So-called promise scholarships shape dreams for students and encourage changes in educator beliefs about students.

So-called promise scholarships shape dreams for students and encourage changes in educator beliefs about students.

This past summer, LeBron James was in the news for something that had nothing to do with basketball or his moves from Cleveland to Miami and back to Cleveland. In August 2015, the LeBron James Family Foundation and the University of Akron announced a partnership that could put as many as 2,300 Akron kids through college. As part of the foundation’s I Promise program, scholarships covering tuition and general fees will be made available to students involved in programs sponsored by the James Family Foundation; the first potential recipients will graduate high school in 2021.

Promise scholarship programs such as the one developed by the basketball superstar or even the Scott’s Tots program devised by the fictitious Michael Scott of television’s “The Office” are a distinct type of college scholarship. Promise programs are place-based scholarships, generally tied to a city or school district, offering near-universal access to all living in the place. While promise programs share some characteristics with other scholarship programs, they’re unique because they seek to change communities and schools.

The promise movement is in its infancy, born in November 2005, when Kalamazoo Public Schools superintendent Janice Brown announced that a group of anonymous philanthropists had essentially guaranteed college scholarships to all high school graduates in Kalamazoo going forward. Scholarships covered full tuition and fees at any of Michigan’s 44 public community colleges and four-year universities. Scholarships are awarded to all Kalamazoo graduates, regardless of merit or need, with few strings attached. This unprecedented strategy was intended to revitalize the region and encourage families to remain in the Kalamazoo school system. The Kalamazoo Promise drew widespread media attention and caught the eye of many interested in community revitalization across the country, including civic leaders in the small, southern Arkansas town of El Dorado. Within two years, in January 2007, a similar promise program was born in El Dorado.

Underlying such promise programs is the belief that having access to a guaranteed college scholarship will encourage students to remain in school, encourage families to remain in a community, and change how educators work with students. Based on our analysis of student performance data in El Dorado since 2007, we learned that this promise program did improve student achievement throughout the system as early as elementary and middle school (Ash, 2015). Interviews with El Dorado teachers and school leaders also revealed that a genuine culture shift occurred in El Dorado after the Promise began.

According to Sylvia Thompson, director of the El Dorado Promise since the program’s inception, more than 1,800 graduates of El Dorado High School have received the Promise Scholarship through fall 2015. Thus, starting in the fall semester of 2007, about 200 students in each El Dorado High School graduating class have benefited directly from the program. As of this writing, we are gathering and organizing college enrollment data from the National Student Clearinghouse to rigorously assess the extent to which the Promise program has improved college participation and completion rates for El Dorado students.

The Promise comes to El Dorado

The Promise comes to El Dorado

In spring 2006, after reading about the Kalamazoo Promise, community business leaders in El Dorado met with Murphy Oil Corp. executives to propose starting a promise-like program in El Dorado. Murphy Oil, a Fortune 500 company, is headquartered in El Dorado and has a history of funding special programs in the school district. These civic leaders were persuasive, and, in December 2006, Murphy Oil’s board of directors approved a $50 million gift to create the El Dorado Promise, a universal college scholarship program for El Dorado School District graduates.

Unlike traditional forms of financial aid, which typically have merit and/or financial need requirements, the El Dorado Promise scholarship is available to all students, provided they have been continuously enrolled in the district since at least 9th grade and graduate from El Dorado High School.

Similar to other promise programs, the El Dorado Promise was established not only to increase the number of college graduates from the area and improve the local education system but also to spur economic development. Like many communities in southern Arkansas, El Dorado, a city of about 20,000 people located a short distance north of the Louisiana border, has suffered population loss and the closing or relocation of many of its major employers in recent decades (Landrum, 2008). Murphy Oil representatives have said they hope the Promise will have a number of economic benefits for the company and the community, including increasing Murphy Oil’s ability to recruit talent, attract business investment, and create better employment opportunities for returning college graduates (Landrum, 2008).

The El Dorado Promise scholarship can be applied toward tuition and mandatory fees for up to five years at any accredited two- or four-year college or university in the country, private or public. The maximum amount payable is the highest annual resident tuition and mandatory fees at an Arkansas public university, which was $7,889 for a student taking 30 credit hours per year in the 2014-15 school year. The El Dorado Promise can be used in combination with other forms of financial aid, including need-based aid such as the Pell Grant ($5,730/year maximum value for 2014-15) and merit-based scholarships such as the Arkansas Academic Challenge Scholarship or “lottery scholarship” ($2,000 to $5,000/year for 2014-15). The El Dorado Promise is considered a “first-dollar” scholarship; it can be used for any college expenses that appear on a student’s college invoice, such as room, board, and textbooks. Depending on the institution a student attends and other forms of aid, combining the Promise with other forms of financial aid could pay the full cost of college attendance.

The amount of the scholarship depends on a student’s length of enrollment in the school district. Students who have been continuously enrolled in El Dorado since kindergarten are eligible for 100% of the scholarship value; the amount decreases to 95% for students who initially enrolled in 1st through 3rd grades and then decreases by an additional 5% for initially enrolling in each subsequent grade level until 9th grade, when students are eligible for 65% of the scholarship value. Students who enroll in the district in 10th grade or later are not eligible for the Promise.

The amount of the scholarship depends on a student’s length of enrollment in the school district. Students who have been continuously enrolled in El Dorado since kindergarten are eligible for 100% of the scholarship value; the amount decreases to 95% for students who initially enrolled in 1st through 3rd grades and then decreases by an additional 5% for initially enrolling in each subsequent grade level until 9th grade, when students are eligible for 65% of the scholarship value. Students who enroll in the district in 10th grade or later are not eligible for the Promise.

The Promise must be used to seek an associate or bachelor’s degree; it cannot be used for technical certificates. To use the Promise, students must enroll in an accredited higher education institution in the semester immediately following high school graduation, unless they defer enrollment to join the military.

To keep the Promise scholarship, students must be enrolled in at least 12 credit hours per semester, maintain a 2.0 cumulative grade point average, earn at least 24 credits per academic year, and be making progress toward a bachelor’s or associate degree.

What is the theory of change?

While promise programs are primarily intended to improve students’ higher education outcomes, they’re also expected to improve K-12 outcomes. The El Dorado Promise might be expected to produce better K-12 outcomes by motivating or influencing its key stakeholders in several ways:

- Students may become more motivated to prepare for college; they may enroll in more rigorous coursework or simply become more invested in school and exert more effort.

- Similarly, parents may be encouraged by the accessibility of college and choose to play an active role in ensuring that their children are prepared to take advantage of the postsecondary opportunities the Promise presents.

- School leaders in the El Dorado school district may start new programs to increase students’ college-readiness.

- Teachers may work harder to reach students because the lost opportunity associated with academic failure will greatly increase.

Of course, the Promise is most likely to work through a combination of several possible changes.

Over the past couple of years, we have gathered a great deal of data to assess the extent to which the district has changed and how El Dorado students have benefited from the Promise, even before they cashed a single tuition check in college. We studied enrollment trends in El Dorado compared to similar districts before and after the Promise began and found a range of positive effects (Ash & Ritter, 2014). We also engaged in hours of discussions with nearly 20 teachers and school leaders and concluded that a culture change had taken place since the Promise began.

Enrollment increased. In the pre-Promise period (1990-91 to 2005-06), El Dorado lost about 10% of its population. From 2007-08 to 2011-12, El Dorado district enrollment experienced a 9% increase above its expected trend, while comparison district enrollment continued on the same downward trend and the surrounding Union County district enrollment dropped more than expected. The fact that enrollment in other county districts and similar comparison districts continued to fall while El Dorado School District enrollment increased indicates that the introduction of the El Dorado Promise positively affected district enrollment.

Student learning improved. Using the annual Arkansas Benchmark exams, we evaluated whether the achievement gains of El Dorado students were greater than would have been expected. We first matched each El Dorado student in grades 3 through 8 with a matched “twin” student in the same grade in another Arkansas district. Students in the same grade and with the same race, gender, and free-lunch eligibility status were matched by student test scores on the Arkansas Benchmark exam as of spring 2006. The result of this matching was a comparison group of students that, in fall 2006, was nearly identical to the group of El Dorado students in fall 2006. The next step was simply to analyze student scores from 2007 forward and determine whether the achievement of the El Dorado group outpaced that of the initially matched comparison group.

The results of this analysis are presented in great detail in Ash (2015). Overall, we found that El Dorado Promise students’ test scores were roughly 6% to 8% of a standard deviation better than their matched peers each year in mathematics achievement. Moreover, these gains compounded over time for up to three years. Thus, for many of the students in the sample who were in elementary grades in 2007 and spent three or more years in El Dorado after the Promise was announced, the cumulative effect of the Promise was substantial. When we analyzed subgroups, we found that the effects of the Promise were greatest for the most academically able students, that is, students who scored in the top half of their class before the Promise was announced. Importantly, these gains did not come at the expense of traditionally underserved students, including economically disadvantaged students or African-American students. In fact, the program effects for students in these subgroups were as large as the overall program effects.

This finding makes sense: The promise of a college scholarship appeared to have the greatest effect on academically strong students (those who would be most likely to seek higher education), as well as positive, but not statistically significant, effects on students from traditionally underserved groups (who might not have considered higher education to be economically feasible).

In our view, this is great news. Of course, there is still much left to be learned about the effect of the El Dorado Promise program or promise programs in general. In the case of El Dorado, we will soon know more about the extent to which this program changed the pattern of college attendance and college success among Promise recipients. So far, we have evidence that the program resulted in test score gains for El Dorado students before 8th grade. The analyses described thus far, however, do not give us any insight as to how these positive changes occurred. Why would the promise of a college scholarship after grade 12, for example, influence student test scores in grades 6, 7, or 8?

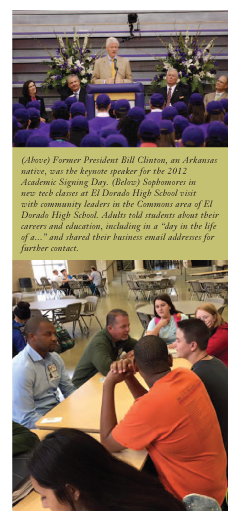

Discussions of college permeate the district from kindergarten onward. Since the introduction of the Promise, school officials have engaged in a number of practices to expose students to college at a young age. That starts with a local bank giving kindergartners El Dorado Promise backpacks filled with information about college and the Promise scholarship. Since 2007, conversations about college and trips to college campuses have become commonplace for all students in the district, regardless of race or class. Since the Promise began, middle school students can take an elective course called College 101. As the name suggests, the course gives students introductory information on what college life is like and what it takes to get to college. The director of the El Dorado Promise coteaches a career course to 7th graders, in which she talks to students about college and how the Promise supports college attendance. The director revisits students in high school English classes to encourage college applications and requires each student to visit her in the Promise office. Finally, in April of senior year, El Dorado holds a very public Academic Signing Day, which all seniors attend in graduation robes and announce the college they will attend. The importance of this event is signified by the very prominent guests who have attended and spoken over the years: At the 2012 Academic Signing Day, former President Bill Clinton was the keynote speaker.

It seems obvious that everyone in town knows about the Promise and knows many people who attend college; El Dorado certainly has a college-going culture. According to El Dorado educators, these changes have had a genuine effect on students and their own educational aspirations. “It’s been a total shift in mindset. Every kindergartner will tell you they’re going to college. It’s not pie in the sky anymore. It’s reality,” one teacher said.

Another educator said, “Even at the lower levels, we no longer say if you go to college. We say when you go to college.”

Enhanced expectations for all students. Interviews with teachers and school leaders revealed that El Dorado educators redoubled their efforts to ensure that they held high expectations for all students since all El Dorado students now had the financial means to attend college. According to most of the interviewees, from the superintendent to the elementary teachers, we got the impression that district leaders were always willing, even before the Promise, to try new strategies to reach students. Nevertheless, the consensus from our participants was that teachers began to hold higher expectations and push students even harder after January 2007.

One teacher, who teaches pre-AP courses in middle school, described a compromise that she is no longer willing to make: “I am less likely to let that kid sit in the back and live in la-la land. Ten years ago, I might’ve done that. ‘OK, you don’t want to learn this; if I just let you zone out, you’re not going to bother anyone else, OK, I’m gonna deal with everybody else.’ [Since the Promise, I now say] ‘No, it’s not OK for you to do that. It’s not OK for you to sit here and not attempt to do this work, because you’ve got somewhere to go from here.’”

Another teacher said this new mindset even affects how he deals with discipline. “I found, post-Promise, that I’m now less likely to let the discipline problems keep me from teaching. I’m a lot more inclined to get in touch with parents to address the issues.”

Another teacher said this new mindset even affects how he deals with discipline. “I found, post-Promise, that I’m now less likely to let the discipline problems keep me from teaching. I’m a lot more inclined to get in touch with parents to address the issues.”

