Are selective colleges as selective as they could be in choosing among black students for admission?

Are selective colleges as selective as they could be in choosing among black students for admission?

In July 2012, President Obama issued an executive order calling for a significant improvement in the educational outcomes of African-Americans, including by increasing college access and success for African-American students.

Significantly improving the educational outcomes of African-Americans will provide substantial benefits for our country by, among other things, increasing college completion rates, productivity, employment rates, and the number of African-American teachers. Enhanced educational outcomes lead to more productive careers, improved economic opportunity, and greater social well-being for all Americans (Obama, 2012).

The order also discussed the historical barriers African-Americans have faced and overcome to get educated, including attending substandard, segregated schools. Recent statistics support a measured optimism in this mission. African-American students have made tremendous gains in high school graduation rates, increasing to 71% (DePaoli et al., 2015); in 2014, black high school graduates were more likely to enroll in college than their white peers by 71% to 67% (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014); by the year 2022, blacks are projected to have a 26% increase in enrollment in higher education (Hussar & Bailey, 2013).

While these statistics are encouraging, significant obstacles continue to impede educational opportunity for African-Americans. They include lower academic achievement and a lack of challenging college-preparatory classes. And recently, the rising ranks of black students who are immigrants or of mixed racial heritage has begun to conflate and pose a secondary challenge to African-Americans who are descendants of slavery and Jim Crow discrimination and for whom the benefits of affirmative action were intended.

The problem in schools

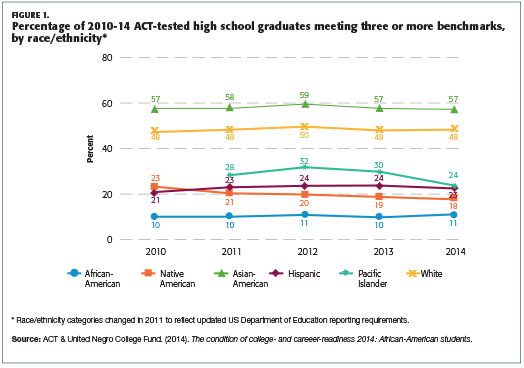

African-American high school graduates are less prepared for a college-level curriculum than any other racial or ethnic group, according to a study by ACT and the United Negro College Fund (2014). (See Figure 1.)

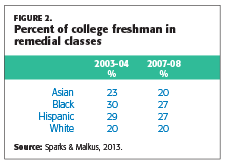

In fact, black students are more likely to take remedial courses in high school than other racial groups. The gap continues in college. (See Figure 2.)

Another obstacle to educational opportunity — the other side of the remedial courses issue — is the number of African-American students enrolling in Advanced Placement (AP) and honors courses. Taking AP courses is positively correlated with standardized test scores. Unfortunately, these courses are less likely to be offered in schools with large numbers of black and Hispanic students. Even when AP courses are offered, black and Hispanic students are disproportionately less likely to enroll in them and less likely to receive a qualifying score on the AP exam compared to white and Asian students. Presumably, black and Hispanic students are less likely to be in AP courses because they are not as academically prepared as white or Asian students. However, even when black students have strong academic skills, they are not necessarily encouraged to take AP courses. The College Board found that only 30% of black students with strong math skills took AP math, compared to 60% of Asian students (2013). Beyond the availability of AP courses, courses that simply build on foundational knowledge such as Algebra II, are not available in about 25% of high schools that serve large percentages of black and Hispanic students.

Conflation of race and ethnicity

Increasing opportunities and college access for black students typically focus on traditional barriers related to academic preparation, the racial gap in standardized test scores, and dropping out of high school. While these challenges remain, emerging challenges to college access require looking more closely at the diversity and heterogeneity within the black population as well as examining the push to make public universities more elite.

Contrary to the way they are portrayed in public discourse, black students are not a monolithic group.

