The new ESSA law encourages schools to follow the practices of many other schools that have significantly raised achievement levels for low-income and minority youth. It also helps educators find schools to learn from.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) gives educators a fresh opportunity to think through how to ensure that all students achieve at high levels, especially children from low-income families and children of color. In so doing, ESSA continues the work of its progenitor, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), first passed in 1965. The original idea was that schools serving large numbers of kids living in poverty would provide those kids the same educational opportunities that white, middle-class kids had — in exchange for a large federal investment.

Fifty years later, opportunity and performance gaps remain large. That was true when the 2001 version of ESEA, No Child Left Behind, was passed as well.

But there has been more success than often acknowledged. For example, from 2000 to 2015, the percentage of students taking the National Assessment of Educational Progress exam and who scored below basic on 4th-grade math was cut in half, from 35% to 18%. Reading progress was less dramatic, but the percentage of students scoring below basic declined from 41% to 31% (NCES, 2015).

That means that many thousands more children are reading and doing math at basic levels largely because schools figured out new ways to help them. What’s more, the progress did not come at the expense of more advanced students; in fact, the percentage of students scoring proficient or advanced increased over the same period of time.

Partly for that reason, the new law continues with four principles that had been in earlier iterations, all of which have important implications for students from low-income homes and children of color:

#1. States must articulate what they expect students to learn.

ESSA not only maintains the requirement that states establish standards but explicitly requires that they be tied directly to what is required for credit-bearing classes in college, career, and technical education. As a result, educators have agreed-upon goals for students. A generation ago, educators were expected to establish their own goals, which led to different teachers having different expectations for students and was often disastrous for students of color and children living in poverty.

#2. Schools have an obligation to help all their students meet or exceed standards.

ESSA makes clear that all students should meet standards, not just college-bound students and not just middle-class students. Schools may fall short of meeting their obligation, but they are nonetheless expected to be moving toward it.

#3. States should assess regularly to measure whether schools are teaching the standards.

Teachers may know how their students are doing, but, without outside assessments, they can’t know how their students compare to other students in the state or even other students in their own schools. Students, parents, and community members also are often left completely in the dark without outside assessments. Requiring student testing in reading and math once a year from 3rd through 8th grade and once in high school, with additional requirements in science, has helped build a student achievement knowledge base.

#4. States must make information about schools, including assessment results, available to educators, students, parents, and communities.

We now have information capable of answering any number of questions. For example, we can see which schools have similar kinds of kids and which schools help students read and do math. Not only that, ESSA retains the requirement that the data show how well schools are serving all students and specific demographic groups of students. States using assessments that other states also use — PARCC, Smarter Balanced, and ACT Aspire, for example — will be able to compare their results with students and schools in other states. This new ocean of data can sometimes feel overwhelming, but, when properly used, educators and the rest of us can identify what works under what conditions with which students.

The data that has become available over the past decade has permitted us to find schools and districts that have been successful with large populations of children of color and children from low-income homes. We are only at the beginning of using that information to expose and learn from the expertise in schools and districts.

While keeping important elements of earlier iterations of the law, ESSA gives states and districts more latitude to design accountability systems for schools. What they end up doing with this new freedom will depend to a large extent on how they are able to exploit the information and data they have to forge a path that is most appropriate for their communities.

A path created by data

The problem is that the path that data point out is neither a straight shot nor an easy stroll. Over the past decade, I have visited dozens of high-performing schools with large populations of students of color and students from low-income families — I sometimes call them “unexpected schools” — and I have not seen one single thing that has helped all of them. All are amalgams of complex factors that can’t be reduced to a list of programs, policies, or practices.

But they adhere to basic principles that go to the heart of the purpose of public schools and why many educators chose the profession. The most basic: Students come to school to get smarter, and educators are responsible for figuring out how to help them. Thus, the first thing to notice in all those high-performing schools is that the educators in them believe that they can help kids get smarter.

But belief alone would be a recipe for frustration. The real job for schools is to systematically and methodically build relationships among adults and children that allow learning and then just as systematically and methodically develop the knowledge and skill of the adults.

This means that in many ways these unexpected schools stand as repudiations of all of the attempts in the last couple of decades to “teacher-proof” and even “principal-proof” schools. That is, they don’t simply adopt programs or put new practices in place. I can’t count the times the principals in these buildings have said to me, “It’s not about programs.” So what is it about?

Capturing exactly what they do is difficult, but these are some of the most significant characteristics:

#1. They incorporate what we know from research.

The last decade or so has seen the crystallization of solid research that helps educators ensure that all students learn; the high-performing schools I visited are usually conversant with the most important of the research. Sometimes the principal makes it his or her job; sometimes teachers take on the responsibility of keeping up with a segment of research and communicating it to colleagues. To live up to the expectations of ESSA, educators will have to become experts in locating and using relevant research. A few bodies of research that they often turn to are:

- Cognitive science research. For more than 100 years, cognitive scientists studied how people learn and under what conditions but didn’t bother to share their results with educators. The last 15 years have seen the unveiling of that research, some of which has important implications for educators. (For a quick cheat sheet, readThe Science of Learning, which is available on the Deans for Impact web site (www.deansforimpact.org/the_science_of_learning.html) or read “The value of knowing how students learn” in the April 2016 issue of Kappan.)

