Kappan editor Rafael Heller talks with one of the nation’s leading researchers in the field of adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

Kappan: Tell us a bit about the Guttmacher Institute and the kind of work you do there.

Lindberg: Guttmacher is a research and policy organization that focuses on sexual and reproductive health in the United States and around the world. We’ve been around for quite a while — actually, we’re celebrating our 50th anniversary this year. Our office in New York City, where I’m based, is dedicated mainly to research, and our Washington, D.C., office focuses mainly on policy. In some ways, our mission overlaps with other organizations — like SIECUS [the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the U.S.], for example, in that both organizations support high-quality sex education — but we don’t implement programs or provide services or curriculum materials. Our role is to collect accurate and reliable information and share it with policy makers and the broader public.

I’ve worked here at Guttmacher for about 14 years, conducting research on young people’s sexual behavior, their access to and use of contraception, the kinds of sex education they receive, and a range of other topics. Overall, I’ve been studying issues related to adolescent reproductive health for more than two decades. I’m a sociologist with a background in demography, which means that I tend to focus on large data sets, crunching the numbers to get a big-picture understanding of the ways in which adolescents’ behaviors and attitudes change over time.

I’ve worked here at Guttmacher for about 14 years, conducting research on young people’s sexual behavior, their access to and use of contraception, the kinds of sex education they receive, and a range of other topics. Overall, I’ve been studying issues related to adolescent reproductive health for more than two decades. I’m a sociologist with a background in demography, which means that I tend to focus on large data sets, crunching the numbers to get a big-picture understanding of the ways in which adolescents’ behaviors and attitudes change over time.

Kappan: Let’s start with the big picture, then: What stands out about the sexual behavior and experiences of today’s adolescents? How have things changed over the last 10 or 20 or 40 years?

Lindberg: Some things have changed pretty dramatically, particularly since the beginning of the HIV crisis in the mid-1980s. That was a major turning point in adolescent sexual behavior, which is no surprise because the HIV crisis marked a turning point in everybody’s sexual behavior. As a nation, we started to air a lot of conversations that used to be held in secret, if they happened at all. For example, that’s when the condoms started to come out from behind the pharmacy counter and be displayed in the aisle. And, no surprise, condom use increased a lot over the following decade.

Beginning in the 1980s, we started to see declines in the share of adolescents reporting that they had ever had sex. The rates began to plateau in the mid-2000s, and for the last dozen years the percent of adolescents who reported having sex hasn’t really changed at all. Of course, we’re still talking about a majority of the adolescent population; 3 out of 4 young people have sex during their teenage years. But that figure is significantly lower than it was in the 1980s.

Let me reiterate that I’m talking about national data here — things might look very different in your own school district or community, but the overall trend is that fewer young people are having sex now than they were a generation ago.

Another notable trend, which we’ve seen more recently, is a modest increase in the age at which people first have sex. For example, national data shows that the share of 9th graders reporting that they’ve had sex has gone down from about a third in 2001 to about 1 in 5 in 2017.

Kappan: Does that hold true for all student populations?

Lindberg: Pretty much. We don’t have data comparing urban, rural, and suburban students, but boys and girls and students of all races have been waiting longer to have sex.

The picture does get a little more complicated when you dig into the data, though. For instance, boys report having sex for the first time at a slightly younger age than girls, and Black boys slightly earlier than White boys. By age 17, however, the rates generally even out, with no differences by population.

Kappan: What about adolescents’ access to and use of contraceptives? Has that changed in significant ways?

Lindberg: We have good news about contraceptives, and the data is very solid on this issue. For example, adolescents have become more likely to use contraception the first time they have sex, which is a good predictor that they’ll continue to use contraception over time.

We’ve also seen steady increases in the use of effective contraceptive methods by adolescents. Condoms remain the most commonly used method — about 95% of adolescents who have had sex have used a condom at least once. And the pill is still very common, too, but we’re also seeing more use of long-acting, reversible methods, such as the IUD and contraceptive injections. The availability of both has become much more widespread, and while the medical community had some concerns in the past about their use by younger women, this has changed and it has become clear that those methods pose no significant health risks.

That said, what’s most important is that all young people have access to a contraceptive method that meets their particular needs. And many young people don’t. Some methods require a prescription, for instance, or interaction with a health care provider, which is much more costly without health insurance and much harder to access if you live in a rural area with no providers nearby. Young people also have a lot of concerns about confidentiality, which is a major issue especially for those who are on their parents’ health plan. In one recent study, teenage girls were asked whether they would be less likely to go to for sexual or reproductive health care if there was a chance that their parents might find out. Among those ages 15-17, 18% said they would not get this care.

