The authors suggest a three-part conceptual framework to help community school coordinators plan and assess the wide range of services they provide to children and families.

Community schools are designed to integrate a variety of academic programs, social services, and economic supports for students, families, and community members by strategically bringing resources from partner organizations into schools. This holistic approach moves beyond a narrow focus on individual children and considers the larger forces that influence students’ well-being.

While community schools operate in a wide range of urban and rural areas, they play particularly important roles in neighborhoods affected by poverty, systematic disinvestment, and segregation (Shaia, 2016; Shaia & Crowder, 2017). One of the key figures in every community school is the site coordinator, a dedicated member of the school’s leadership team who identifies stud ents and families’ most pressing needs and directs resources to help meet them. Today, though, when all kinds of schools are subject to constant measurement and tough demands for accountability, community school coordinators are confronting difficult questions about their work. Critics ask, for example, precisely what outcomes do they hope to achieve? And why favor the community schools model rather than other approaches for delivering services to those who need them?

ents and families’ most pressing needs and directs resources to help meet them. Today, though, when all kinds of schools are subject to constant measurement and tough demands for accountability, community school coordinators are confronting difficult questions about their work. Critics ask, for example, precisely what outcomes do they hope to achieve? And why favor the community schools model rather than other approaches for delivering services to those who need them?

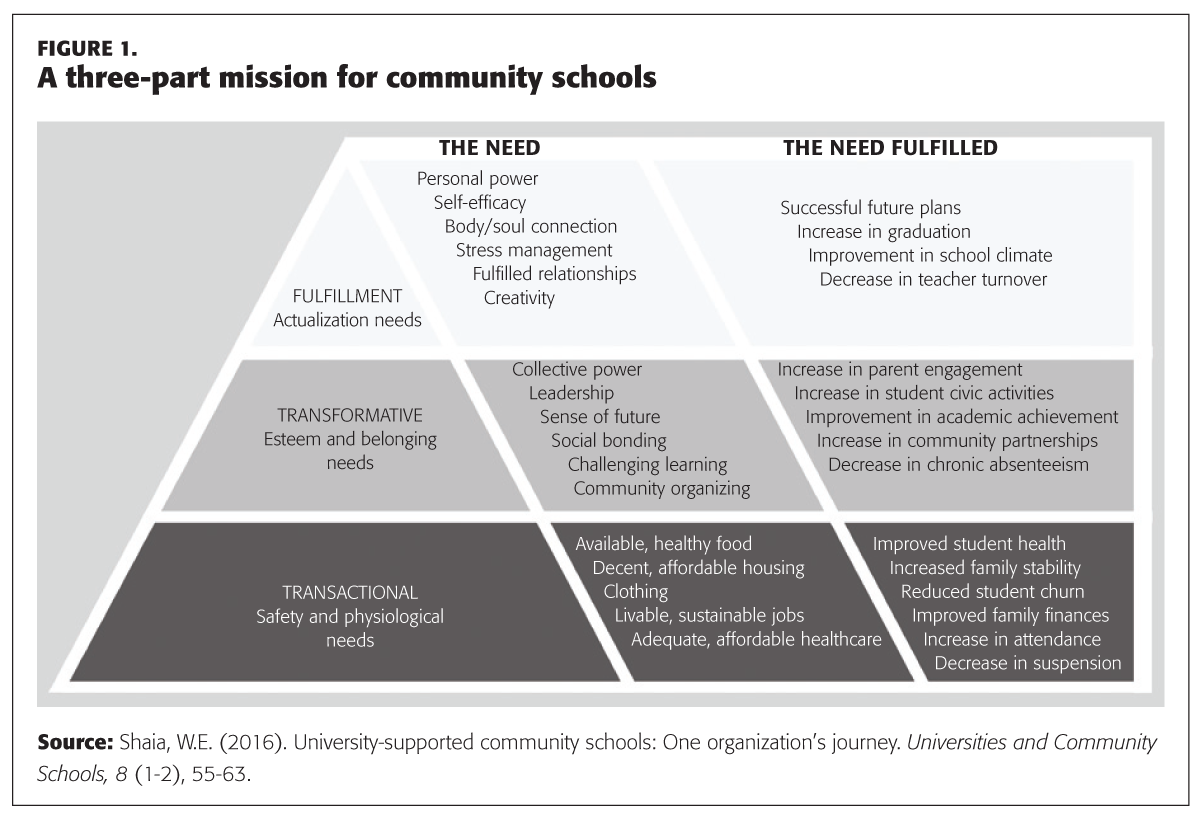

In this article, we offer a planning framework meant to help flesh out the mission, goals, and desired outcomes of local community schools, as well as to highlight the distinct value of the larger community schools model. Specifically, we describe what are typically called the transactional and transformative approaches to coordinating and delivering services, and we suggest a third approach, which we call fulfillment, that points toward more ambitious outcomes for children and other community members.

Three dimensions of planning

A transactional approach to planning and programming focuses on the long-term quality and sustainability of essential services that must be provided continuously. For example, this includes efforts to keep food pantries stocked and accessible, provide winter coats and other clothing when necessary, arrange health and dental care for those who are suffering, offer financial coaching to families during tax season, and meet emergency housing needs for those who’ve had to leave their homes. Such transactional services are absolutely critical, as they are meant to ensure day-to-day survival and stability for children and their families.

Transformational services aim to help children and families develop and strengthen their own power to determine the course of their lives. At this level, the focus is not just to meet immediate needs but also to build a sense of agency and self-esteem by tapping opportunities for collective action. For example, students and their caregivers might be asked to help identify specific ways to improve their schools and communities, such as by creating academically challenging after-school programs or confronting bias in school disciplinary practices. Often, a transformative approach is meant to address the deeper root causes of everyday problems facing families, such as inequitable housing policies, unjust patterns of criminal sentencing, and a lack of access to child care, transportation, and other services.

Neither of these efforts — finding ways to meet transactional needs and providing transformational opportunities to build social bonds and address the causes of everyday problems — is straightforward. Gains and successes often unravel due to the traumatic experiences of students, families, teachers, school staff, administrators, and others living and working in segregated and impoverished communities (Shaia, 2016).

For this reason, we recommend also that community schools design and deliver programs meant to promote what we call fulfillment: the capacity to withstand and counteract the continuing effects of poverty by building healthy relationships, finding avenues for creative expression, managing stress, and planning for the future. For example, this might include school and community services that focus on restorative justice, mindfulness, social-emotional learning, character development, and the building of leadership skills.

To help community schools decide how to prioritize, assess, and evaluate the services they provide, we have found it useful to organize these approaches into a framework loosely modeled after Abraham Maslow’s (1943) well-known Hierarchy of Needs (see Figure 1). Most fundamental is the work of addressing transactional needs by bringing in partner organizations to stock the food pantry, distribute clothing, offer medical, dental, and mental health treatment, and provide other essential services and supports. Only if basic needs are met can site coordinators make successful efforts to engage children and parents in school and community activities, help them organize to influence school practices, and help school leadership and staff become more responsive.

Further, community schools can best engage children and families in pursuing more fulfilling lives if they have also made progress at the transformational level.

Our proposed framework is neither linear nor chronological — community schools should focus on whichever level makes sense for them and their clients at the time. The important thing is that they take an intentional and strategic approach to deciding which levels to address, when, how, and with what resources. When considering any new program or when taking a second look at an existing program, they should ask themselves: Precisely what outcome is this activity designed to achieve? Is it focused on meeting transactional needs, addressing the root causes of local problems, or laying the foundation for students and families to thrive over the long term?

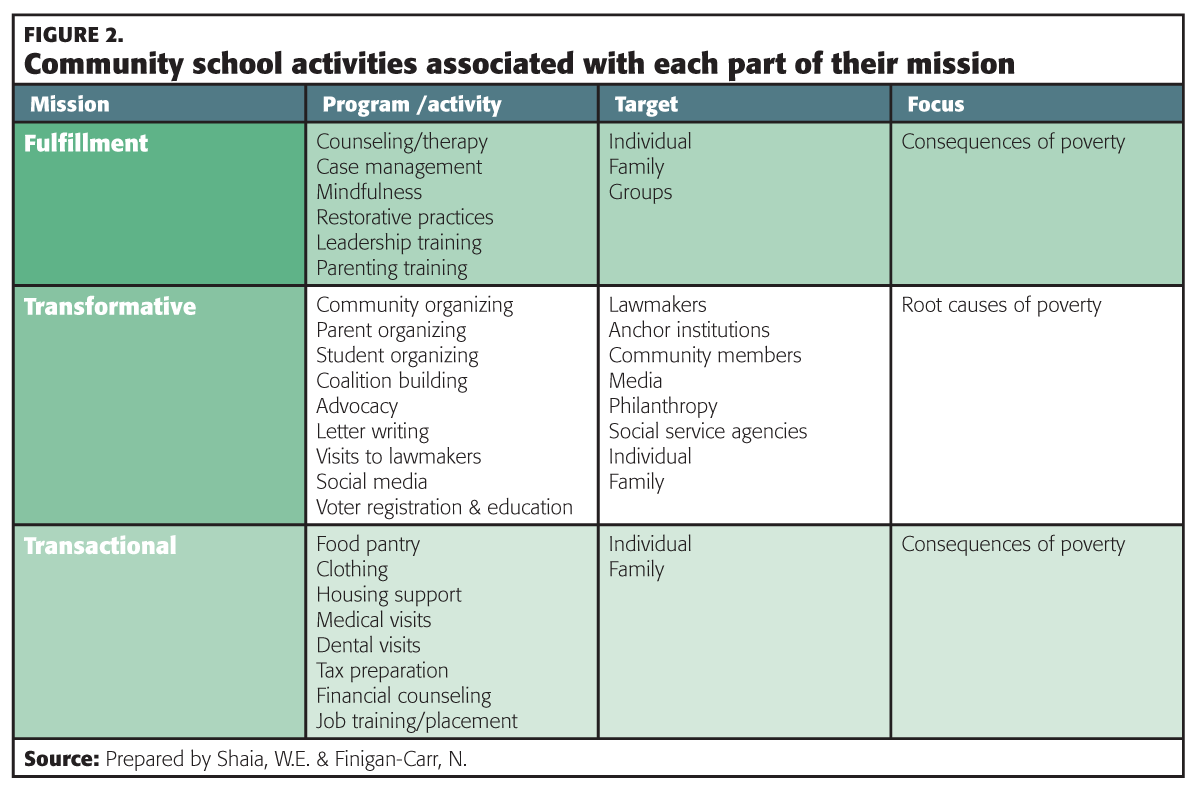

Many community schools provide effective programs and services at the transactional level (e.g., running food pantries and health clinics). Further, in recent years, as educators and social workers have become more informed about the causes and effects of childhood and family trauma, many schools have begun to address the level of fulfillment (e.g., by teaching mindfulness, prioritizing student’s social-emotional learning, and expanding access to college and career planning). However, many schools struggle at the transformational level where the aim is not just to provide basic services and teach new skills but to form partnerships with students and parents that will help them build their own power.

At this level, community school staff must be willing to relinquish some control and play a supportive role for students, parents, and community members as they become leaders, strengthen their voices, and perhaps even disagree with and demand changes in the school and other service providers. Teachers, staff, and site coordinators may find it difficult to take a back seat in this way. But local community members must be motivated and empowered to stand up, criticize the status quo, define the changes they want, and act (Lee, 2001), whether that means leading voter registration drives, advocating for new legislation, or organizing parents to change school policies. (See Figure 2 for examples of the kinds of activities associated with each level.)

While community school site coordinators may lead the effort to plan and manage local programs, this type of transformational work cannot depend solely on them. Rather, it requires an organization-wide commitment to sharing certain kinds of leadership with members of the community. School administrators, in particular, must agree to keep the lines of communication open to students and parents who choose to express their needs and desires, exercise their rights, and call for specific changes. That may strike some people as a recipe for disaster, bringing endless conflict into the school, but administrators must keep in mind that the most vocal students and parents tend to be the most engaged and dedicated to long-term improvement.

