Three New Jersey districts show how local education leaders can combat the differences in access to educational opportunities and outcomes that come along with segregation.

In 2018, a coalition of civil rights groups in New Jersey filed a lawsuit demanding the state develop a plan to desegregate all public schools. The suit argues that New Jersey state laws institutionalize segregation by requiring children to attend schools in local municipalities that are themselves highly segregated. Potential remedies called for in the suit include enabling students to enroll in schools across municipal lines and requiring the state to develop a comprehensive plan to integrate schools.

Segregation in New Jersey (as in other parts of the country) has gotten worse for many students in recent decades. Between 1989 and 2015, the percentage of New Jersey students in intensely segregated schools (schools with a student population where no more than 10% of the students are White) nearly doubled from 11% to 20%, and the proportion of schools serving a majority non-White student population more than doubled from 22% to 46%. Facts like these contribute to New Jersey’s designation as the sixth most segregated state for Black students and the seventh most segregated for Latinx students (Orfield et al., 2017).

These developments reflect a convergence of factors that include segregation and discrimination in housing, employment, and economic opportunities mixed with a growing percentage of Latinx and Asian students and declining proportions of Black and White students. In New Jersey and other states, these factors contribute to different patterns of segregation and wildly different student populations in many school districts. For example, the city of Passaic, 15 miles northwest of Manhattan, where more than 90% of students are Latinx and eligible for free and reduced-price lunch, meets the definition of an “intensely segregated school district.” In Freehold Regional High School District (RHSD), however, located in Central New Jersey, the segregation goes in the opposite direction, as almost 85% of the students are White and only about 5% are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch. In West Windsor-Plainsboro, 20 miles to the west, large numbers of Asian families, many immigrants from India and China, have come to the area for relatively high-paying pharmaceutical and technology jobs; as a result, roughly 65% of the district’s student population is Asian, about 25% are White, barely 10% are Black or Latinx, and only a small fraction are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch.

These variations create different opportunities and challenges for combating the inequitable educational opportunities and outcomes that come along with racial and economic segregation. That means that intensely segregated districts like Passaic often strive to put in place advanced programs and courses that can help their students get access to the scholarships, colleges, and careers that are more readily available in wealthier communities. But New Jersey’s segregation also means that districts like Freehold RHSD and West Windsor-Plainsboro have smaller groups of students, often Black students and Latinx students, who have much more limited access to their own district’s advanced courses and educational opportunities than their White and Asian peers.

Given these complex patterns, even with reports that the current administration of Gov. Phil Murphy (who took office after the suit was filed) may seek to settle the case, any improvements in desegregation in New Jersey will likely take years to emerge. Nonetheless, district leaders do not have to sit on the sidelines waiting for that day to come. Leaders in districts like Passaic can work to create educational opportunities that match those outside their boundaries, while districts like Freehold RHSD and West Windsor-Plainsboro can work to level the playing field within their own communities. In the process, these districts can create more equitable educational opportunities right now while recognizing the continuing commitment that creating more equitable outcomes demands.

Articulating equity goals

Passaic, Freehold RHSD, and West Windsor-Plainsboro are part of the New Jersey Network of Superintendents. Larry Leverett and Scott Thompson of the Panasonic Foundation launched the network with a founding group of 14 superintendents and a design and documentation team of which we have been longtime members. The network seeks to support superintendents (and, more recently, some of their district colleagues) in developing systemic approaches to achieving more equitable educational outcomes for all students in their districts (Hatch & Roegman, 2017).