At the same time, it appears that young people are becoming more likely than in the past to involve their parents in their contraceptive and reproductive health care. It’s not as sensitive a conversation as it used to be. The numbers are still small, but many of them say they go to their parents for this kind of information. Plus, there’s evidence that when young people feel that they understand their parents’ values about sex, it affects their own behaviors. Parents can and should be a big influence on their teens.

Kappan: It’s often reported that rates of teen pregnancy have declined, too. Is this because fewer young people are having sex, because they’re using more effective contraception, or because of a combination of factors?

Lindberg: Well the rates certainly have dropped, falling about one-third since their peak in 1990, and this is true for adolescent girls of all ages, all races and ethnic groups, and in every part of the county. The evidence is clear that most of the decline in teen pregnancy is associated with improved contraceptive use. But it’s not clear why teens have become better contraceptive users.

We started seeing a particularly rapid decline in teen pregnancy around the same time the recession hit, in 2008. So one theory was that adolescents were becoming really worried about the future, which led them to make the rational decision to avoid getting pregnant. But then the recession cleared up, the job market improved, and teen pregnancy rates continued to decline — so maybe it doesn’t have to do with economics after all. Then again, maybe teens are choosing not to get pregnant because they know that to get a decent job, they’ll need to focus on graduating from high school and getting some college education. My guess it that it’s some combination of these things, but we just don’t know for sure.

Also, keep in mind that it’s not just sex and pregnancy that adolescents are choosing to delay. Whatever’s happening is part of a broader cultural shift to ramping up more slowly into adulthood. For instance, the share of teenagers who are getting their driver’s license is declining. Substance use is down. Young teens are spending more time hanging out with their parents. . .

Kappan: But even though fewer teens are having sex and getting pregnant, isn’t the incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) on the rise?

Lindberg: It’s a mixed bag. On one hand, the HPV vaccine has proven to be extremely effective, which has led to declines in HPV infection. We’re still not doing enough to make sure that all young people, especially boys, get the vaccine — or get the full course of three shots — but the trend has been promising overall. On the other hand, we’ve also seen recent increases in gonorrhea and chlamydia among young people. We don’t know why those STIs are increasing, though. For instance, we haven’t seen a notable drop in condom use. Nor have I seen any indication that young people are having more sex partners than in the past. In fact, they’re having fewer partners, and they’ve become more likely to say that they’re in a serious relationship. It does seem to be that given that HIV is no longer the death sentence that it used to be, there’s been a rise of unprotected sex among young men who have sex with other men. But we always need to be careful in thinking about whether STIs have actually become more prevalent or whether people are getting tested and diagnosed more often.

What’s most important is that all young people have access to a contraceptive method that meets their particular needs. And many of them don’t.

Kappan: What about the public perception that young people’s sexual behavior is out of control on social media and the internet? Are you alarmed by recent trends, or has this so-called epidemic been overhyped as well?

Lindberg: Here, too, the evidence is murky. We do know, for example, that roughly 20% of adolescents say they’ve sent or received explicit images electronically, often photos they’ve taken of themselves. And there are certainly some reasons to be concerned about this, especially when it comes to kids’ privacy and matters of consent.

At the same time, though, it’s not at all clear that this has had a serious impact on young people’s health or social development, and it’s easy to overreact to this sort of thing. When it comes to adolescents and sex, every generation of adults engages in some form of moral panic. Don’t forget that when Elvis Presley started shaking his hips, a lot of people thought the end-time was near.

Kappan: But some would argue that online pornography truly is something new under the sun. Isn’t there something fundamentally different about the kinds and amount of sexual content that this generation sees?

Lindberg: Sure. As I like to tell my friends who are raising young kids, “Your husband looked at pornography. Your father probably looked at pornography. But this is not your dad’s pornography.” The range and immediacy of what’s available is totally different from what we experienced back in the day when your brother might have hidden a Playboy magazine under the bed.

But look, my response is that this is precisely why we need to be providing comprehensive, high-quality sex education to young people. If we don’t, then they’ll fill in the gaps with what they find online. In the old days, they might have turned to a friend for information, which wasn’t always great. Now they’ll just go to the internet.

Kappan: It looks like we’ve arrived at the topic of sex education. . . So can you tell me, in a nutshell, what’s the status and quality of sex ed in the public schools today, and how does it compare with the sex ed offered in past decades?