- Research on school practices that best help kids learn. Decades’ worth of educational research has been, until recently, fairly useless to the ordinary educator who couldn’tpossibly wade through all the small-scale qualitative and quantitative studies that have been done. However, a few years ago New Zealand researcher John Hattie did a meta-analysis of 800 meta-analyses that included thousands of studies. He has distilled all that research into a few insights that focus on the power of providing accurate, fast feedback to learners and the processes required to figure out what that accurate feedback should be. (For more, go to www.visible-learning.org.)

- Research on key organizational leverage points for improvement. The most powerful lever for school improvement is a knowledgeable, skillful school principal. But the principal’s role is still overlooked in many of the conversations around school improvement, which turns out to be a big mistake. (For more, go to wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center.)

Those three areas don’t exhaust the list of worthy research, but educators and policy makers who begin with a solid grounding in them will have a few ideas about where to start with their classrooms, schools, and districts. But that’s just the beginning. School people are practical, and they want to do more than simply read research. That leads to the second thing they do.

#2. They examine the experiences and practices of more successful classrooms, schools, and districts to see what might be useful to try.

This seems obvious. Although more educators are doing so, too many still consider their own schools to be so individual that they have little to learn from other schools. Every school has its own context and particularities, but kids are kids, teachers are teachers, and systems are systems. In the high-performing schools I visited, school leaders told me of the times they have led teams to other schools so they would, as one principal said, “steal every idea we could.” All teachers, principals, and superintendents can do this kind of continual inquiry. Everyone can find someone more successful in some way and learn from them. But that is still not enough.

#3. They systematically examine the experience of their own classrooms, schools, and districts to see what is successful and what is not.

Again, this seems obvious and yet the education field has not been accustomed to bringing a critical eye to internal practices. Principals might be aware that some teachers are much more successful than others, but they rarely do much to expose that expertise so that the rest of the school’s teachers can learn from them. The data and information that will continue to be collected and reported under ESSA provides an important tool for educators to look inward to expose internal expertise.

In all the high-performing schools and districts I’ve been in, the most powerful lever of improvement rests on the ability of one teacher to say to another — “My kids aren’t doing as well as yours. What are you doing?”

In all the high-performing schools and districts I’ve been in, the most powerful lever of improvement rests on the ability of one teacher to say to another: “My kids aren’t doing as well as yours. What are you doing?” Mind you, for teachers to feel comfortable enough to show that vulnerability requires a carefully built culture of trust. Moreover, for teachers to know how well their students are doing in comparison to other teachers requires them to agree on what students should know and be able to do, give the same assessments at more or less the same time, and study the results looking for patterns. That leads to the final point.

#4. They systematically examine all their systems to ensure that they work together to support teaching and learning.

Every school has some kind of system for classroom observations, handling student misbehavior, ordering supplies, scheduling time, and so on. Too often, those systems run on their own tracks without clear reference to how they affect teaching and learning. For example, schools wanting to ensure an orderly environment will suspend students for talking too much in class or mouthing off inappropriately. The effect of that, however, is to remove students from the ability to learn and teachers to teach. In the high-performing schools I have been in, the emphasis is on keeping students in class; when that is impossible, they at least try to keep them in the building. “There are things I will suspend a student for, such as fighting,” said Melissa Mitchell, principal of George Hall Elementary School in Mobile, Ala. “But we need that child here so we can teach him.” Some high-performing schools have in-school suspension where students complete work, are mentored, and available for teachers to pull them into the classroom for an essential lesson or assignment. The point is to ensure that, as Mitchell said, “discipline becomes educational, not just punishment.”

But many more systems often don’t align with teaching and learning. Consider scheduling: Building a master schedule is complicated, but far too many principals treat it simply as a logistical exercise rather than the heart and soul of teaching and learning. That’s why in many high schools students line up outside counselors’ offices during the first week or two of classes because they were assigned Algebra I although they’ve already passed Algebra II or they were put in Guitar when they wanted Computer Programming. Meanwhile, teachers and students must deal with continual additions and subtractions to their classes, undermining all attempts to teach and learn. These are the kinds of things you don’t find in the unexpected schools I have been in.