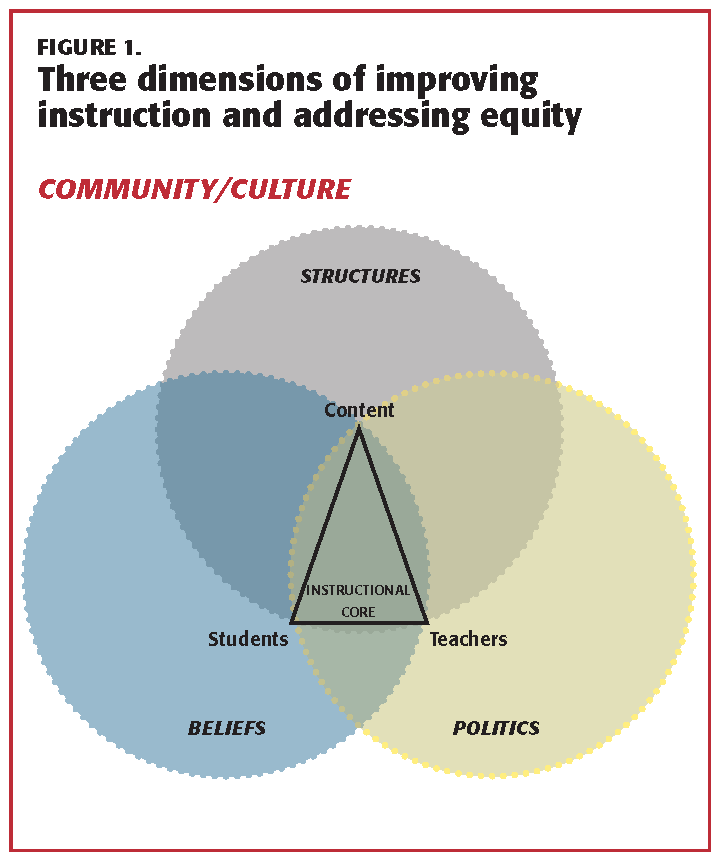

The network began in 2008 with the premise that significant improvements in student learning depend on changes in the “instructional core” — the relationship between students, teachers, and content (City, et al. 2009; Cohen & Ball, 1999; Elmore, 2002). But we’ve learned that focusing on instruction is never sufficient for dealing with the effects of segregation. As a result, for the last several years, network members have been developing a multidimensional solution that also takes into account the technical, political, and normative issues that determine which students gain access to the best curriculum and teachers (see Figure 1).

Research on tracking (Oakes, 1992; Welner & Oakes, 2007) demonstrates that initiatives to create more equitable access often fail because they concentrate on changing “technical” aspects of schooling (such as organizational structures and resource allocation), but neglect to take into account political and normative issues. For example, efforts to make technical changes by re-allocating funding to establish special programs or eliminating requirements for advanced courses can create resistance and political pressure that can block those changes (Gilens, 2005; Posey-Maddox, 2014). Technical efforts to eliminate lower-level courses also frequently ignore normative concerns, such as teachers’ and administrators’ low expectations for students from different racial and cultural groups (Cooper, 2009; Riehl, 2005).

As a first step in this multidimensional approach, districts like Passaic, Freehold RHSD, and West Windsor-Plainsboro have identified high-leverage equity goals that have a clear link to the development of more equitable outcomes, can bring about measurable improvements in relatively short periods of time, and provide a foundation for further systemic improvements over time. A powerful equity goal might, for example, address the all-too-common underrepresentation of students of color in higher-level classes (Kolluri, 2018; Roegman & Hatch, 2016).

Robert Peterkin, former director of Harvard’s Urban Superintendents Program and a member of the New Jersey Network of Superintendents’ leadership team, frequently quotes Ron Edmonds (1979) when he points out that equity goals often reflect problems that result from a failure to halt long-standing ineffective practices that restrict learning opportunities for students from underserved groups. Redressing these persistent failures is a way to make relatively quick progress in areas that are largely under districts’ control. Thus, in each of these three districts, their work began with changes in course offerings and in criteria for entrance to higher-level courses while they also worked over time to strengthen instruction.

In Passaic, when Pablo Muñoz was hired as superintendent in 2013, he and his colleagues were struck by the fact that the majority of their graduates had to spend their limited funds (whether personal or grant funds) on non-credit-bearing remedial courses if they wanted to enroll in college. Muñoz and Assistant Superintendent Rachel Goldberg saw the remedial courses as a part of the set of hurdles that Passaic’s largely Latinx student population has to overcome to enroll in and succeed in college — hurdles that their peers in more advantaged districts usually do not have to face.

Therefore, Muñoz, Goldberg, and their colleagues established an equity goal of enabling all students to graduate high school with 15 college credits and/or a career certification. As a first step in that initiative, the district identified a slew of requirements that kept many students from gaining access to Advanced Placement (AP) and other courses that could lead to college credit. “Historically,” Goldberg explained, “these prerequisites automatically took out of consideration the large number of students who were not already in an honors class and whittled the eligible pool down to tiny groups of students.” For example, prerequisites for an honors course might have required students to first take two or three related courses (and to get a B+ in some and an A- in others) and to get a teacher’s recommendation; and then students still had to have a high enough grade in the honors class and a teacher’s recommendation to get into a related AP class. Lacking evidence that those prerequisites were helpful in identifying qualified students, the district’s first steps included streamlining and systemizing the course sequences and prerequisites, increasing the graduation requirements from 120 credits to 150 credits, and changing the daily high school schedule from eight periods to nine periods.