Lindberg: Right now, two competing trends are in play. First, I would say that where schools are providing comprehensive sex education, they’re doing a better job than in the past. Nowadays, teachers aren’t as likely to make it up as they go along, or to hand out worksheets they made up. There’s a new emphasis on using programs and materials that have been carefully designed and vetted, and that are based on evidence about behavior change. Plus, many schools and communities have decided, appropriately, to broaden the scope of their sex education programs to focus not just on how to prevent pregnancy but on a whole range of topics: reproductive health, communication between partners, body image and self-esteem, gender identity, sexual orientation, sexual assault, consent. . . So I think that among educators who provide this kind of sex education (which I’m distinguishing from abstinence-only instruction), there has been an improvement both in the quality of sex ed programs and in the range of issues that they address.

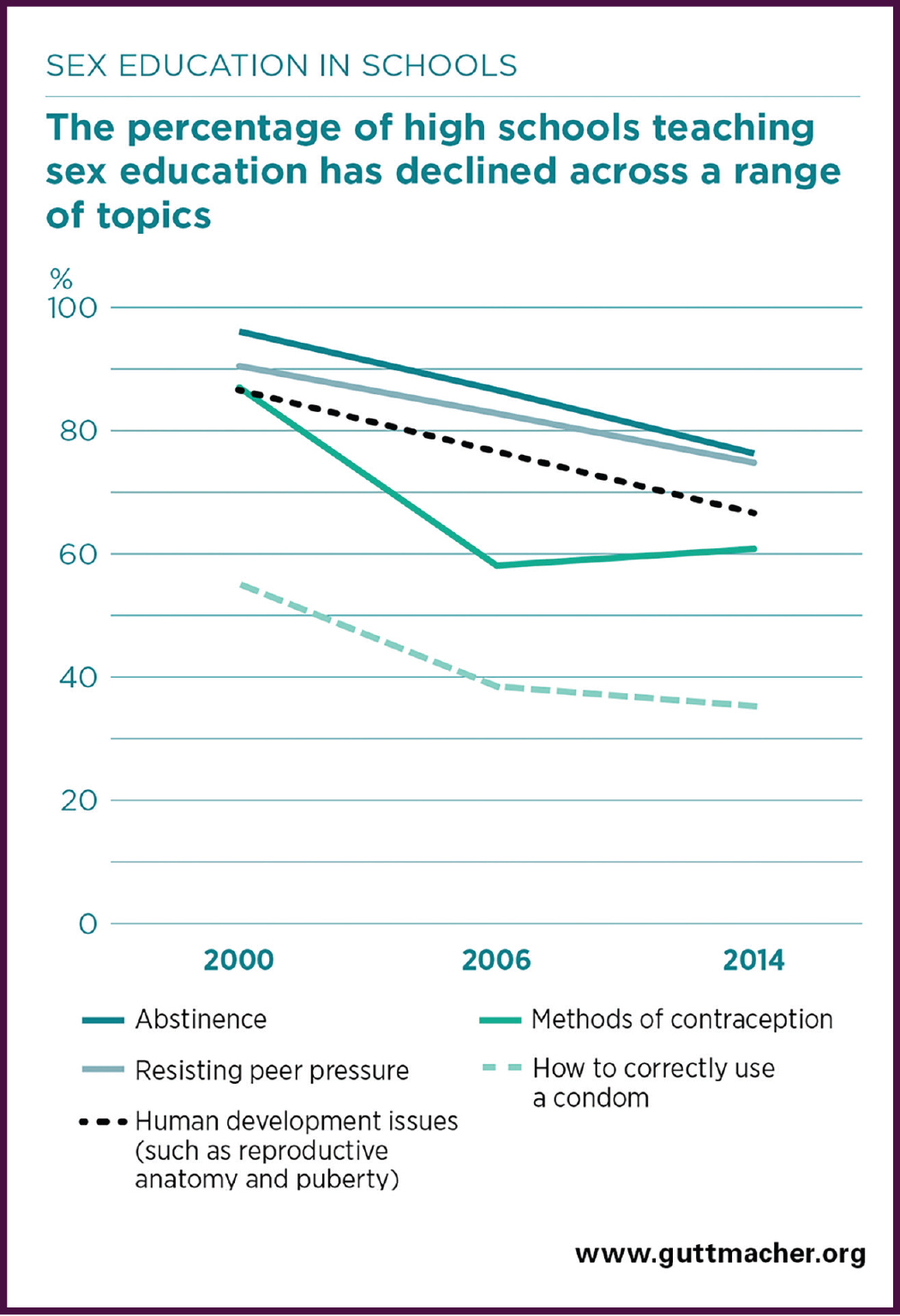

However, if you look at the big picture, it’s hard to deny that there’s been a measurable pullback from sex education in much of the country. Compared to a decade or two ago, many fewer school districts are requiring sex education, and fewer adolescents are saying that they have ever received sex education. Moreover, those who say they have received sex ed have become more and more likely to say they’re received instruction on “saying no” to sex, and less likely to say they’ve been taught about birth control methods. Nowadays, 90% of students who have sex ed in school say that they were taught to abstain from sex, or to wait until marriage, but they’re not necessarily learning about the various birth control methods that are available, or how to use them effectively. Far more kids say they learned about birth control in general than say they learned specific skills such as how to put on a condom.

It’s important to point out, also, that the biggest declines in sex education have happened in the elementary grades. Effective sex education requires a lot more than a single conversation, or even a single course. Rather, it ought to start in the early grades — in developmentally appropriate ways, of course — and then continue, becoming gradually more sophisticated, over the middle and high school years. Unfortunately, though, it has been pushed out of the elementary curriculum almost entirely. In 2000, for example, 40% of public elementary schools required teaching students about abstinence and/or resisting peer pressure. In 2014, just 6% or 7% did so.

We also see that school districts are providing less professional development related to teaching sex ed. That’s especially true at the elementary level, where you’re pulling your full-time classroom instructor out to get that training. But even in high school, people are being assigned to teach sex ed more often than they’re being trained to do it well. And, of course, sex ed is going to be more effective if you provide training, rather than just assigning it to whoever got the short straw. You want your teachers to be comfortable with these topics, and you can’t assume that just because someone can teach biology they’ll have the skill level to teach this content.

Kappan: What’s behind these declines in the number of schools providing sex ed and professional development to teach it?

