-based grading practices, 55% demonstrated proficiency, with 22 students earning distinguished status. Not only did more students earn a higher grade, but the percentage of students passing the test more than doubled. In addition, the average test score of these A/B students exceeded the state average, which was not true of their 2010 algebra and 2011 science peers.

What led to results

Skeptics of the results might question whether these improvements contributed to or occurred because of a narrowed curriculum and “teaching to the test.” After hundreds of hours interacting with teachers, students, and parents, as well as observing classrooms, Pollio did not detect these issues in his high school. Instead, teachers reported delivering better lessons because they could focus their preparation on how to teach, not what to teach. Moreover, teachers said the specified standards supported a focus on depth of student understanding, rather than breadth of content.

Teachers reported delivering better lessons because they could focus their preparation on how to teach, not what to teach.

Although teachers perceived benefits of the new grading practices, they struggled with assigning low grades to “good” students. Teachers did not like assigning poor grades to conscientious students and feared that low marks would discourage positive behaviors. But less diligent or more disruptive students who earned high grades did not trouble teachers similarly. To reconcile such feelings, districts might implement report cards like those used by used by New York City teachers between 1920 and 1940 which provided space “for grades on effort, conduct, and personal habits” (Cuban, 1993, p. 58).

The influence and benefits of standards-based grading also can extend beyond the classroom and student. The universal use of grades provides timely information for every student. However, the confounded and variable meaning that results from traditional practices limits the ability of grades to inform decisions. Enhancing the consistency and reliability of grading practices provides opportunities to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of school performance.

For example, educators, parents, policy makers, and researchers have criticized the amount of time students spend completing standardized tests. The common practice of using interim assessments to prepare students and benchmark their performance dedicates even more time and money to standardized testing. Improved ability of grades to predict standardized test scores would reduce or eliminate the need for such benchmarking. Abolishing or reducing the use of interim assessments would not only decrease financial costs but also restore lost instructional time.

Similarly, the specificity of standards-based grading practices helps schools and district develop more efficient and beneficial interventions for students who haven’t yet achieved mastery. District and school policies typically require students to retake an entire failed course. Standards-based grading enables teachers to identify student deficiencies in specific competencies. Such identification gives them the opportunity to devise targeted remediation that does not require entire semesters and returns students more quickly to their prior academic standing.

This focus on academic competence by standards-based grading also can help reduce academic opportunity gaps. For decisions about educational opportunities, students without involved or vocal advocates experience a disadvantage. Relying on standards-based grades to make selection and participation decisions would reduce the unfair influence of a students’ social network. Reliable estimates of how well students have mastered a subject would provide a more objective tool for academic decisions.

Other considerations

Although we have demonstrated positive outcomes and possibilities of standards-based grading, educators must heed other important issues as they consider implementation. First, adopting standards in tandem with standards-based grading practices is important. In our study, central office personnel and school leaders collaborated to specify the standards of algebra. Without clear and significant standards, grades will continue to represent a hodgepodge of meaning.

Second, although standards-based grading focuses on academic competence, educators cannot ignore the multitude of expectations of schools. Collaboration, creativity, diligence, and responsibility represent just a few of the many important lessons taught and learned in classrooms. As Bowers (2009) indicated, assessment and communication of such qualities relays important information to stakeholders. Therefore, before implementing standards-based grading, teachers and administrators will want to discuss how they will teach and assess non-subject-based skills.

Third, standards-based grading is not a school improvement panacea. Implementing standards-based grading might be a necessary but insufficient initiative to improve student achievement and school performance. Although we discovered statistical and meaningful gains associated with standards-based grading, 45% of students who earned a standards-based A or B still did not score “proficient” on the state exam. But reliable assessment of students’ content mastery can serve as a critical component in coordinated efforts to effectively improve student achievement.

As district and school leaders search for reforms to improve student achievement, they should not overlook leveraging classroom grading practices. Grades are an important and ubiquitous element of high school. Yet, their hodgepodge composition creates an unreliable meaning of grades. The incomplete or inaccurate communication of grades contributes to misjudging student capabilities and mismanaging finite instructional time and resources. Standards-based grading can provide a more consistent meaning of grades, which can lead to important benefits to schools and students.

References

Bowers, A.J. (2009). Reconsidering grades as data for decision making: More than just academic knowledge. Journal of Educational Administration, 47 (5), 609-629.

Brookhart, S.M. (1991). Grading practices and validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 10 (1), 35-36.

Cross, C.H. & Frary, R.B. (1999). Hodgepodge grading: Endorsed by students and teachers alike. Applied Measurement in Education, 12 (1), 53-72.

Cuban, L. (1993). How teachers taught: Constancy and change in American classrooms, 1890-1990 (2nd ed). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Pollio, M. & Hochbein, C. (2015). The association between standards-based grading and standardized test scores in a high school reform model. Teachers College Record, 117 (11), 1-28.

Citation: Hochbein, C. & Pollio, M. (2016). Making grades more meaningful. Phi Delta Kappan, 98 (3), 49-54.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Marty Pollio

MARTY POLLIO is principal of Doss High School in Jefferson County Public Schools, Louisville, Ky.

Craig Hochbein

CRAIG HOCHBEIN is an associate professor of educational leadership at Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA.