While state governments have had a heavy hand in teacher preparation, licensure, and certification policy for over a century (American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education, 1990; Hawley, 1990), states have traditionally delegated teacher tenure and evaluation policy to localities, often in conjunction with local collective bargaining units (Ballou, 2000; Cohen-Vogel & Osborne-Lampkin, 2007; Hannaway & Rotherham, 2006; Hungerford & Blom, 2014; Strunk, 2012). Over the past decade, however, the actors involved in teacher evaluation and tenure issues have changed.

Most prominently, the federal government launched a series of programs — the Race to the Top (RTT) competition in 2009 and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) Flexibility Program in 2011 — that emphasized states’ development of systems tying teacher performance evaluations and tenure decisions to student achievement. The federal government’s most recent action — the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) — continues to emphasize state teacher evaluation and tenure systems; however, it explicitly forbids the U.S. Secretary of Education to force states to set up specific teacher evaluation policies.

Nonetheless, before ESSA, many states invested in the revision and development of policies tying teacher evaluation and tenure to student achievement. In fact, 42 states and the District of Columbia now have teacher evaluation policies written into state law or regulations, meaning that these policies would need to endure substantial political scrutiny in order to be revised once again. Given these circumstances, some scholars have voiced skepticism in ESSA’s ability to shift states’ approaches to teacher evaluation and tenure (Sawchuk, 2016; Wong, 2015). However, teachers union leaders have voiced optimism, seeing “an opening to change policies their members have broadly rejected” (Sawchuk, 2016).

But if states do choose to make changes, how much influence will teachers have on these decisions? Scholars have established that teachers and their unions have substantial influence at the local level (Hess, 2002; Lieberman, 1997; Moe, 2002, 2011). However, save for anecdotal evidence, we know very little about whether and how state education policy makers take their voices into account — or any other voices, for that matter — when making policy decisions related to teacher evaluation and tenure.

Surveying state education policy makers

As part of a larger project that aimed to understand whose voices are heard in the state education policy-making process, I surveyed state education policy makers in the spring and fall of 2016 to determine whose voices they valued when making teacher evaluation policy. The survey targeted state-level government actors who have the formal authority to review, accept, amend, and reject binding education statutes and administrative rules — namely, state legislators serving on an education committee and state board of education (SBE) members.