Assessing outcomes at each level

Of these three levels of programming, transactional services tend to be the simplest to assess, as they can often be counted or measured quantitatively. For example, a community can assess a food bank’s effect by counting the number and percentage of families who receive food, measuring the amount of food distributed, or calculating the number of people who could potentially be provided with the minimum recommended number of servings per day for each food group (Cotugna, Vickery, & Glick, 1994).

The other two levels of the framework (transformative and fulfillment) are not as easily quantified. Rather, the challenge is to assess the quality of processes, outputs, and outcomes and then use that information to demonstrate each program’s effect and inform efforts to improve it. Further, at these two levels, assessment tends to occur over an extended time since the goal is to measure long-term changes in stakeholders’ behaviors, sense of agency, and engagement as well as to determine the extent to which specific programs and services contributed to those changes. At a minimum, then, the evaluation of programs focusing on transformation and fulfillment should include:

- A mix of formative and summative methods of assessment, with stakeholders invited to help choose and develop those methods;

- Well-defined metrics to measure changes in community engagement; and

- A commitment to sharing data, highlighting promising practices, and using findings to help guide school operations and strategic planning.

Given the emphasis on helping children and families take active roles in improving their own schools and communities, it is hard to overstate how critical it is to gather input from key stakeholders throughout the assessment process. Further, every assessment plan should begin with a community mapping activity that identifies the specific groups represented in the area and asks members of each group to define their most pressing needs and goals, their priorities for school improvement, and the extent to which the community school’s services are (or could be) aligned with those priorities.

At the same time, as children and families become more engaged and empowered to pursue their own goals, it becomes difficult to distinguish between the accomplishments of the community school and the things community members have accomplished through their own actions. In short, cooperative partnerships — featuring joint planning and shared responsibility among stakeholder groups — are tricky to assess. Measuring the long-term changes in community members’ behaviors, beliefs, and engagement is important, as is assessing the quality of the shared decision making, the effectiveness of the partnership, and efforts to pursue changes at the community school or elsewhere in the community.

This goes well beyond the typical effort to measure a program’s outcomes against predetermined metrics. For example, the assessment might include surveys of community members’ well-being and mental health — both individually and throughout the wider community — using tools such as interviews, focus groups, document analysis, and other instruments, such as the Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory (Mattesich, Murray-Close, & Monsey, 2001).

This is complex and time-consuming work, but given the nature of the challenges facing people in areas affected by intense poverty and segregation, there is no choice but to embrace that complexity. Community schools can help students and families meet immediate needs, create a hopeful vision for the future, and achieve long-term, sustainable improvements in their lives. But, to do so, site coordinators must be diligent in planning, delivering, and assessing the wide-ranging services and supports that they provide, touching on all three of the missions described here.

References

Cotugna, N., Vickery, C.E., & Glick, M. (1994). An outcome evaluation of a food bank program. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 94 (8), 888-890.

Lee, J.A.B. (2001). The empowerment approach to social work practice: Building the beloved community (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396.

Mattesich, P., Murray-Close, M., & Monsey, B. (2001). Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory. St Paul, MN: Wilder Research.

Shaia, W.E. (2016). University-supported community schools: One organization’s journey. Universities and Community Schools, 8 (1-2), 55-63.

Shaia, W.E. & Crowder, S.C. (2017). Schools as re-traumatizing environments. In N. Finigan-Carr (Ed.), Linking health and education for African-American students’ success. New York, NY: Routledge Press.

Originally published in February 2018 Phi Delta Kappan 99 (5), 15-18. © 2018 Phi Delta Kappa International. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Nadine Finigan-Carr

NADINE FINIGAN-CARR is a research assistant professor, University of Maryland-Baltimore School of Social Work; she is the author of Linking Health and Education for African-American Students’ Success .

Wendy E. Shaia

WENDY E. SHAIA is a clinical assistant professor and executive director of the Social Work Community Outreach Service, University of Maryland-Baltimore School of Social Work, Baltimore, Md.