A number of steps to strengthen instruction accompanied these changes. First, the district increased its capacity to identify students who either needed additional help or were already on track for college entrance by requiring many students to take the PSAT and SAT and the Accuplacer test (a placement test many local community colleges use to determine which students need remediation). Second, the district added a number of advanced courses (such as AP courses) and support courses (such as SAT prep courses) to better serve a broad range of students. Third, the district enhanced after-school, weekend, and summer school programs, with some offering college credit through partnerships with local community colleges. Fourth, the district substantially increased opportunities for teachers to participate in professional development related to the advanced and support courses. The district funded these changes by replacing courses with low enrollments, ensuring all teachers taught a full courseload, and pursuing grants for some of the initiatives.

Districts can create more equitable educational opportunities right now while recognizing the continuing commitment that creating more equitable outcomes demands.

In predominantly White Freehold RHSD, Superintendent Charles Sampson and colleagues examined course-taking patterns and found that students receiving special education supports and Black and Latinx students often moved from higher-level courses in 9th grade to lower-level courses in 10th and 11th grades. In response, they established an equity goal to reduce the “deceleration rates” in science and math among these students. To meet this goal, Sampson and colleagues made key structural changes, including eliminating the lowest-level courses and adding some courses targeted to help keep all students on track. For example, the district established a math “workshop” course in 9th grade to address the needs of students who would have been in the lowest-level math class. These students essentially got a “double dose” of math by taking the workshop class and the regular 9th-grade math class at the same time. To ensure the changes were effective, the district reviewed students’ progress in these new courses and offered after-school tutoring for those needing assistance. The district also created additional math-related courses in areas like computer science to encourage students to keep progressing into higher-level courses.

To strengthen instruction, the Freehold RHSD directly acknowledged the concerns teachers had about teaching more heterogeneous courses and substantially increased related professional development opportunities. As Sampson said, “We understand this is a different paradigm for you as a teacher. We understand that you have a higher percentage of kids with some really significant needs in your classroom that you might not be used to addressing. We understand that from a curriculum and a planning standpoint you need more help.” Teacher support included more time for math teachers and special education teachers to work together; in-class coaching for the teachers leading the new workshop course, and more professional development for math teachers at every level to support deeper learning through real-world examples, student-centered learning, and differentiation.

In West Windsor-Plainsboro, Superintendent David Aderhold and his colleagues recognized that Latinx and Black students were underrepresented in higher-level classes. After determining that students entering the district’s accelerated mathematics program in 4th grade were most likely to take advanced courses in middle and high school, the district adopted an equity goal to reduce the number of students in the “basic skills” (lower-level) classes in elementary schools and increase the number of students in the accelerated math class. The district moved the first year of the accelerated math program from 4th to 6th grade to give students more time to build their math skills, and they developed more objective criteria for placement into the “basic skills” math class.

Hand in hand with those changes in criteria, the district strengthened instruction by developing a math workshop model that drew on the work of Jo Boaler (2015) as well as West Windsor-Plainsboro’s own experiences with the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. To make that instructional model work with as many students as possible, Aderhold and colleagues also made a significant change to the elementary schedule by creating “family groups” that brought together teachers and students from two or three classes in shared periods. This allowed the district to schedule all kinds of special services — for occupational and physical therapy, speech, reading intervention, English as a second language, and basic skills — at the same time for students across those classrooms. As a result, Aderhold noted, “the students actually get more targeted support from the classroom teacher, with push-in support services from a basic skills interventionist, with the same ability to pull all of them together if needed.”

Taking politics into account

The superintendents had the authority to make many of these technical changes themselves, without input from school board members or other local officials. But they opted for a more inclusive decision-making process that took into account the political, economic, and cultural dynamics that come with New Jersey’s segregation. In Passaic, Muñoz worked particularly closely with the board to build broad-based political support. “We haven’t had large groups of parents questioning policy or programs or personnel decisions,” Muñoz explained. Instead, in the urban districts like Passaic where he’s worked, with largely Latinx populations, the primary political battles have been between the board, the elected representatives, and local labor unions. Therefore, he focused on getting the board’s agreement on the district’s overall goals and a policy outlining the district’s “theory of action,” which established the purpose and rationale for the curricular changes.

