In the Harbor Freight Fellows Initiative, high-potential students who struggle in traditional CTE programs demonstrate their ability to learn outside school.

Actor Peter Falk, made famous by his role as Columbo in the eponymous 1970s television series, once shared a story about his glass eye. When he was three years old, he explained, he had retinoblastoma and had to have his right eye removed. Years later, when he sought to qualify for the Merchant Marines, he was required to pass a vision test. The examiner told him to cover his right eye, and Falk read the chart perfectly. Then the examiner told him to cover his left eye. Said Falk, “I can’t see. I got a glass eye.” The examiner responded, “Well, do the best you can.”

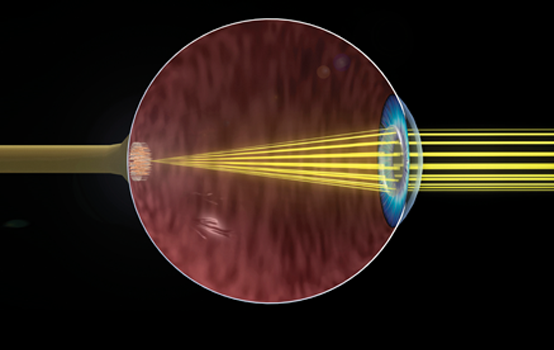

While Falk had lost his right eye to cancer, the examiner’s blindness was self-inflicted. Charged with a task, he took no account of the person in front of him. His sole concern was to administer the exam. The story reminds me of the horse-driven carriages lined up outside New York City’s Central Park. The horses wear blinders that prevent them from seeing behind and to the side, enabling their handlers to better control their movements. Similarly, it calls to mind current approaches to assessment in K-12 education. By using a small set of indicators and measures (e.g., scores on reading and math tests, attendance records, grades, completion of course sequences, and graduation rates) to define and judge student success, educators are donning blinders of their own.

Today, school leaders tend to be fixated on using big data to crunch a narrow set of numbers, rather than actually thinking big — and deep and broad — about learning. And the more sophisticated the technology they apply (or misapply) to the same handful of indicators, the less clearly they see their students. They use test results to assign learners to groups so that schools can provide “appropriate” interventions, but they don’t actually know very much about the varying talents and interests of the individuals they put into those groups, nor do they know much about the personal struggles they may be facing that can profoundly affect their performance.

Further, they may not be able to imagine other ways of assessing students, or — consistent with Abraham Maslow’s observation that a fear of knowing is a fear of doing — they may lack the courage to look more deeply at the talent that sits before them. After all, if they did so, then they might feel obliged to act on what they learn, and this could interfere with their ability to complete the tasks they’ve been assigned. Worse yet, if educators allowed themselves to know more about their students, then they might be forced to acknowledge that the whole system needs to be redesigned.

But why, given its rapidly expanding ability to collect and analyze seemingly endless streams of data, does the educational system remain so narrowly fixated on the same few indicators? Why can’t we use the power of big data to collect different and better measures that look more broadly and deeply at the things students can and want to do, not just in the classroom but also outside of school?

Seeing things differently

For decades, educators have been concerned mainly with certifying that students have obtained certain academic, career, and social-emotional competencies at school. But this ignores the vast amounts of learning that young people do outside of school, often from people who observe them closely in real-world contexts and can speak volumes about their skills and knowledge. This sort of “privileged information” (Raad, 2008) — gained through field experience and offered by knowledgeable adults — remains invisible to our assessment systems, no matter how big the data. Because the blinders are on, though, we think we see the whole picture.

Traditional indicators and measures are at best incomplete; often, they are perniciously inaccurate, even as they delude us into believing we actually know the individual learner. A student might ace an interim standardized test, indicating they are on track to succeed, while also facing significant issues at home that could increase their likelihood of dropping out of school before graduation. Or a student might be engaged in pursuing a passion that presents valuable learning opportunities but does not necessarily improve their grades and test scores. We can’t understand students unless we expand our vision.

- Related: Ready for what? Confusion around college and career readiness

- Related: Creating pathways and opportunities for youth

Over the past year, a team at Big Picture Learning (BPL) has been attempting to get that broader view by developing a new approach to career and technical education (CTE) and workplace learning that includes an assessment strategy that taps the insights of mentors, peers, and others who know students both inside and outside the school setting.

This “apprenticing” program is called the Harbor Freight Fellows Initiative (HFFI) and is supported by Harbor Freight Tools for Schools. Our target population is young men and women who have demonstrated outsized competence in a trade, but who may be struggling to negotiate the rigid structures of time and space and other aspects of a traditional high school or CTE program.

A growing body of research and best practice provides robust evidence that student interest, serious and deep practice, and long-term adult relationships lead to high levels of learning (Bloom, 1985; Blustein, 2011; Coyle, 2009; Deci et al.,1991; Kenny, 2013; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Washor & Mojkowski, 2011, 2013). We see these features and components in those CTE programs that have a deep and sustained place-based workplace component where students work with mentors in the trades. Big data appears to have missed this kind of learning completely. But if we widen our view, it’s possible to see how much some students would benefit from an intensive field experience with a mentor who can not only help them bring their tradecraft to a much higher level but also introduce them to a community of practice in which they can continue developing their skills.

In HFFI, we pay close attention to every student’s background, interests, and academic, cultural, social-emotional, and health needs, and we assess their progress both inside and outside of the school. This requires us to get to know them and their personal stories as well as to know their families, friends, and communities. It also requires us to learn about the kinds of social capital — e.g., the norms, customs, values, and lingo — that they will need to acquire as they pursue their tradecraft. This begins with the program application (see “Getting to know you”), which the school’s fellowship adviser uses to guide students’ placements, and it continues with ongoing assessments by students’ mentors over the course of the year.

Data from the applications and early assessments indicate that HFFI students have all sorts of passions, talents, skills, and knowledge long before they come to us. They may work for their families in a small business, they may enjoy tinkering in a garage with friends or family, or they may belong to a club dedicated to a specific interest. Responding to an inner drive, they may spend enormous amounts of time on these pursuits, often collaborating with peers and adults with similar interests, creating informal (and sometimes formal) communities of practice in which their work is validated by adults, expert mentors, and peers. In some cases, their understanding is already deep and broad enough to be worthy of a badge or certification.

Asking different questions

Our work suggests how critical it is to ask questions about students’ background knowledge and experiences, their interests and passions, their likes and dislikes, their academic and career goals, their access to mentors and other supportive adults, their participation in formal and informal communities of practice, their knowledge about local and national workforce needs, the understanding of licensure and certification requirements, and on and on.

Conversations between students, mentors, and teachers may reveal competencies and potential futures that test scores do not.

For the mentors, the priority is to build a trusting relationship with students and to collect information about the wide range of competencies they develop in school and the workplace. But this raises some tricky questions about the measurement of knowledge and skills. For example, what combination of work products, classroom performances, and academic assessments can give a complete and valid picture of what students know and can do? And how can we make sense of the ways in which their performance might vary from one context to the other — such as when a student does poorly on a classroom math test but shows a solid command of roughly the same mathematics when asked to solve applied problems in the workplace?

We’ve discovered that conversations between students, mentors, and teachers may reveal competencies and potential futures that test scores do not. For instance, when a student told his mentor and CTE teacher that he “dreams about HVAC,” his passion and enthusiasm were evident, and his CTE teacher noted how different he is when is doing something important to him — and how being able to participate in that field experience affected his engagement in his classes back at school. The general manager of the company where the student was placed said he can see this student with the company for years to come, again verifying the student had potential that traditional measures did not reveal.

When we take our blinders off and start these conversations, we get a much deeper and broader perspective on students and the ways in which they want to navigate through the educational system. And of course, the answers they give may require us to make changes to the culture, systems, structures, practices, and policies we’re used to in K-12 education.

To date, the assessment data from Harbor Freight Fellows program suggest that:

- Our students are most interested in educational experiences that put them into professional settings. Doing work that has real value to businesses and customers is both more engaging than work done at school and accelerates the acquisition of both trade skills and workplace skills such as collaboration, organization, and communication.

- Exposure to, and immersion in, professional communities of practice in students’ trade interest builds relationships that lead to career and further educational opportunities not available in school-based CTE programs.

- Work in professional settings is instrumental in the growth of self-confidence and feelings of self-respect, accurate self-assessment of ability, and the ability to make well-informed plans for the future.

- Our students describe the relationships they develop with their mentors and advisers as key to their progress in academics and workplace skills, as well as their growth as citizens and community members.

- Our students have often struggled with academic classroom settings and been judged as unmotivated, undisciplined, and unintellectual. However, when placed in work settings, these same students tend to be attentive, responsible, respectful, and curious.

These findings have greatly helped us to refine and improve our program. However, none of them was produced by traditional forms of school assessment. We’ve learned these things because we’ve asked the right sorts of questions of our students, their peers, their teachers, and others, and because we’ve made it a priority to assign mentors to collect such information, observe students in school and at work sites, and keep an eye on their progress over time.

To date, HFFI has focused on highly talented and high-potential youth with an interest in trades who may be struggling within the traditional CTE design program. But might the same kinds of opportunities apply to all students in all CTE schools? Would it be possible (and cost-effective) to give every CTE student a similar learning experience?

Peter Falk’s accomplishments as an Emmy and Golden Globe winner inspire us to find within each young person the interests and the talents that can serve as the springboard for deep and sustained learning. Infusing apprenticing, mentoring, and communities of practice into all CTE programs will require us to expand our understanding of what young people can do and to adopt a very different but immensely valuable vision of success.

References

Bloom, B.S. (1985). Developing talent in young people. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Blustein, D.L. (2011, August). A relational theory of working. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79 (1), 1–17.

Coyle, D. (2009). Talent code: Greatness isn’t born, it’s grown. Here’s how. New York, NY: Bantam.

Deci, E.L., Vallerand, R.J., Pelletier, L.G., & Ryan, R.M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. The Educational Psychologist, 26, 325-346.

Kenny, M.E. (2013). The promise of work as a component of educational reform. In D.L. Blustein (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the psychology of working. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Raad, R. (2008). Evaluating sources of clinical knowledge. American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, 10 (3), 154-157.

Washor, E. & Mojkowski, C. (2011, April 5). The knowledge funnel: A new model for learning. Edutopia.

Washor, E. & Mojkowski, C. (2013). Leaving to learn: How out-of-school learning increases student engagement and reduces dropout rates. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Citation: Washor, E. (2018). A wider vision of learning and assessment. Phi Delta Kappan 99 (7), 67-71.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Elliot Washor

ELLIOT WASHOR is cofounder of Big Picture Learning in Providence, R.I.