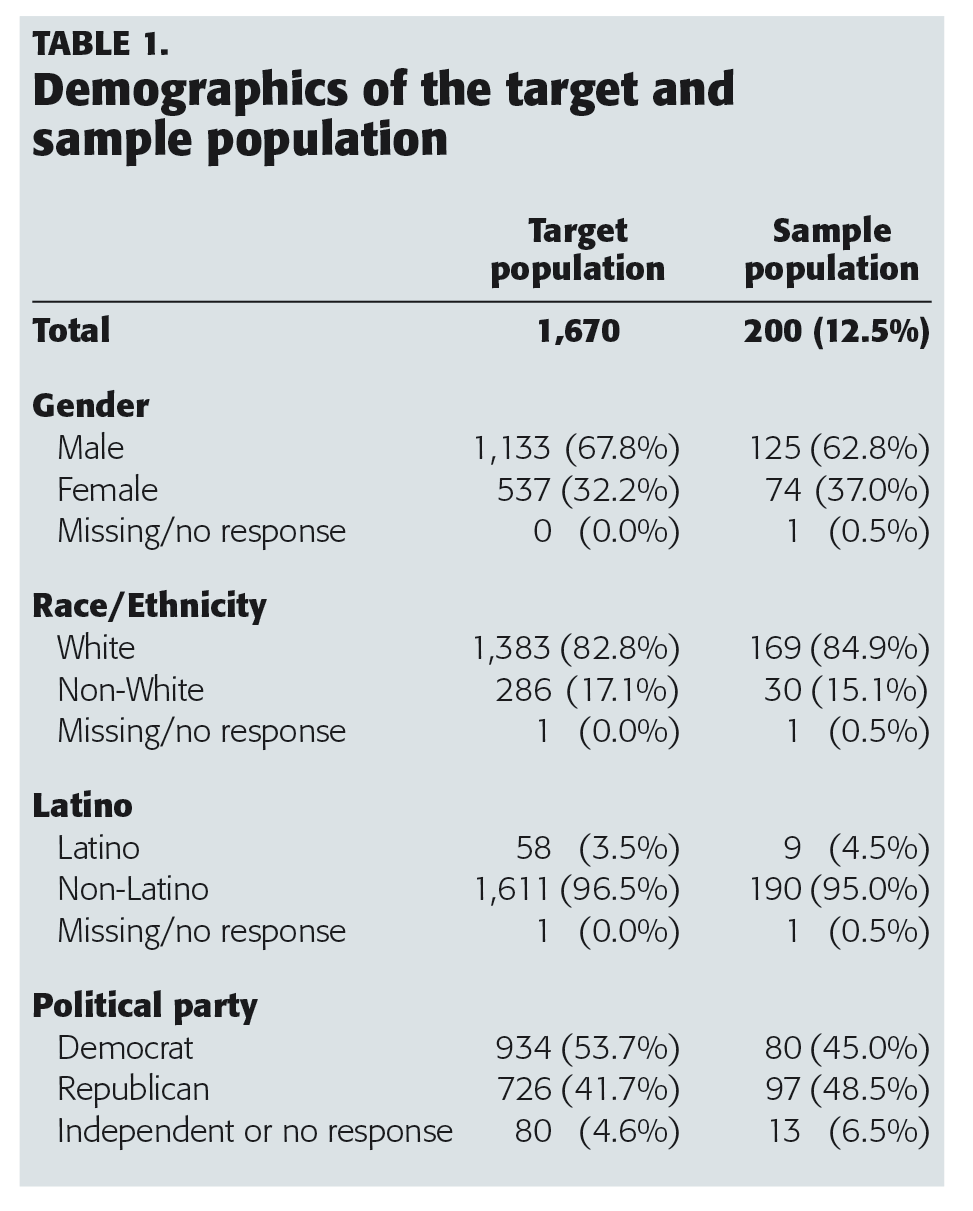

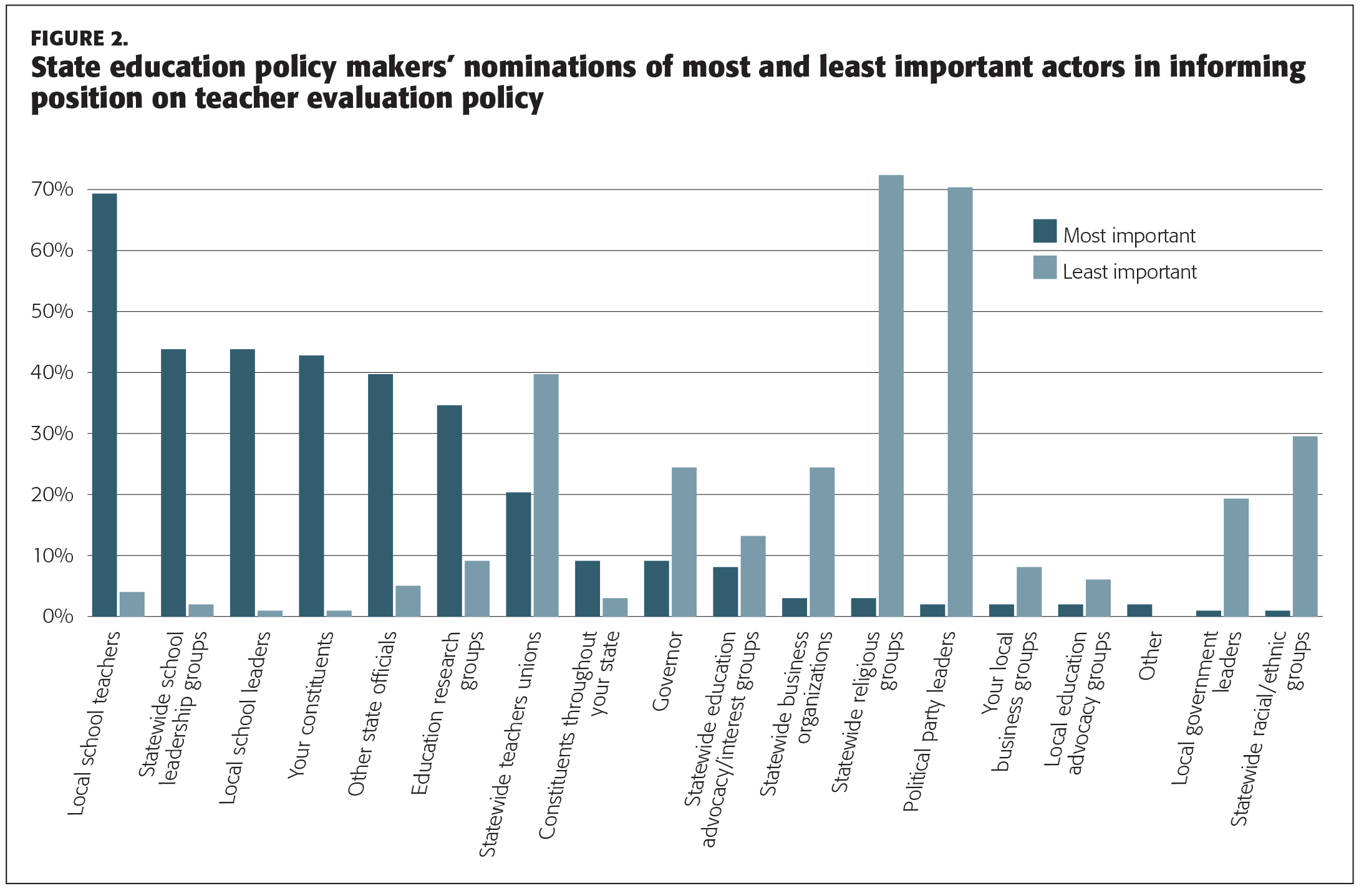

Two hundred individuals responded to the online survey, resulting in a response rate of 13 percent. While this response rate is far from spectacular, it serves as a starting point for filling a large gap in the state education policy-making literature. The demographics of my survey respondents were relatively representative of all state education policy makers when it came to race/ethnicity, but women and Republicans were slightly more prevalent in my sample than in the target population (see Table 1).

My survey included one experimental question and three universal questions, with each providing a nuanced understanding of whose voices state education policy makers value when making teacher evaluation policy decisions. The first survey question was a randomized control trial in which I randomly assigned state education policy makers to one of three conditions:

- Members of the control group were asked whether they would be inclined to vote in support of or in opposition to a teacher evaluation policy change that would remove the use of data from students’ performance on state assessments in teachers’ performance evaluation. No other information was provided to those in the control group.

- Those assigned to treatment condition A were given the same question followed by a statement about the general public’s level of support for the policy change in question.

- Those assigned to treatment condition B were given the same question followed by a statement about teachers’ support for the policy change.

In both treatment conditions, the statements about public and teacher support were drawn from the 2013 Education Next/Harvard University Poll on School Reform.