Sampson also described “a tremendous amount of latitude” and political support from his board. In part, he attributed that to Freehold RHSD’s unusual configuration: Because it draws students from seven different elementary districts, Sampson said that “no one local issue ever dominates what we’re trying to do.” Even with board support, however, Sampson was still hesitant to eliminate the lower-level math and science courses. For one thing, he had to work with the superintendents of the seven sending districts to make sure that all incoming 9th-grade students were prepared for the new courses. He was also concerned about the reaction of some educators in his district. As a result, Sampson eliminated lower-level courses slowly, starting with English and social studies. Moving slowly removed the fear among teachers by demonstrating that students would be supported and successful in the higher-level classes and that teachers “weren’t drawn and quartered if they struggled with new types of students.” After that, the district went on to eliminate the lowest-level courses in science and math.

In stark contrast to the experiences in Passaic and Freehold RHSD, West Windsor’s previous efforts to change entrance requirements for advanced classes in high school generated considerable controversy among parents. As a result, Aderhold and his colleagues were not surprised when a vocal group of parents objected to the changes to the accelerated math class, concerned those changes might mean less rigorous courses. However, Aderhold worked closely with the board throughout the planning and implementation of the initiative to ensure that the reasons for the changes were widely understood. In addition, Aderhold and the board built wider support by making the changes in access to high-level classes part of a popular initiative to support social and emotional learning and address the intense academic pressure that concerned many in the district.

The next level of work: Beliefs and expectations

Despite the considerable differences in racial composition and affluence that come with segregation, developing the beliefs and expectations that can support more powerful instruction for all students remains a key next step for all three districts. In Passaic, Goldberg described the elimination of the prerequisites as a key step in establishing an organizational culture that embraces the idea that the districts’ students are fully capable of meeting higher expectations. Reinforcing that culture, promoting college expectations for all students also serves as a key focus of the district’s work with staff: “Most of the work that we do to transform the district is in the development of our staff,” Muñoz reported. “Professional development, instructional rounds, the hiring and renewal of personnel, selecting the right administrators — that’s where I try to influence the movement to higher expectations.” In addition, the district has invested heavily in helping students and parents understand the college-going process and in fostering the expectation that completing college is a worthwhile and attainable goal. In addition to requiring all students to take the PSAT and the SAT, the district has provided more information about the application process and initiated partnerships with local colleges.

Sampson has also addressed the beliefs and expectations of the teachers and administrators in Freehold RHSD. To do so, the district engages building leaders, supervisors, and teachers across the district in collaborative planning and professional development around the changes in coursework. “When we roll these things out,” Sampson described, “the belief work is front and center, to the point of even modeling conversations for our supervisors to have with reluctant teachers.” At the same time, the district ramped up counseling with students to encourage them to take — and not drop — the higher-level courses, and they increased their communications with parents. Sampson reported, “We wanted to convey the message that we believed their child could perform well in more rigorous courses.”

In West Windsor-Plainsboro, Aderhold explained that many of their efforts support the development of a collective, “capability” mindset throughout the district. Rather than seeing students as having abilities that are “fixed” and treating placement in special education or lower-level classes as necessary and permanent, a capability mindset assumes that all students can develop the capacities they need to be successful. To build that mindset, Aderhold and his colleagues have also introduced all administrators to using data as a means of challenging assumptions about students’ abilities. In one instance, Aderhold invited a supervisor to present data he’d collected about underrepresentation of student groups in higher-level courses, including AP courses. “What he found there was that overwhelmingly African-American and Latinx students were not being pushed,” Aderhold noted, even though the criteria had changed. “We were having kids that met the criteria — they did very well on the PSAT for example — but they weren’t in or weren’t being pushed to take an AP class.”

The district has also launched a “Day of Dialogue” series, conversations among district educators and students about experiences and issues in the district that include topics of equity and race. “Any time that a teacher or administrator is at the table,” described Aderhold, “and the students start opening up about what they’re experiencing from their perspective, it pushes the adult. If I said the same thing, it would often be received with a block, or a hesitation. But if a student says it . . . there’s a willingness to accept the possibility that it’s real.”

Progress and challenges so far

The work in Passaic, Freehold RHSD, and West Windsor-Plainsboro demonstrates that it is possible, even in highly segregated school districts and states, to make real improvements in access to higher-level learning opportunities:

- In Passaic, the number of students taking dual enrollment (college-credit bearing) courses in high school has more than doubled from 412 in 2015-16 to more than 900 in 2017-18, andthe number of students taking at least one AP exam has gone from 94 students in 2013-14 to 707 students in 2017-18.

- In Freehold RHSD, from 2015 to 2017, there were more than 500 cases in which classified (special education) students moved into a more rigorous class. The number of students taking at least one AP exam increased from 1,540 students in 2012 to 2,658 students in 2017, despite a declining student population. During that same period, the number of Latinx students taking AP exams increased by 110%.