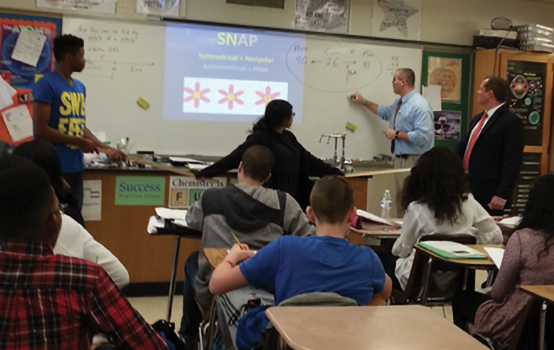

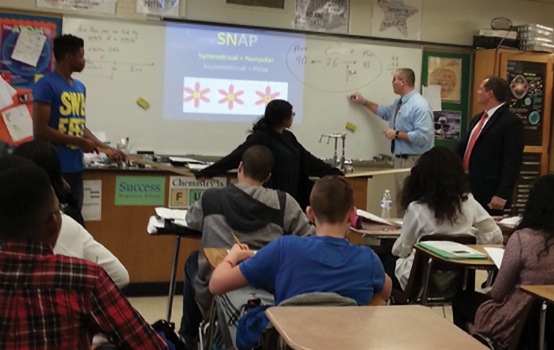

Malverne High School in Nassau County on New York’s Long Island is an example of how a school can take a good look at its current practices, learn from the research, and remake itself — exactly the sort of change that ESSA intends to encourage. Nassau County is racially and ethnically diverse, but it has a long, ugly history of discrimination and was recently called “one of the most fragmented, segregated, and unequal counties in the U.S.” (Wells et al., 2014). Malverne High School is certainly an example of segregation at work. The school serves not only the mostly white town of Malverne but the mostly African-American town of Lakeview next door. The last few years have seen a small influx of white students — drawn by the success of the school — yet most of Malverne’s white students attend private or parochial school. At Malverne High School, 60% of the students are black, 20% Hispanic, 4% Asian, and almost half of students qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

A decade ago, the school was a mess. In 2003, for example, only about 55% of students graduated with a Regents, or New York State, diploma. Since then, educators have pushed forward on a number of fronts, drawing on a great deal of research about how to build strong relationships with students and challenge them with rigorous instruction. They learned from nearby schools with similar demographics that were more successful. They identified their most successful teachers and made sure other teachers had opportunities to learn from them. They continually studied their own data to see what was working and what wasn’t. And they made sure their schedules, discipline systems, and other systems worked to support teaching and learning.

Here’s an example: They looked at their dropout data and realized that students essentially dropped out in 9th grade; they could see that freshmen who failed in the first marking period or who had high rates of absenteeism were much more likely to drop out than other students. So the high school administrators began working with the middle school to identify 8th graders who were academically or behaviorally at risk. Counselors meet with at-risk 8th graders and their families, and students attend a summer program that includes leadership training, community service (such as serving soup at a homeless shelter), and fun activities as well as academic support. “I knew we had to make it fun,” said Malverne Principal Vincent Romano. “We couldn’t require the kids to come.” The experience continues through the school year with a special class focused on helping students improve their organizational and study skills and giving them insights about how to get additional help from teachers. They also help them with anger management and navigating the social shoals of high school.

They identified teachers and staff who have the best results with struggling kids, and they ask them to share what they know with others. Dropout rates and discipline issues have been reduced to a trickle.

Not everything Malverne has done was successful. “We have a long list of things we tried that didn’t work,” Romano said. But by continually examining internal data to see what problems exist, studying research and the practices of other more successful schools, and making sure their systems work in concert with each other, Malverne has gone a long way to solving a lot of problems.

How can we tell? Last year, 93% of students graduated with a Regents diploma, 54% with an advanced designation, which indicates mastery of a curriculum that prepares students for a four-year college. This year, 70% of students are on track to graduate with an advanced designation. More than 90% of graduates go on to college, most to four-year colleges. (For context, 78% of students statewide graduate with a Regents diploma, less than one-third with advanced designation.)

And the school has seen a nice increase in passing rates on the New York State Regents Exams, which are New York’s end-of-course exams. That’s not all they talk about at Malverne; they also talk about their award-winning band, robotics team, model United Nations, and athletics.

All this because the educators at Malverne High School believed that all students could achieve at high levels and then, like engineers, worked the problem. They drew on research, the practices of nearby successful schools, and kept a close eye on their own data to identify problems and evaluate their successes and failures so they could do more of what works and less of what didn’t.

These things are easy to say, not so easy to do. Teachers, staff members, administrators, and students put in a lot of work, sometimes really difficult work. But Malverne exemplifies the basic principle that kids go to school to learn, and it is the responsibility of the professionals to teach them to figure out how to help them. No matter what the federal law is, that’s the basic contract that should not change.

References

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2015). The nation’s report card: 2015 mathematics and reading assessment. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/#?grade=4

Wells, A.S., Ready, D., Fox, L., Warner, M., Roder, A., Spence, T., Williams, E., & Wright, A. (2014). Divided we fail: The story of separate and unequal suburban schools 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University.

More information

The Education Trust, a national education advocacy organization, has developed a series of brief papers exploring the requirements and implications of the Every Student Succeeds Act, including its requirements on standards, assessments, public reporting, and accountability. They are a valuable resource to anyone who wants to know what’s in the law without having to wade through all 391 pages.

Ed Trust’s briefs can be found here: https://edtrust.org/issue/the-every-student-succeeds-act-of-2015/

To read the full bill, go here: www.ed.gov/ESSA

Citation: Chenoweth, K. (2016). ESSA offers changes that can continue learning gains. Phi Delta Kappan, 97 (8), 38-42.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Karin Chenoweth

KARIN CHENOWETH is writer-in-residence at The Education Trust and, most recently, coauthor of Getting It Done: Leading Academic Success in Unexpected Schools .