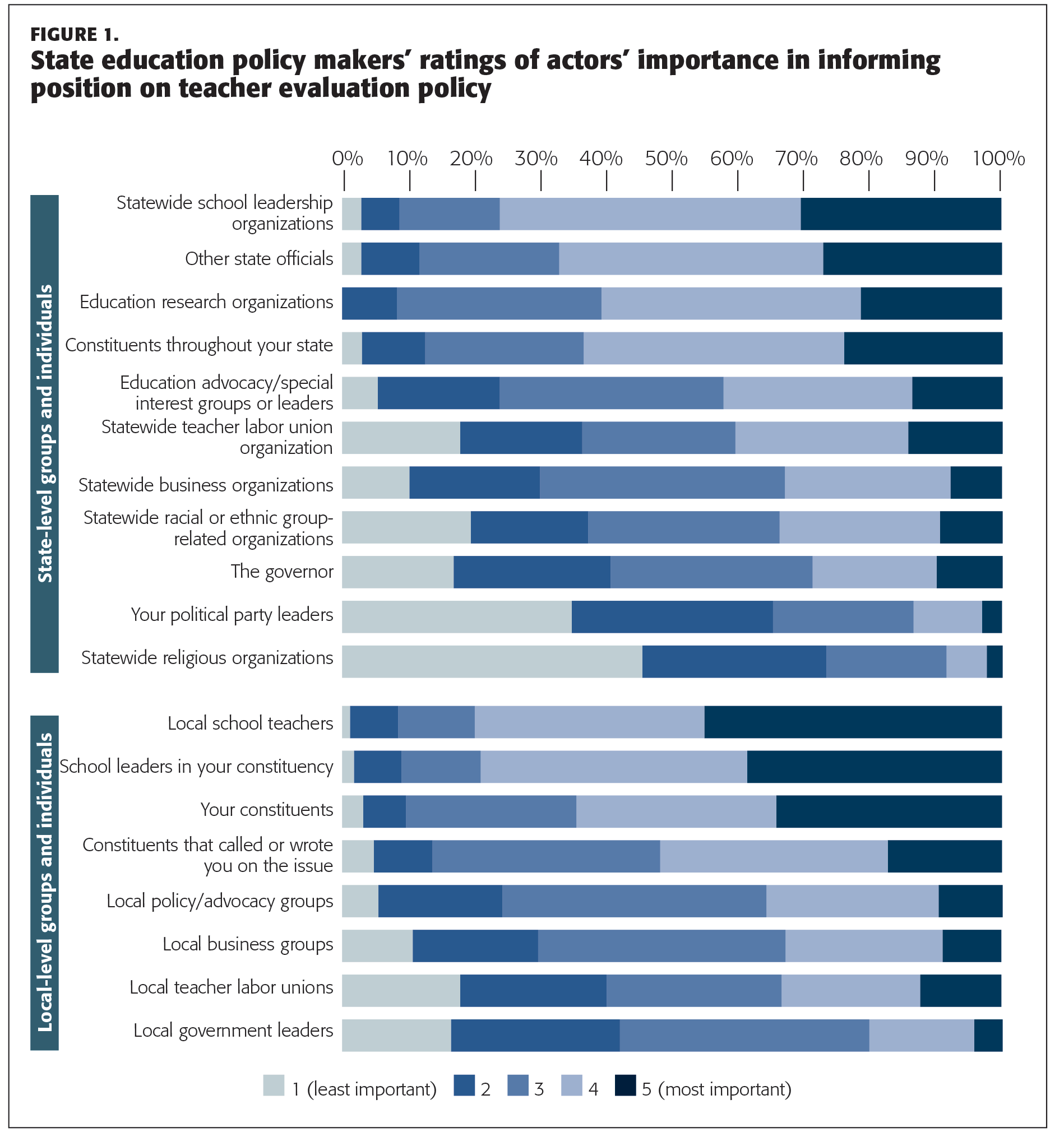

Understanding that state education policy makers may be unresponsive to the teacher evaluation policy preferences of both the general public and teachers, I also included two uniform survey questions to understand the value state education policy makers placed on various voices. One survey item asked respondents to rate, on a scale of 1 (not important) to 5 (very important), the importance of various actors in informing their position on teacher evaluation policy. A second item asked them to select the two most important and two least important actors in informing their position.

To analyze the experimental question data, I modeled state education policy makers’ policy preferences (0=support; 1=oppose) as a function of the control/treatment group to which they were randomly assigned. I then ran additional regression models to explore whether and how their race, gender, political party affiliation, education level, institutional home (i.e., SBE or legislature), and geographic location related to their position on the teacher evaluation policy change.

Finding #1: Policy makers are unresponsive to policy preferences of the general public, but they value the voices of constituents.