- In West Windsor-Plainsboro, the number of students assigned to basic skills math has been reduced by about 25%. At the same time, enrollment in 6th-grade accelerated math has increased from 76 students in 2017-18 to more than 200 students in 2018-19.

Despite these successes, continuing challenges demonstrate the intractable nature of the inequities that come with segregation. In Passaic, even as the number of students getting at least one score of three or higher on AP exams grew from 35 students in 2013-14 to 185 in 2017-18, the majority of AP test takers are still not achieving at that level. In Freehold RHSD, as of 2017, Black and Latinx students are still most likely to “decelerate” into lower-level classes, and Asian students are the only group in which the largest percentage of students are accelerating. In West Windsor-Plainsboro, the gap persists between the number of Asian and White students and Black and Latinx students taking AP exams.

Both the accomplishments and the challenges of the work to date suggest that further progress will depend on identifying high-leverage equity goals that are at the right “grain size” — goals that are both specific enough to lead to improvements in outcomes for Black, Latinx, and other underserved students, and broad enough to act as a launching pad for further systemic efforts. To achieve those goals, districts have to sustain a relentless focus on the instructional core while also addressing the structural and organizational barriers, low expectations and beliefs, and political realities that limit their students’ possibilities for growth both inside and outside their districts. In doing so, education leaders, like the superintendents profiled in this article, need to clearly communicate the challenges and need for change to their colleagues and their communities, at the same time that they celebrate the progress they are making. That work is not easy, particularly in the political, economic, social, and cultural conditions that produce and sustain segregated states such as New Jersey. As Rachel Goldberg in Passaic puts it, “It’s just hard — it’s not easy work. It’s certainly not work that you can do and always feel joyous. We get the data and we go, ‘Oh, man. That’s not as good as I wanted it to be.’ But it’s a lot better than it used to be.”

References

Boaler, J. (2015). Mathematical mindsets: Unleashing students’ potential through creative math, inspiring messages and innovative teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

City, E.A., Elmore, R.F., Fiarman, S.E., & Teitel, L. (2009). Instructional rounds in education: A network approach to improving teaching and learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Cohen, D.K., & Ball, D.L. (1999). Instruction, capacity, and improvement. CPRE Research Report Series RR-43. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Cooper, C.W. (2009). Performing cultural work in demographically changing schools: Implications for expanding transformative leadership frameworks. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45 (5), 694-724.

Edmunds, R. (1979). Educational Leadership, 37 (1), 15-18, 20-24.

Elmore, R. (2002). Bridging the gap between standards and achievement: The imperative for professional development in education. Washington, DC: Albert Shanker Institute.

Gilens, M. (2005). Inequality and democratic responsiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69 (5), 778-796.

Hatch, T. & Roegman, R. (2017, November). Equity goals and equity visits. School Administrator.

Kolluri, S. (2018). Advanced Placement: The dual challenge of equal access and effectiveness. Review of Educational Research, 88 (5), 671-711.

Oakes, J. (1992). Can tracking research inform practice? Technical, normative, and political considerations. Educational Researcher, 21 (4), 12-21.

Orfield, G., Ee, J., & Coughlin, R. (2017). New Jersey’s segregated schools: Trends and paths forward. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles.

Posey-Maddox, L. (2014). When middle-class parents choose urban schools: Class, race, and the challenge of equity in public education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Riehl, C. (2005). Educational leadership in policy contexts that strive for equity. In N. Basica, A. Cumming, A. Datnow, K. Leithwood, & D. Livingstone (Eds.), International handbook of educational policy (pp. 421-438). Netherlands: Springer.

Roegman, R. & Hatch, T. (2016). Access, success, and equity: AP access and performance in four New Jersey districts. Phi Delta Kappan, 97 (5), 20-25.

Welner, K.G. & Oakes, J. (2007). Structuring curriculum: Technical, normative, and political considerations. In F. Michael Connelly (Ed.), The Sage handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 91-112). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Citation: Hatch, T., Roegman, R., & Allen, D. (2019). Creating equitable outcomes in a segregated state. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (5), 19-24.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

David Allen

DAVID ALLEN is an associate professor at the College of Staten Island, City University of New York.

Rachel Roegman

RACHEL ROEGMAN is an assistant professor in the Department of Education Policy, Organization, and Leadership at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Thomas Hatch

THOMAS HATCH is a professor of education and director of the National Center for Restructuring Education, Schools, and Teaching at Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY. He is the author, with Jordon Corson and Sarah Gerth van den Berg, of The Education We Need for a Future We Can’t Predict .