Lindberg: In a lot of cases, I think that the culprit is high-stakes testing. Sex ed has been pushed out of the curriculum in much the same way that art, music, and social studies have been pushed out. It doesn’t help raise test scores, and it gets cut.

So that’s one piece of it. Meanwhile, at the federal level, the Trump administration is working actively to shift funding streams from programs that teach about contraception and other topics to ones that focus only on abstinence.

Kappan: Is there any evidence that abstinence-only programs are effective?

Lindberg: The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine is one of a number of leading national medical organizations that recently put out a position paper on this topic. They’ve concluded that the evidence clearly shows that abstinence-only programs are not just ineffective but can actually have negative consequences for young people. At the same time, the bulk of the evidence suggests that more comprehensive programs do tend to be effective at promoting adolescent health and well-being — and there’s no evidence that providing young people with information about sex or contraception leads them to engage in risky behaviors (which is what critics of sex ed tend to be most anxious about).

The most obvious problem with abstinence-only education is that it fails at its primary goal — young people don’t stay abstinent. But there’s another issue that is just as important, even if it’s harder to measure, which is that many programs stigmatize and shame young people who have sex, or who are coerced to have sex, or whose sexuality doesn’t match the teacher’s sense of what’s “normal.” So kids often feel pushed out, rejected, and attacked by these programs. When a teacher says, for example, that if you have sex you’re like a used piece of chewing gum, or a dirty sponge, that can be pretty harmful.

Kappan: Looking toward the future, what concerns you about where sex education is going, and what makes you optimistic?

Lindberg: One concern is that more and more schools are choosing to outsource sex education to community programs, many of which teach abstinence only. Second, it concerns me that the abstinence-only movement has been updating its language to make its ideas seem more mainstream and acceptable. Instead of hearing “abstinence only,” we’re beginning to hear more about “sexual risk avoidance,” for example. But it’s a case of the wolf dressing up in sheep’s clothing. Whatever you call them, programs that focus on shame and fear, without providing the information young people actually need, are harmful.

More optimistically, I think a lot of people are beginning to understand that adolescents can’t Google their way to good sexual and reproductive health. The internet and digital media can certainly be valuable tools, but we can’t rely only on them to provide high-quality sex ed. So I’m hopeful that more and more school districts will realize that their students are depending on them to provide this sort of instruction, and that their teachers will need training and resources to do so effectively.

Citation: Heller, R. (2018). Trends in adolescent sexual behavior, health, and education: A conversation with Laura Lindberg. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (2), 35-39.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rafael Heller

Rafael Heller is the former editor-in-chief of Kappan magazine.