Indeed, the compromises described here sound quite similar to the one made by Horace Smith in the classic education book Horace’s Compromise by education reformer Ted Sizer. Since the Promise was announced, teachers across the district are less willing to make that compromise. Our interviewees said the administration began doing classroom walk-throughs to ensure that teachers are keeping all students engaged. Again, the teachers described to us an apparent culture shift. “The culture has changed. Those teachers [not attempting to reach all students] are being replaced. The culture here is we expect every student to be participating in class. The teacher’s job is to reach every kid. If a kid’s not engaged, our job is to make an attempt.”

One teacher put it more succinctly: “When we first got the Promise, our job changed because all these kids have a chance to go to college.”

Increased enrollment in advanced coursework for all students. One very tangible result of increased expectations by both students and teachers was the spike in enrollment in Advanced Placement (AP) and pre-AP courses across El Dorado. Since the Promise, teachers and administrators have felt a weighty responsibility to ensure that all students are prepared for college. One strategy for increasing college readiness is enrolling students in AP coursework. Nearly all interviewees — from the director of professional development to the teachers to the counselors — said AP classes are enrolling more students and a greater diversity of students.

Before the Promise, El Dorado had an AP program; in fact, the district had AP programs since the onset of such programs. However, many years ago, very few students were enrolled in AP courses, and those who were enrolled were nearly always affluent, white students. According to the district’s director of professional development, before the Promise, fewer than 100 AP exams were taken each year. In 2013, El Dorado students took more than 600 AP exams, and she estimates that economically disadvantaged students took one-third of those exams. We heard stories of tables filled by black females at Saturday afternoon preparation sessions for AP calculus. The El Dorado AP teachers we met seemed especially proud that their classes were now reaching students across the socioeconomic spectrum. In referencing the changes since 2007, one AP teacher joked that “our AP program has gone from the country club to parks and rec.”

AP courses had always been open to any students who applied, “but it wasn’t advertised as open enrollment, and it wasn’t encouraged,” one teacher said. Since the Promise, El Dorado educators have made an intentional effort to encourage all types of students to enroll in AP courses and college prep courses. AP teachers encourage teachers in regular courses to move students into AP if they show potential. Teachers in feeder courses are now inclined to seek students who are successful and encourage them: “You need to think about being an AP kid.”

These efforts aimed at expanding and diversifying the AP track are clearly in line with the post-Promise high expectations encouraged throughout the district. On the heels of the Promise, the educators in El Dorado were driven to step it up, in their words, because “we are trying to literally get all of the kids ready for college.”

Michelle Miller-Adams has studied the Kalamazoo Promise since its beginnings in 2005 and is one of the nation’s leading researchers on promise programs. In her 2009 book, The Power of a Promise, Miller-Adams writes that the Kalamazoo Promise “has been variously described as a scholarship program, an economic development strategy, a boon to the middle class and a gift to the poor” (p. 2). Promoters of promise programs are enthusiastic about the potential for such programs to improve the overall well-being of communities through various channels. Most directly, the promise should lead to greater participation in postsecondary schooling by reducing costs and red tape that accompanies most forms of financial aid. Along the way, supporters hope that promise programs can support K-12 schools and community development by retaining current residents and attracting new ones.

And finally, perhaps it is possible that the promise of a clear financial path to college, even for students in elementary and middle school, can improve academic opportunities and enhance expectations throughout a local school system. The experience of students and educators in El Dorado, Ark., suggests that such a promise indeed can nurture positive changes throughout a district.

References

Ash, J.W. (2015). A Promise kept in El Dorado? An evaluation of the impact of a universal, place-based college scholarship on K-12 achievement and high school graduation (Doctoral dissertation). Fayetteville AR: University of Arkansas (Order No. 3700408).

Ash, J.W. & Ritter, G.W. (2014). Early impacts of the El Dorado Promise on enrollment and achievement. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas. http://bit.ly/1MZzqPJ

Landrum, N.E. (2008). Murphy Oil and the El Dorado Promise: A case of strategic philanthropy. Journal of Business Inquiry, 7 (1), 79-85.

Miller-Adams, M. (2009). The power of a promise: Education and economic renewal in Kalamazoo. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Citation: Ritter, G.W. & Ash, J. (2016). The promise of a college scholarship transforms a district. Phi Delta Kappan, 97 (5), 13-19. © 2016 Phi Delta Kappa International. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Gary W. Ritter

GARY W. RITTER is a professor of education and public policy and holder of the endowed chair in education policy in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Ark.

Jennifer Ash

JENNIFER ASH is a senior analyst at Abt Associates, Cambridge, Mass.