State education policy makers who were randomly exposed to data that revealed the teacher evaluation policy preference of the general public were not significantly more likely to align with the general public’s teacher evaluation policy position. However, when asked to rate the importance of constituent voices in informing their position, both “constituents throughout your state” and “your constituents” consistently received ratings of “important” and “very important” (see Figure 1). Similarly, “your constituents” was among the most frequently selected “most important” voices that state education policy makers consider when taking a position on teacher evaluation policy (see Figure 2).

This pattern of state education policy makers placing lower value on the voices of a group of people and higher value on individuals they have some connection to was prevalent across a number of findings.

Finding #2: Democrats and Republicans differ in their responsiveness to teacher preferences.

Overall, respondents’ positions on teacher evaluation policy appeared to be unaffected by their exposure to the policy preferences of teachers. However, I found a statistically significant relationship between a policy maker’s political party and their position on the teacher evaluation policy change.

My initial suspicion was that this relationship would be driven by Democrats, who were more likely to take a policy position that aligned with the policy preference of teachers regardless of their control/treatment group. But when I dug a bit deeper (by running separate models, one with data solely from Republicans and another with data solely from Democrats), I found it was Republicans whose responses more heavily weighted these results: If a Republican was exposed to the data on teachers’ policy preferences, their likelihood of voting in the opposite direction of teachers increased by 95 percent.

I also found Democrats exposed to the data on teachers’ policy preferences were not more likely to vote in line with teachers’ preferences. For Democrats, the small magnitude of the effect is likely an artifact of Democrats’ predisposed alignment with teacher policy preferences, regardless of whether they are exposed to teacher policy preferences. This finding is consistent with Leslie Finger’s (2017) finding that where Democrats have more control in the legislature, increases in teachers union strength have an effect that is smaller in magnitude on the likelihood of passing certain education reforms than in Republican-dominated legislatures. Together, these findings lend support to the theory that Democrats automatically align with the interests of teachers unions.

Finding #3: How teacher voices are presented may affect the extent to which those voices are valued.

When asked to rate the importance of various actors’ voices in informing their position on teacher evaluation policy, nearly all state education policy makers — Democrats and Republicans alike — consistently rated “local school teachers” as “very important” (see Figure 1). Similarly, when asked to select the most and least important actors in informing their position on an education policy, nearly all state education policy makers selected “local school teachers” as one of the most important actors (see Figure 2).

In contrast, statewide and local teachers unions received high ratings from Democrats (average of 3.7 for state and 3.6 for local), but low ratings from Republicans (average of 2.4 for state and 2.7 for local). Similarly, Democrats frequently selected statewide teachers unions as one of the most important groups informing their position on teacher evaluation policy. In contrast, Republicans frequently selected state teachers unions as one of the least important groups.

While these findings provided some support for what has been termed “the war on teachers” (Giroux, 2013; Goldstein, 2015), in which the “intelligence, judgment, and experience that teachers might offer in [current education] debates” are ignored (Giroux, 2013, p. 3), a more holistic look at my findings provides some support for Eric Hanushek’s (2011) proposition that there “is not a war on teachers en masse.” Rather, policy makers — particularly Republicans — seem to be nonresponsive (and, in some cases, intentionally unresponsive) to the policy preferences of teachers when presented as an organized group, though they place relatively high value on the voices of individual teachers.

We know very little about whether and how state education policy makers take teacher voices into account — or any other voices, for that matter — when making policy decisions related to teacher evaluation and tenure.

The small sample of survey respondents and the focus on a single policy case study of teacher evaluation policy does not allow for my results to be generalized to all state education policy makers and issues. Yet, these results suggest it may be important to understand who these individual teachers and groups of teachers are.

Finding #4: Nearly all state education policy makers value individual and organized voices of school leaders.

While state education policy makers differed by party in their responsiveness to teacher voices, they did not discriminate between the value of individual and organized voices of school leaders. As revealed in the rating and most/least likely question data (see Figures 1 and 2), the voices of individual school leaders and school leadership groups were highly valued by all state education policy makers. Again, however, it is important to understand the makeup of the individual and organized voices of school leaders.

