Many students with mild disabilities receive no special education services while in high school, leaving them unprepared to succeed in college.

If you imagine something, most likely it is because you can do it. And if you think you don’t want to go to college because you won’t succeed, then I encourage you to think again because whichever university you go to, as long as you communicate properly, they will set you up for success. In other words, don’t let those little things discourage you.

— A university student with a disability offering advice to high school students.

Students who report having disabilities make up roughly 11% of all undergraduates in the United States, and their numbers appear to be growing quickly (Raue & Lewis, 2011; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2009). Most common, within that population, are specific learning disabilities (such as dyslexia and other language disorders) (31%); attention deficit disorder (18%); mental illness, psychological, or psychiatric conditions (15%), and health impairment or conditions (11%) (Raue & Lewis, 2011).

However, in the years before starting college, many of these students never received special education services of any kind. Recently, for example, I surveyed 260 undergraduates who were determined to be eligible for such services once they enrolled at their university (a large public institution in the Pacific Northwest); fewer than 20% said they had received comparable supports in high school.

These students tend to have relatively mild levels of disability, which explains why they slipped through the cracks during high school: While their peers with more serious disabilities were able to secure accommodations, tutoring, counseling, and other services, their own challenges never seemed quite serious enough, in the eyes of teachers and school staff, to warrant diagnostic tests or the creation of an individual education program (IEP). And because their disabilities were mild, they were able to struggle through high school and earn a diploma even without receiving such services.

To say that their disabilities are relatively mild, however, is not to suggest that they don’t need or deserve support. On the contrary, these students face academic, social, and/or psychological challenges that their university deems significant, and which, if not addressed, could make it very difficult for them to succeed in college, which tends to be far more demanding than high school.

This burgeoning population of students with mild disabilities poses an urgent challenge for higher education. In response, many colleges and universities are taking steps to upgrade their student support services, writing centers, tutoring programs, counseling services, and more. But this new sense of responsiveness at the higher education level only underscores how little progress has been made at the high school level.

In publicly funded high schools, students with disabilities are supposed to receive special education services under the guarantee of a free and appropriate education. Specifically, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) allows eligible students to have modifications to the curriculum through an IEP. Alternatively, under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, high school students can gain accommodations that allow them to access the curriculum (but not alter it) in a way that puts them on a level academic playing field with their peers. Similarly, in the college arena, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which governs higher education, provides something akin to a high school 504 plan, which guarantees that students who are otherwise qualified for college will be protected from discrimination based on their disability (29 U.S.C. § 794).

However, the reality is that many qualified high school students do not benefit from either an IEP or 504 plan. This is partly due to underfunding (which has led to cutbacks of counseling staff), partly due to a lack of training for school personnel to identify less immediately discernible disabilities, and partly due to a lack of awareness among students and their families of the complex and changing landscape of disability law. For example, the ADA has long defined a disability as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities” (42 U.S. C. § 12102). But many students and educators are unaware that the ADA definition was broadened in 2009 to include learning, reading, thinking, and concentrating as major life activities, thus entitling even more students to supports. Moreover, with passage of these amendments, the requirements for documenting one’s disability in higher education became less cumbersome (Shaw & Dukes, 2013), paving the way for more students to receive help.

The reality is that many qualified high school students do not benefit from either an IEP or 504 plan.

In high school, the goal of special education is not just to help students reach graduation but also to prepare them for a successful transition to higher education. Without an IEP or 504 plan, they may be able to manage their own disabilities and get through grades 9-12, but they’ll be less likely to gain important skills and information that would help them when they get to college. For example, if they have no prior experience with a supportive special education program, then they may be hesitant to reach out to the campus office of disability support services, out of fear that they’ll be stigmatized. Further, they may be unsure how to access those services, or they may be confused about their rights to do so at the college level. And if they do seek out services, they’ll have to scramble to schedule evaluations, pay for them (unlike in K-12, in higher education the student bears the burden of this cost), and collect the necessary documentation of their disabilities, since they probably won’t have gathered those documents in high school.

Building on the research: College students look back to high school

Contemporary research into the long-term success of students in special education points to the critical importance of helping them navigate the challenges they face. Moreover, rather than focusing on young people’s deficits, or the things they cannot do (a common perspective in past decades), research suggests that it’s more effective to help students build on their strengths and abilities, cultivating a strong sense of self-determination (Kohler & Field, 2003) so they can advocate for whatever services they need to complete their course of studies.

Particularly influential has been a taxonomy, developed by Paula Kohler and her colleagues at the University of Illinois and Western Michigan University, that provides a comprehensive framework for effective transitions beyond secondary school (Test et al., 2009). I used components of Kohler’s taxonomy to shape my own study, which surveyed undergraduates who receive disability services, asking them to think back to their experiences in high school. Unlike previous studies, however, my research focuses specifically on students who did not have an IEP or 504 plan in grades 9-12 — young people who registered for disability services when they got to college but had not previously received such services. In addition, my research aims to expand on the existing knowledge base by identifying supports that can help these students make a successful transition to college and go on to complete their degree programs.

The survey was administered online by the disability service director of a large public university in the Pacific Northwest. Students were asked to reflect on their high school experiences and describe (a) the most important activity, skill, or experience gained in secondary school that would help them graduate from college, (b) what could have been improved about their transition from high school to college, and (c) what advice they might have for high school students with disabilities who want to go to college. (Qualitative data gathered from three open-ended text box survey items were categorized according to a process suggested by Tesch, 1990.)

Of the 1,275 surveys that were sent, 260 were completed and returned (representing a 20% response rate, which is appropriate for such research). The majority of respondents reported having psychological/emotional challenges (39.6%), learning disabilities (27.3%), or chronic/acute health issues (13.8%). These are the disability types that the United States Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (1995) defines as hidden disabilities or mental and physical impairments that are not readily apparent to others and are frequently not properly diagnosed in school. Not surprisingly, only 12.3% of respondents reported that they had a 504 plan in high school, and 6.5% had an IEP.

When asked about the skills they had acquired in high school that were most important to their success in college, most respondents named competencies related to organization, goal setting, and study strategies.

The majority of respondents (82%) enrolled in college directly from high school (or didn’t say), and almost 90% reported that they were likely or very likely to graduate from college. Most were between the ages of 17 and 22, and more than half identified as upper-division students. Respondents were predominately White (72%) and female (65%), did not receive free and reduced lunches in school (81.5%), and were not the first generation in their families to attend college (77%). Roughly 61% indicated that they had visited a college campus while still in high school, and almost 70% said that their family members or guardians (rather than a counselor, teacher, IEP team, or an agency or organization outside school) played a lead role in helping them figure out how to afford college. Survey data did not reveal when students became aware of their disability.

In response to questions about the advice they would give to students who have disabilities but have not received supports in high school, respondents offered ideas that clustered around three main recommendations: Gain an early awareness of resources, develop a strong sense of self-determination, and acquire specific skills.

Early awareness

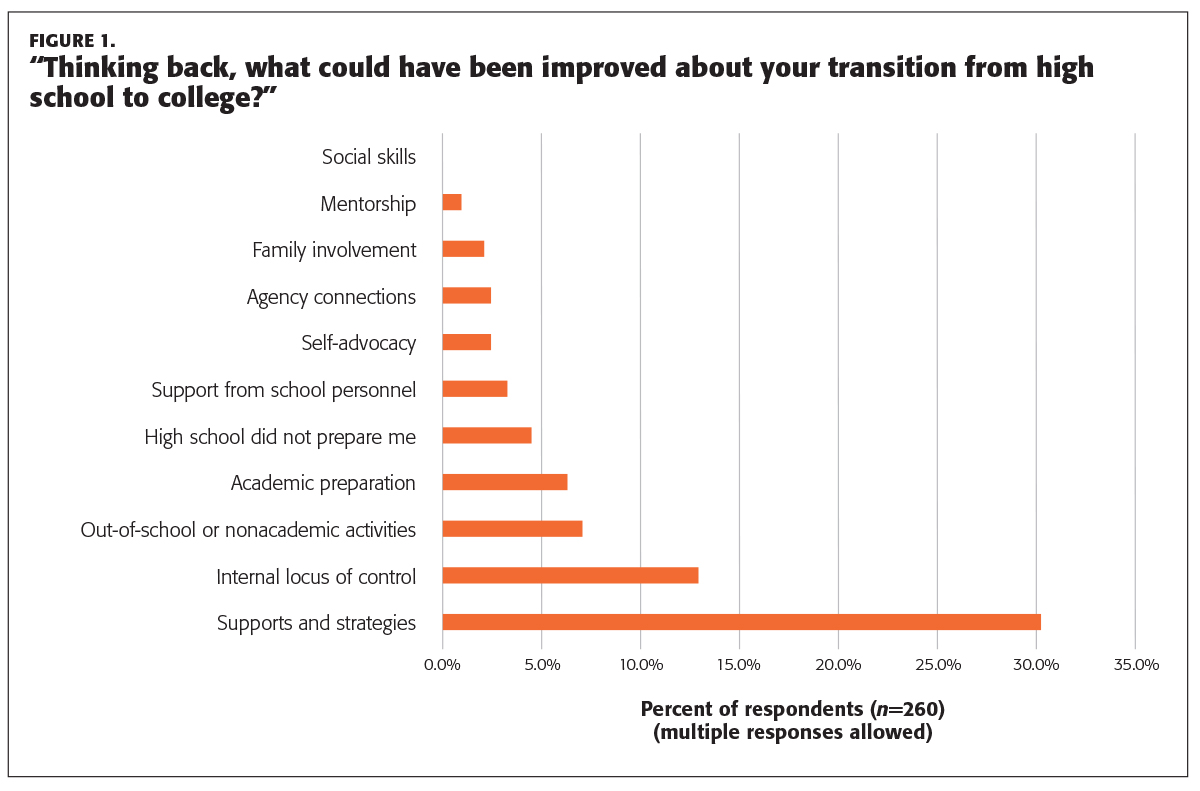

Respondents regretted that their disabilities had not been identified in high school, and about 30% indicated that to succeed in college, it is critical to seek resources and supports to develop good study and self-management skills (see Figure 1). Many believed that they went undiagnosed in high school mainly because they weren’t aware that their (relatively hidden) disabilities qualified them for services and supports. For example, one student wrote that it would have helped to “be informed that disability services applied to those with psychological disorders like anxiety and depression.” Recounted another, “In high school I wasn’t even aware that any kind of help was available for people with migraines. I actually found out about disability resources from a professor once I was already in college. I wish accommodations and disability services were talked about more in high school.”

Similarly, many respondents noted how valuable it would be for students to receive information, while still in high school, about the supports and resources that might be available to them in college. As one respondent put it, “Since I had no accommodations in high school, I had no idea I could get them in college. I did not register for [disability student services] until my 2nd year.” Typical recommendations included, “Learn about the disability program at the university you choose. It will help you a lot to get the help you need to succeed” and “speak with [college] advisers while still in high school.”

Self-determination

Consistent with previous findings about the need for students with disabilities to cultivate their self-determination (Field, Hoffman, & Posch, 1997; Kohler & Field, 2003), survey respondents strongly suggested that high school students develop their self-awareness and understanding of their disabilities. For example, wrote one student, “If I had known that my disability was not my fault, I could have stopped feeling guilty, had a higher GPA, and not felt self-hatred and isolation.” Many respondents observed that nothing was more critical to their success in college than having developed their own internal locus of control (the belief that they can influence events and their outcomes) while in high school. As one student wrote, “I don’t think anyone — neither my family nor academic counselor — expected me to go to college. So that expectation might have affected things [if not for my own determination].”

These comments clustered around concepts related to having confidence in oneself, exhibiting hard work, persevering in the face of difficulty, and having a sense of direction and passion. Said one respondent, “Personally, I would tell [high school students] not to be ashamed or embarrassed, and not to wait. I never [sought] out help because I was ashamed of my test anxiety. It was only in college that I finally decided to seek help.” Said another, “The greatest skill that helped me get through high school was a sense of motivation which ultimately led to a sense of pride, and for any student, feeling a sense of pride is one of the greatest feelings in the world.”

Student success skills

When asked about the skills they had acquired in high school that were most important to their success in college, most respondents named competencies related to organization, goal setting, and study strategies — their recommendations align closely with recent research findings in this area (e.g., Getzel & Thoma, 2008; Gil, 2007; O’Neill, Markward, & French, 2012). In order of magnitude, they mentioned such study skills and strategies as time management, help seeking, task management, test taking, note taking, finding out how disabilities affect learning, enlisting support from peers, and attending class.

Particularly important, respondents said, were actions and attitudes that reinforce one’s awareness of oneself as a learner, including habits such as “getting work done on time and keeping up with the work being assigned” and “getting help from mentors from freshman year all the way through senior year.” Noted one student, “Implementing a class which teaches students how to effectively study, take notes, and excel in one’s college courses would be invaluable.” Said another, “Not only is it important to help high school students apply for colleges and financial aid, [but] it’s equally important to teach them about the learning environment and how to succeed with good studying strategies.”

Some ways to support high school students with mild disabilities

Let me reiterate that, of the 260 university students with disabilities I surveyed, 81.2% had received no special education services in high school (or could not remember receiving them), which raises important questions about how best to reach the many students who currently slip through the cracks, going undiagnosed and underserved by our secondary schools.

Many respondents noted how valuable it would be for students to receive information, while still in high school, about the supports and resources that might be available to them in college.

Given that many of our school systems are constrained by large class sizes, tight budgets, and shortages of special education teachers, counselors, and psychologists, it may not be realistic for all of these students to have an IEP or 504 plan. For example, in the city where I conducted this survey, the public high schools have about one counselor for every 400 students. Surely, though, students with milder disabilities deserve some level of support. In that case, what can we do to prepare them for the transition to college?

To identify students with relatively mild disabilities, some districts have relied on a Response to Intervention (RTI) model, which emphasizes progress monitoring and instructional interventions prior to a special education referral (Canter, 2006). But for students who continue to fall under the radar, or who do just well enough to get by, other measures must be taken.

According to respondents to my survey, one option is for high schools to provide all students with information about disabilities — including relatively mild ones — and to do so frequently, ensuring that those who are not enrolled in special education receive certain key messages. This includes basic information about the range of disability types that qualify for support in college and how to access these resources. Further, all students (particularly high school juniors and seniors who are thinking about next steps after graduation) will benefit from instruction in study skills and self-advocacy, which encourage them to seek out services, set goals, carefully manage time, and use problem-solving strategies in both school and college courses (Janiga & Costenbader, 2002; Morningstar et al., 2010; Thoma & Getzel, 2005).

Similarly, the 2016 PDK poll results emphasized the need for schools to help all students develop interpersonal skills such as cooperation, respect, and persistence (Richardson, 2017), which are critical to postsecondary success. This isn’t likely to be as effective as providing several years of special education services, but it can make a critical difference to some students.

Finally, even where resources are scarce, high schools can provide staff development opportunities to increase awareness of often-misunderstood disabilities such as ADHD and social anxiety. Schools can also do more to encourage regular classroom teachers to integrate the teaching of time management, self-advocacy, and study strategies into the general education curriculum. And many schools can take better advantage of collaborative efforts to link secondary schools and college campuses, such as summer bridge programs, near-peer mentoring programs, and campus visiting programs, which have been found to improve students’ understanding of the differences between secondary and postsecondary settings (Burgstahler & Crawford, 2007; Connor, 2012).

References

Burgstahler, S. & Crawford, L. (2007). Managing an e-mentoring community to support students with disabilities: A case study. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education Journal, 15 (2), 97-114.

Canter, A. (2006). Problem solving and RTI: New roles for school psychologists. Communiqué, 34. www.fehb.org/CCSE/CCSEConference2017/ProblemSolving-RTINewRolesforSchPsych.pdf

Connor, D.J. (2012). Helping students with disabilities transition to college. Teaching Exceptional Children, 44 (5), 16-25.

Field, S., Hoffman, A.M., & Posch, M. (1997). Self-determination during adolescence: A developmental perspective. Remedial & Special Education, 18 (5), 285-293.

Getzel, E. & Thoma, C. (2008). Experiences of college students with disabilities and the importance of self-determination in higher education settings. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 31 (2), 77-84.

Gil, L. (2007). Bridging the transition gap from high school to college: Preparing students with disabilities for a successful postsecondary experience. Teaching Exceptional Children, 40 (2). 12-15.

Janiga, S.J. & Costenbader, V. (2002). The transition from high school to postsecondary education for students with learning disabilities: A survey of college service coordinators. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35 (5), 462.

Kohler, P.D. & Field, S. (2003). Transition-focused education: Foundation for the future. Journal of Special Education, 37 (3), 174-183.

Morningstar, M.E., Frey, B.F., Noonan, P.M., Ng, J., Clavenna-Deane, B., Graves, P., . . . & Williams-Diehm, K. (2010). A preliminary investigation of the relationship of transition preparation and self-determination for students with disabilities in postsecondary educational settings. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 33 (2), 88-94.

O’Neill, L.N., Markward, M., & French, J. (2012). Predictors of graduation among college students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 25 (1), 21-36.

Raue, K. & Lewis, L. (2011). Students with disabilities at degree-granting postsecondary institutions (NCES 2011–018). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Richardson, J. (Ed.). (2017). The 49th annual PDK poll of the public’s attitudes toward the public schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 99 (1), K1-K31.

Shaw, S.F. & Dukes, L.L. (2013). Transition to postsecondary education: A call for evidence-based practice. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 36 (1), 51-57.

Tesch, R. (1990). Qualitative research: Analysis types and software tools. New York: Falmer.

Test, D.W., Fowler, C.H., White, J., Richter, S., & Walker, A. (2009). Evidence-based secondary transition practices for enhancing school completion. Exceptionality, 17 (1), 16-29.

Thoma, C.A. & Getzel, E.E. (2005). “Self-determination is what it’s all about”: What post-secondary students with disabilities tell us are important considerations for success. Education & Training in Developmental Disabilities, 40 (3), 234-242.

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights. (1995) The civil rights of students with hidden disabilities under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2009). Higher education and disability (GAO-10-33). Washington, DC: Author.

Citation: Schechter, J.S. (2018). Supporting the needs of students with undiagnosed disabilities. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (3), 45-50.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julia Silverman Schechter

JULIA SILVERMAN SCHECHTER is a completion coach at South Seattle College and the founder of College Access Now.