One rapidly growing issue regarding higher education access and opportunities for black students involves the difference between race and ethnicity. Scholars have documented how race and ethnicity are often conflated in the literature (Cokley, 2007). An analysis of U.S. Census data shows that the number of black immigrants in the U.S. more than quadrupled between 1980 and 2013, with 8.7% of the black U.S. population being immigrants in 2013. (Anderson, 2015). That percentage is projected to nearly double by 2060. Of course, many of these black immigrants have children and grandchildren who may identify, for example, as first-, second-, or third-generation Jamaican-American or Nigerian-American, as opposed to African-Americans, whose ancestors faced slavery and Jim Crow in the U.S. With such growing ethnic and nationality diversity within the black U.S. population, an important question has arisen: Which black students should get opportunities and access, particularly regarding highly selective postsecondary institutions?

Scholars have found that foreign-born blacks are significantly over-represented in the black student populations of U.S. colleges and universities (Everett et al., 2011), particularly at the most selective institutions, where immigrants made up 40.6% of the black population in 1999 (Massey et al., 2007). Some academics have argued that such over-representation is wrong because affirmative action policies that aim to increase black student enrollment are intended to right past wrongs — particularly U.S. slavery and Jim Crow laws — in which many black immigrants and their children or grandchildren have no known family history (Rimer & Arenson, 2004; Brown & Bell, 2008). Considering the current federal constitutional basis for affirmative action policies in postsecondary education — diversity — others have suggested that racialization of foreign-born blacks in the U.S. may create unique educational barriers for them here (Mwangi & Chrystal, 2014). Unfortunately, research on black immigrants’ opportunities in postsecondary education institutions is extremely limited, probably because the federal government and colleges and universities generally do not gather disaggregated data on race, nativity, and ethnicity.

With the legal future of affirmative action unclear, understanding how to sustain and grow the still relatively small black student population in U.S. colleges and universities could become more difficult, particularly at the most selective institutions. Simultaneously, the increasing heterogeneity of the black U.S. population creates an urgent need to disaggregate this data.

Biracial and multiracial students

During the 2010-11 school year, the U.S. Department of Education began requiring colleges and universities to allow students to choose two or more races and Hispanic ethnicity on applications and other forms seeking student race and ethnicity.

President Obama’s election and biracial ancestry highlighted the postsecondary education story of multiracial Americans — most of whom, like Obama, are biracial (Pew Research Center, 2015). Yet all the attention failed to explore the question of how enrolling biracial or multiracial postsecondary students who only identify as black or African-American may affect the postsecondary education enrollment opportunities for black or African-American students. Research suggests that individuals may shift identities to take advantage of economic postsecondary education opportunities possibly made more likely by affirmative action. Antman and Duncan found some evidence that when affirmative action policies ended in certain states, students with some black or African-American racial background were 30% less likely to identify as black or African-American (2015).

The barriers to higher education, especially an elite higher education, are much more challenging for African-American students than African or Afro-Caribbean students

Before the Department of Education began requiring more race and ethnicity information, scholars such as Brown and Bell (2008) were calling for more options to ensure that black or African-American students could give a fuller picture of their self-identities on college applications — in terms of multiraciality, national ancestry, and nativity. Law professors argued this would enable selective institutions to craft affirmative action policies aimed at affirmative action’s originally anticipated beneficiaries — “[B]lacks who were descendants of those brought to the United States in chains” (Brown & Bell, 2008, p. 1281). Brown and Bell’s central argument was that multiracial students are increasingly going to displace black or African-American students in enrollment via affirmative action in selective postsecondary institutions. Generally, black immigrants and multiracial blacks fare better on socioeconomic indicators — education, income, and residential segregation — than native blacks who identify only as black (Massey et al., 2007). Of course, higher levels of education tend to lead to higher income, and higher income levels tend to lead to residing in less segregated housing. The key question, then, is why are black immigrants and multiracial blacks faring better in educational achievement? A lot of research concerning this question has been based on the work of John Ogbu, who articulated a theory that black natives, unlike black immigrants, have an oppositional culture to “acting white,” which includes educational achievement (1978). This broader cultural theory has been criticized by some who believe cultural, social, and structural forces limiting black native educational achievement are multidimensional, complex, and dynamic, just as ethnic and racial backgrounds of blacks have become (Cokley, 2014; Warikoo & Carter, 2009).

Since publication of Brown and Bell’s article, things have changed dramatically. The number of multiracial Americans has further climbed to about 7% of the U.S. population with biracial people who identify as black and white representing 11%. Furthermore, some 10% of children less than 1 year old were multiracial, and a strong plurality of those multiracial babies (36%) was biracial white and black (Pew Research Center, 2015).

However, there is one fundamental problem with that argument now: It assumes that the U.S. Supreme Court will not use the latest affirmative action case involving the University of Texas at Austin to constitutionally prohibit affirmative action. Of course, Brown and Bell’s assumption was a sensible one just after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Grutter decision and its 25-year clock, but the uncertainty of the fate of affirmative action weakens Brown and Bell’s argument. In 2003’s Grutter decision, the Supreme Court found that the University of Michigan law school’s highly individualized review of each applicant could constitutionally include race because race did not automatically dictate whether an applicant was admitted or rejected. However, the Grutter opinion indicated that affirmative action would no longer be legally necessary or sound in 25 years. Nonetheless, the fate of affirmative action is again in the balance in Fisher vs. University of Texas at Austin, just 12 years after Grutter. Thus, Brown and Bell’s argument may not be particularly relevant soon.

Conclusions and recommendations

Graduating from college can change the trajectory of one’s life and affect future earnings in ways that few other experiences can. In addition to economic effect, access to higher education directly affects health, namely mortality, especially for blacks who fare worse than other racial and ethnic groups by most health indicators. In essence, better educated people have lower morbidity rates. These economic and health indicators are closely linked to higher education opportunity and academic achievement. Most attention on barriers to higher education for black students has focused on academic preparation, standardized test scores, and high school retention. These are well-known factors with an obvious and explicit link to higher education access. Black students are disproportionately more likely to be in schools where they don’t receive the academic preparation necessary to compete for spots at competitive universities.

Many articles have been written about academically unprepared black students. A recent Atlantic Monthly article highlighted the struggles of a black first-generation college student, Nijay Williams, who like many such students was not academically prepared for the rigors of higher education (Riggs, 2014). Several reasons are given for why students like Williams are academically unprepared, including lack of access to rigorous college-prep tracks and getting academically behind early on. This is compounded by the fact that many colleges do not have resources dedicated to helping first-generation or low-income college students.

Standardized test scores have long been one of the main barriers for black students in accessing higher education, especially at elite institutions. In an effort to increase the racial and ethnic diversity of the student body, universities and colleges have used different strategies to address the over-reliance on standardized test scores. For example, Texas passed the so-called top 10% rule, which automatically admitted the top 10% of each high school graduating class to any public university. This rule was a response to Hopwood vs. the University of Texas at Austin, which banned affirmative action. Like many schools, the University of Texas at Austin needed to use affirmative action because traditional criteria like standardized test scores limited the number of accepted black and Latino students. In 2008, Wake Forest University became one of the first elite schools to discontinue requiring applicants to submit SAT or ACT scores. After that change, ethnic diversity increased by 44% between 2008 and 2014, with no difference in academic achievement between those who submitted test scores and those who didn’t (Wake Forest University, n.d.).

There are also new and emerging challenges to college access for black students. Contrary to the way they are portrayed in public discourse, black students are not a monolithic group. Not only are black students part of multiple ethnic groups, they also increasingly identify as biracial or multiracial.Data show that the educational achievements of African and Afro-Caribbean students exceed that of African-American students (Valentine, 2012), with African immigrants having the highest academic achievement in terms of achieving a college degree of all racial and ethnic groups (Page, 2007). Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates once famously said in an interview that he believed 75% of the black students attending Harvard were of African or Caribbean descent or of mixed race. These data underscore the reality that the barriers to higher education, especially an elite higher education, are much more challenging for African-American students than African or Afro-Caribbean students (Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 2006).