The results of this study suggest that school leaders can have a profound effect on teacher evaluation policy. Yet school leaders “tend to think of the entire [education governance] system as a hierarchical-linear system, meaning that they feel they cannot influence parts of the system much ‘higher’ or ‘lower’ than their level” (Jean-Marie, Normore, & Brooks, 2009, p. 17). Further, a recent survey conducted by the Education Week Research Center (2017) found that 65 percent of school and district leaders have avoided political activities out of concern that they might create problems with their jobs. The findings from this study emphasize the importance of providing school leaders with the knowledge, skill, and will to engage with state education policy makers.

States taking charge

With the passage of ESSA and initial efforts under the Trump administration to shift education policy making back to the states, state education policy makers will have an opportunity to reshape teacher evaluation, if they so choose. Those who care about their state’s teacher evaluation policy need to understand whose voices policy makers value.

Although this survey focused on the teacher evaluation policy-making process, I hope others will build on this work by exploring whose voices are heard when other important education policy issues are debated, and whose voices other government actors (e.g., chief state school officers, governors, judges) are likely to value. In addition, a larger-scale study with a higher response rate could be generalized to all state education policy makers. Perhaps national organizations (such as the National Association of State Boards of Education, National Conference of State Legislatures, Council of Chief State School Officers, and National Governors Association) could help expand this research to inform our understanding of the state education policy-making process.

References

American Association of Colleges of Teachers Education [AACTE]. (1990). Teacher education policy in the states: A 50-state survey of legislative and administrative actions. Washington, DC: Author.

Ballou, D. (2000). Teacher contracts in Massachusetts. Boston, MA: Pioneer Institute for Public Policy Research.

Cohen-Vogel, L. & Osborne-Lampkin, L. (2007). Allocating quality: Collective bargaining agreements and administrative discretion over teacher assignment. Educational Administration Quarterly, 43 (4), 433-461.

Education Next. (2013). Education Next — Program on Education Policy and Governance — Survey 2013. Cambridge, MA: Author. http://educationnext.org/files/2013ednextpoll.pdf

Education Week Research Center. (2017, December). Educator political perceptions: A national survey. Bethesda, MD: Author.

Finger, L.K. (2017). Vested interests and the diffusion of education policy reform across the states. Policy Studies Journal.

Giroux, H. (2013). Neoliberalism’s war against teachers in dark times. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies, 13 (6), 458-468.

Goldstein, D. (2015). The teacher wars: A history of America’s most embattled profession. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Hannaway, J. & Rotherham, A.J. (Eds.). (2006). Collective bargaining in education: Negotiating change in today’s schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Hanushek, E. (2011). The “war on teachers” is a myth. Hoover Digest, 1.

Hawley, W.D. (1990). Systematic analysis, public policy making, and teacher education. In W. Houston (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 136-156). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Hess, F.M. (2002). School boards at the dawn of the 21st century: Conditions and challenges of district governance. Alexandria, VA: National School Boards Association.

Hungerford, N.J. & Blom, M.C. (2014). Collective bargaining and the negotiation process: A primer for school board negotiators. Washington, DC: National School Boards Association & Council of School Attorneys.

Jean-Marie, G., Normore, A.H., & Brooks, J.S. (2009). Leadership for social justice: Preparing 21st century school leaders for a new social order. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 4 (1), 1-31.

Lieberman, M. (1997). The teachers unions. New York, NY: Free Press.

Moe, T.M. (2002). Political control and the power of the agent. Paper presented at the Conference for Controlling the Bureaucracy, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX.

Moe, T.M. (2011). Special interest: Teachers unions and America’s public schools. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Sawchuk, S. (2016). Law could spur change in teacher requirements. Education Week, 35 (15), 14-15.

Strunk, K.O. (2012). Policy poison or promise? Exploring the dual nature of California school district collective bargaining agreements. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48 (3), 506-547.

Wong, A. (2015, December 9). The bloated rhetoric of No Child Left Behind’s demise. The Atlantic.

Citation: White, R.S. (2018). The case of teacher evaluation: Who do state policy makers listen to? Phi Delta Kappan 99 (8), 13-18.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rachel S. White

Rachel S. White is an assistant professor of K-12 educational leadership at Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA.