A research team identifies discriminatory trends in a choice system — and proposes how to make that system fair.

School choice, a marginal influence in most of the history of American education, has recently become a dominant force in a growing number of U.S. cities. In the case of the nation’s famous examination schools, such as New York’s Stuyvesant High School or Boston Latin School, conflict has erupted over the racial effect of standards used to select students. The allocation of scarce and valuable places in these schools is important to parents and their children, with communities of color often protesting the radical underrepresentation of students of color, and white and Asian parents objecting to admission criteria that don’t rely on tests and grades, which they define as measures of merit. In largely nonwhite city school systems where most schools are far behind national norms, the few outstanding schools become precious resources. And when black and Latino groups see most of those seats going to white and Asian students who make up a small minority in the district, there are often objections. In many cities, civil rights claims allege that the choice process discriminates against black and Latino students.

We address those struggles here, focusing on extensive research on criteria schools in Buffalo, N.Y., a case in which the federal government’s Office for Civil Rights found discrimination, negotiated an agreement with the district to commission an independent assessment, and eventually negotiated a settlement. The authors were deeply involved in that research and believe the findings are relevant to other schools of choice that use selection criteria (Orfield et al., 2015).

We will take the reader into complex and strongly contested terrain. We don’t oppose the creation of demanding special schools in urban communities and have not proposed shutting down existing schools. Our fundamental concern is with operating them fairly across lines of race, ethnicity, poverty, and immigrant status. We believe that in schools of choice, as in our most selective colleges, diversity is an asset and that many students from homes and neighborhoods with limited resources are capable of succeeding in demanding schools without any lowering of standards, if the process is managed appropriately.

Case in point: Criteria schools in Buffalo

During the 1980s, under court-ordered desegregation, Buffalo’s school district developed a highly diverse, well-integrated, and academically excellent magnet school system, which was often cited as a national model. In 1995, Buffalo Public Schools was released from court oversight. Two years later, a reverse discrimination case was filed against the district, claiming that the racial quotas being used discriminated against white students. As a result, the district’s resources, tools, and commitment to desegregation were sharply curtailed.

For the past two decades, Buffalo Public Schools’ choice system has relied on a set of criteria schools that admit students on the basis of some combination of test scores, grades, attendance, and teacher or parent recommendations. Two of the district’s eight criteria schools — City Honors and Olmsted — are especially sought after; in fact, Newsweek (2013) consistently ranks City Honors among the nation’s top 30 schools. Echoing the civil rights violations alleged against other competitive admissions schools, some Buffalo residents have raised concerns about the highly unequal representation of students from different racial groups in Buffalo Public Schools’ criteria schools.

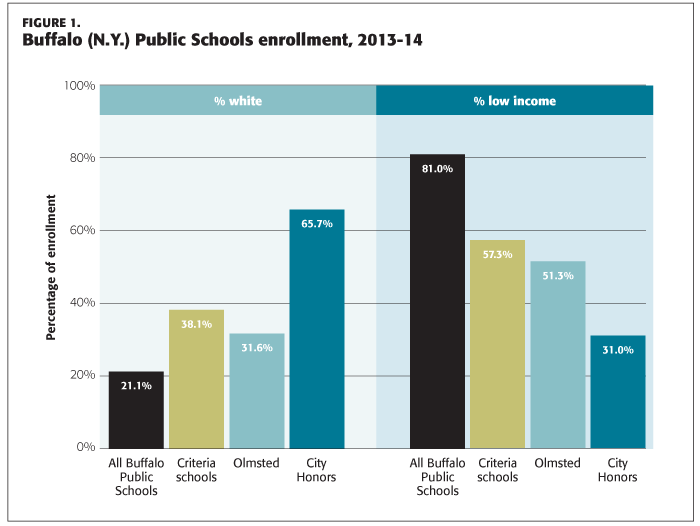

In 2014, a group of Buffalo parents filed a complaint with the federal Office for Civil Rights, claiming that black students were underrepresented in the city’s criteria schools. The office’s investigation substantiated the claim. In 2013-14, Buffalo Public Schools’ enrollment was 21% white, 54% black, 16% Latino, and 6% Asian; 81% of students were low income (see Fig. 1). However, the criteria schools enrolled disproportionately large shares of white students (38%) and small shares of low-income students (57%). The largest disparities occurred at City Honors (whose student body was 66% white, 19% black, 7% Latino, and 31% low income) and Olmsted (whose student body was 32% white, 50% black, 10% Latino, and 51% low income). What distinguishes these two schools from other criteria schools with smaller disparities is the heavy use of tests and other academic admissions criteria.

Identifying the barriers

Buffalo Public Schools hired The Civil Rights Project to identify barriers to equitable access in the district’s criteria schools and propose solutions, which, if accepted by both parties, could resolve the civil rights violations and create more equitable access to those schools.

After analyzing enrollment and achievement data, our team took three steps. First, to get the feedback we needed, we recruited a wide array of participants to ensure representation of a range of perspectives, particularly those from marginalized communities. We contacted school district leaders, community members, and religious leaders, distributed fliers at schools, and made an announcement at a districtwide parent meeting about the research we were conducting. We also generated phone and email messages that were distributed by the district office.

Second, we collected data from 1,721 people — which included district officials, principals, teachers, counselors, parents, and students — through individual site-based interviews, phone interviews, focus groups, online surveys, and phone surveys conducted in both Spanish and English.

Third, we analyzed the data by coding participants’ responses. Responses were categorized into the topics of recruitment, outreach, communication, information, transportation, preparation in earlier grades, admissions criteria, enrollment, registration policies, and support for English language learners and students with disabilities. This analysis directly informed our recommendations for policy changes.

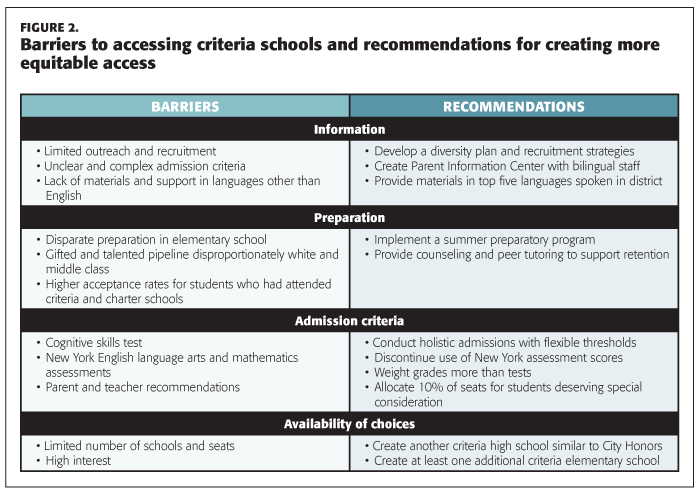

We identified barriers in four areas that students of color, low-income students, and English language learners faced in accessing the criteria schools (see Fig. 2).

Barrier #1: Information

Providing clear and accessible information to all families is important for creating an equitable school choice system. Families cannot access a choice if they don’t know about it. However, in Buffalo Public Schools, information was hard to find. And when it was available, it was unclear, complex, and provided only in English.

The district’s outreach efforts were limited. Most parents and students gathered information about criteria schools through social interactions, sometimes with school personnel but usually with other parents or students. Parents and students noted that the district’s web site was outdated and difficult to navigate; perhaps as a result, fewer than 5% of parents relied on the web site for information. When parents were asked about the information they received from the district, one of five reported never having received any information about school choices.

For students and parents who were aware of the criteria schools, the admission criteria and the admission process were complicated and unclear. As a veteran 30-year teacher described, “Knowledge of these schools’ existence — what it takes to be accepted, entrance in schools before high school, process to apply — as a BPS teacher, I didn’t know all of this. Not only are criteria schools a mystery to students and parents, [but also] . . . the programs available are extremely confusing, constantly changing, difficult to navigate and it’s extremely difficult to obtain information.” Confirming this sentiment, 46% of the parents whose children applied to criteria schools reported that the process was “very difficult or confusing” and 29% reported it as “somewhat difficult or confusing.”

Finally, families and students whose native language is not English had a particularly difficult time obtaining information about criteria schools because, as one teacher explained, “the phone calls and information provided are all in English.”

Barrier #2: Preparation

Students must have the academic preparation to be competitive as applicants to criteria schools; however, some students didn’t have access to equitable educational opportunities in earlier grades. In Buffalo Public Schools, as across the United States, schools with high concentrations of students of color and low-income students had lower levels of academic achievement. In Buffalo’s highly segregated schools, this meant students of color and low-income students often attended schools with inexperienced teachers, less challenging curricula, and less competitive classrooms.

Further, there appeared to be an unofficial pipeline between some elementary schools and the criteria high schools. For example, there was one criteria elementary school with a gifted program, which enrolled a disproportionately large share of white (47%) and middle-class (62%) students compared with the district percentages (21% white, 19% middle class). Not surprisingly, a large share of students from this elementary school was admitted to the most desirable criteria high schools. Similarly, students who had attended charter schools were more likely to be admitted to criteria high schools than students who had attended Buffalo Public Schools primary schools. Among all students who applied to criteria schools, 47% were accepted; however, 94% of applicants who had earlier attended a criteria school were accepted, as were 70% of applicants who had attended a charter school.

Barrier #3: Admission criteria

Acceptance to City Honors and Olmsted was based on several criteria, including a cognitive skills test, the New York state English language arts and mathematics assessments, grades, and teacher and parent recommendations. Evidence indicates that these criteria create additional barriers.

Cognitive skills tests are intended to measure a student’s reasoning and problem-solving abilities, but they often reflect students’ knowledge, not their abilities. Knowledge is influenced by environmental factors, and students have unequal access to the knowledge that is assessed on standard IQ tests (Fagan & Holland, 2007).

The use of students’ scores on the New York state English language arts and mathematics assessments raises concern for all students because the assessments were newly adopted and aligned to the Common Core State Standards in 2013. Thus, their reliability and validity are currently uncertain, a concern that the New York Common Core Task Force (2015) expressed in its report cautioning against using the test scores to evaluate students or teachers until 2019.

Requiring recommendations can create an additional barrier for students of color and low-income students. Many Buffalo parents, as well as district staff, said parent recommendations could be ambiguous and culturally biased, a belief that is confirmed in research, which finds that parent recommendations are often complex, cumbersome, culturally insensitive, and lacking reliability and validity (Ford, 1998). Teacher recommendations also can create barriers for students of color. Recent research (Grissom & Redding, 2016) found that black students are referred to gifted programs at significantly lower rates when they’re taught by nonblack teachers. When Buffalo Public Schools’ court order ended, so did the directives about faculty diversity, resulting in a teaching staff that was more than 85% white in 2014.

Barrier #4: Availability of choices

Participants consistently shared the viewpoint that the number of seats available for students in high-quality criteria schools was insufficient. As a parent said, “There aren’t enough desirable schools in the area.” A counselor reiterated the point: “You can be qualified for a criteria school and not be accepted because there’s not enough space.”

Our recommendations

To address the barriers, we crafted recommendations based in the research literature about how to make choice systems fair (see Fig. 2). In some instances, we borrowed from higher education literature. Our recommendations are aligned with the joint guidance from the U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Education (2011) regarding how schools can create diverse student bodies and also are consistent with ideas shared by Buffalo educators, parents, and students. We believe these recommendations could serve as a general blueprint for other districts, local conditions permitting.

Addressing information. First, we urged the district to develop a diversity plan that would include flexible goals for increasing diversity by race, poverty, and language at each school. These goals are targets for recruitment and enrollment efforts, not quotas that would set aside seats for students of a particular race. The district should collect data and monitor progress on these goals. We also recommended that the district create a Parent Information Center to serve as a central hub of information about available choices and how the choice system works. Printed materials should be available in the top five languages spoken in the district, which change from year to year and recently have included English, Spanish, Arabic, Burmese, Karen, Nepali, and Somali. At least one staff member should be bilingual in the district’s top language. In addition, we suggested that the district proactively reach out to students by having teachers and students from criteria schools visit other schools in the system to share information about their school’s offerings and application procedures.

Excellence should be replicated, not rationed.

Addressing preparation. To provide students with additional preparation, we proposed that Buffalo Public Schools create a summer preparatory program that provides students from less competitive elementary schools an opportunity to prepare before the admissions period. We also encouraged the district to create counseling and peer tutoring programs that would operate during the school year to support the retention of traditionally underrepresented students after they have enrolled in criteria schools.

Addressing admission criteria. We proposed that the district eliminate the use of the Common Core-aligned tests as admission criteria. Student grades should receive greater weight than test scores because grades are a better predictor of academic success (Geiser & Santelices, 2007). We recommended that admission criteria be considered holistically rather than in isolation, with flexible thresholds, rather than absolute cut points for each criterion, thus basing the admission decision on each applicant as a whole. Further, we proposed setting aside 10% of seats in each criteria school for students who deserve special consideration on the basis of such factors as obstacles overcome, exceptional dedication, unusual success in a school isolated by race and poverty, or coming from a section of the city that is rarely represented in criteria schools.

Addressing availability of choices. Finally, we recommended increasing the number of schools and seats in high-quality diverse schools. Acknowledging the work that would be required to do so, one principal stated, “I think that would take major resources and . . . major planning . . . but I have some ideas for how that could happen. It would take people to be patient and dedicated to it, but I think we could do it.” Accordingly, we proposed that Buffalo Public Schools develop two additional criteria schools — one elementary school and one high school. Excellence should be replicated, not rationed.

The broader implications

The Buffalo study shows that when the civil rights rules of court-ordered magnet school plans are replaced by a system in which allocation of scarce spots in excellent schools is turned over to local school authorities with no oversight, resegregation and severe inequity can reoccur. The civil rights complaint in Buffalo stemmed from a claim that the criteria for selecting students were discriminatory — not that those criteria had been selected intentionally to discriminate but that they did, in fact, produce that result. During our time in the district, Buffalo’s principals, teachers, students, parents, and community advocates all described a highly unequal system of school choice plagued by multiple barriers to information and admission.

On the basis of our findings, we called for changes in the criteria. We were convinced, however, that eliminating all criteria would harm the reputation of excellent schools. Instead, we proposed lowering the importance of test scores; ending the use of the new and unproven New York state tests; ending absolute cut points for scores; increasing consideration of other measures; and setting aside a fraction of admissions to be made outside this process, among other recommendations.

In reaching the settlement with the Office for Civil Rights, the school system accepted many of our proposed changes in its outreach and recruitment process but refused to end the excessive reliance on test scores or expand the supply of high-achieving schools. Although some positive changes occurred, the outcomes did not change at City Honors. The tests must be changed, and there must be explicit goals for increasing minority representation.

Equity doesn’t occur unless it’s an explicit goal and policies are adopted to attain it.

Amid growing nationwide concern about inequitable access to exam schools, alongside the spread of school choice more generally, our recommendations for Buffalo have broader application. Here are some lessons we can draw from this work:

- There’s a strong relationship among the lifting of civil rights goals, changing the mechanisms in choice plans, and increased stratification in school districts. Equity doesn’t occur unless it’s an explicit goal, and policies are adopted to attain it.

- In the absence of a cooperative and capable school district, greater equity calls for simpler, fewer unambiguous requirements even though they may produce fewer gains in equitable access and diversity than a more complex multidimensional remedy would produce.

- In a segregated and unequal city, high reliance on testing without affirmative action policies is likely to reinforce and legitimate inequality.

- There are many feasible, educationally advantageous, and potentially popular remedies that are noncoercive and could improve conditions. However, in settings committed to the status quo or too divided to act, a stronger combination of external incentives and sanctions may be necessary to overcome roadblocks and trigger deeper and more effective reforms.

Civil rights enforcement can play a vital role in this process. The research community has much to offer in terms of clearly documenting and raising awareness about existing trends. We encourage advocates and researchers to document the effects of current choice systems, and we encourage educators to work with them to increase fairness in their schools.

References

Fagan, J.F. & Holland, C.R. (2007). Racial equality in intelligence: Predictions from a theory of intelligence as processing. Intelligence, 35 (4), 319-344.

Ford, D.Y. (1998). The underrepresentation of minority students in gifted education: Problems and promises in recruitment and retention. Journal of Special Education, 32 (1), 4-14.

Geiser, S. & Santelices, M.V. (2007). Validity of high-school grades in predicting student success beyond the freshman year: High-school record vs. standardized tests as indicators of four-year college outcomes. Berkeley, CA: Center for Studies in Higher Education.

Grissom, J.A. & Redding, C. (2016). Discretion and disproportionality: Explaining the underrepresentation of high-achieving students of color in gifted programs. AERA Open, 2 (1), 1-25.

New York Common Core Task Force. (2015). New York Common Core Task Force final report. New York, NY: Author.

Newsweek. (2013). America’s best high schools. Newsweek. www.newsweek.com/2013/05/06/america-s-best-high-schools.html

Orfield, G., Ayscue, J., Ee, J., Frankenberg, E., Siegel-Hawley, G., Woodward, N., & Amlani, N. (2015). Better choices for Buffalo’s students: Expanding & reforming the criteria schools system. Los Angeles, CA: The Civil Rights Project.

U.S. Department of Justice & U.S. Department of Education. (2011). Guidance on the voluntary use of race to achieve diversity and avoid racial isolation in elementary and secondary schools. Washington, DC: Author. www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/guidance-ese-201111.pdf

Citation: Ayscue, J.B., Siegel-Hawley, G., Woodward, B. & Orfield, G. (2016). When choice fosters inequality, can research help? Phi Delta Kappan, 98 (4), 49-54.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Brian Woodward

BRIAN WOODWARD is a doctoral candidate in the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, University of California, Los Angeles.

Gary Orfield

GARY ORFIELD is distinguished research professor of education, law, political science, and urban planning and codirector of The Civil Rights Project, University of California, Los Angeles.

Genevieve Siegel-Hawley

Genevieve Siegel-Hawley is a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. She is the author of A Single Garment: Creating Intentionally Diverse Schools That Benefit All Children (Harvard Education Press, 2020).

Jennifer B. Ayscue

JENNIFER B. AYSCUE is research director of the Initiative for School Integration at The Civil Rights Project, University of California, Los Angeles.