Few experiences can change the trajectory of one’s life and affect future earnings as a higher education.

So what can be done to address these barriers? More funding should be provided to schools with large percentages of black students to offer more AP courses. The data are clear on this: Students who take AP courses are more competitive when applying for admission to colleges and universities. In addition, remediation courses should shift from a deficit orientation and focus on at-risk students to a strengths-based orientation that emphasizes the student’s potential to learn, as discussed by Steele (1992).

Given the limitations of standardized tests, more schools should make these tests optional and instead use a more holistic set of admissions criteria. According to the National Center for Fair & Open Testing (2015), 195 top-tier schools deemphasize the SAT and ACT in admission decisions. This includes schools that exempt students from taking the SAT or ACT when they meet certain GPA or class rank criteria. It also includes schools that require the SAT or ACT only for placement purposes or to conduct research. Notable among these schools are prominent national liberal arts colleges such as Bowdoin College, Middlebury College, Smith College, and Wesleyan University, along with prominent national universities such as Wake Forest University, New York University, and the University of Texas at Austin.

Given the educational disparity between African and Afro-Caribbean immigrants and African-Americans, programs and initiatives devoted to increasing diversity should focus on African-Americans. This recommendation is not without challenges because of the fluid nature of racial and ethnic identity. For example, there can be two first-generation African immigrant students where one student identifies as Nigerian-American and, because of acculturation, the other student more strongly identifies as African-American. These scenarios cannot be avoided. Nevertheless, efforts should focus on African-Americans since they lag behind other racial and ethnic groups on most educational indicators.

There is no easy way to address the challenges posed by an increase in biracial and multiracial classification. The argument that affirmative action was originally intended for the descendants of those brought to the United States in chains would seem to address the concern that biracial or multiracial people will eventually displace black or African-American individuals. However, this argument will be moot if the Supreme Court does not rule in favor of continuing affirmative action. Until the future of affirmative action is known, schools should collect as much information about students’ self-identities as possible, including whether students identify as being biracial or multiracial. This information should be used to ensure that African-Americans are not being displaced by biracial or multiracial individuals.

It is a mixed picture regarding increasing opportunities and college access for black students. There are reasons to be optimistic, including an increase in high school graduation rates and a projected increase in college enrollment for black students. However, there are also several reasons to be concerned. Addressing only the traditional barriers to higher education is no longer sufficient given the emerging challenges related to the conflation of black ethnic groups and the increasing numbers of biracial and multiracial identification.

References

ACT & United Negro College Fund. (2014). The condition of college & career readiness 2014: African-American students. ACT.

Anderson, M. (2015). A rising share of the U.S. black population is foreign born; 9% are immigrants; and while most are from the Caribbean, Africans drive recent growth. Pew Research Center. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Antman, F. & Duncan, B. (2015). Incentives to identify: Racial identity in the age of affirmative action. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 97 (3), 710-713. www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1162/REST_a_00527

Brown, K. & Bell, J. (2008). Demise of the talented tenth: Affirmative action and the increasing underrepresentation of ascendant blacks at selective higher educational institutions. Ohio St. Law Journal, 69, 1229-1284.

Cokley, K. (2007). Critical issues in the measurement of ethnic and racial identity: A referendum on the state of the field. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 224-234.

Cokley, K. (2014). The myth of black anti-intellectualism: A true psychology of African-American students. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

College Board. (2013, February 13). The 9th annual AP report to the nation. http://bit.ly/1LQBokT

DePaoli, J.L., Fox, J.H., Ingram, E.S., Maushard, M., Bridgeland, J.M., & Balfanz, R. (2015). Building a grad nation: Progress and challenge in ending the high school dropout epidemic. Annual update, 2015.Washington, DC: America’s Promise Alliance. http://1.usa.gov/1l8qcHD

Everett, B.G., Rogers, R.G., Hummer, R.A., & Krueger, P.M. (2011). Trends in educational attainment by race/ethnicity, nativity, and sex in the United States, 1989-2005. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34 (9), 1543-1566.

Hussar, W.J. & Bailey, T.M. (2013). Projections of education statistics to 2022 (NCES 2014-051). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. (2006). Most blacks at Harvard are from high-income families. www.jbhe.com/news_views/52_harvard-blackstudents.html

Massey, D.S., Mooney, M., Torres, K.C., & Charles, C.Z. (2007). Black immigrants and black natives attending selective colleges and universities in the United States. American Journal of Education, 113 (2), 243-271.

Mwangi, G. & Chrystal, A. (2014). Complicating blackness: Black immigrants & racial positioning in U.S. higher education. Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis, 3 (2), 3.

National Center for Fair & Open Testing. (2015). 195 “Top tier” schools which deemphasize the ACT/SAT in admissions decisions per U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges Guide (2016 edition). http://bit.ly/1iDQAam

Obama, B. (2012, July 26). Executive order — White House initiative on educational excellence for African-Americans. Washington, DC: White House. http://1.usa.gov/1RWbBJs

Ogbu, J. (1978). Minority education and caste. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Page, C. (2007, March 18). Black immigrants collect most degrees, but affirmative action is losing direction. Chicago Tribune. http://trib.in/1m18FkP

Pew Research Center. (2015). Multiracial in America: Proud, diverse, and growing in numbers. Washington, DC: Author. http://pewrsr.ch/1Nt50Hm

Riggs, L. (2014, December 31). First-generation college-goers: Unprepared and behind. The Atlantic. http://theatln.tc/1LQDkda

Rimer, S. & Arenson, K.W. (2004, June 24). Top colleges take more blacks, but which ones? New York Times. http://nyti.ms/1GMnIIP

Sparks, D. & Malkus, N. (2013, January). First-year undergraduate remedial coursetaking: 1999-2000, 2003-04, 2007-08. Statistics in Brief. NCES 2013-013. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2013/2013013.pdf

Steele, C. (1992). Race and the schooling of black Americans. Atlantic Monthly, 269, 68-78. http://theatln.tc/1LQDIs0

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014). College enrollment and work activity of 2014 high school graduates. Washington, DC: Author. http://1.usa.gov/1SpSJmU

Valentine, C. (2012, September 4). Rethinking the achievement gap: Lessons from the African diaspora. Washington Post. http://wapo.st/1Wx4wpz

Wake Forest University. (n.d.). Holding standard procedure to a higher standard. Winston-Salem, NC: Author. http://admissions.wfu.edu/apply/test-optional/

Warikoo, N. & Carter, P. (2009). Cultural explanations for racial and ethnic stratification in academic achievement: A call for new and improved theory. Review of Educational Research, 79 (1), 366-394.

Citation: Cokley, K., Obaseki, V., Moran-Jackson, K., Jones, L., & Vohra-Gupta, S. (2016). College access improves for black students but for which ones? Phi Delta Kappan, 97 (5), 43-48.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Kevin Cokley

KEVIN COKLEY is director of the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis, a professor in the Department of Educational Psychology as well as the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies, University of Texas at Austin.

Karen Moran-Jackson

KAREN MORAN-JACKSON is a research associate for the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis at the University of Texas at Austin.

Leonie Jones

LEONIE JONES is an administrative associate and community outreach specialist for the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis at the University of Texas at Austin.

Shetal Vohra-Gopta

SHETAL VOHRA-GUPTA is associate director of the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis, all at the University of Texas at Austin.

Victor Obaseki

VICTOR OBASEKI is policy coordinator for the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis at the University of Texas at Austin.