Cable news was stingy with its initial coverage of last week’s tragedy in Kentucky, but other outlets published stories suggesting school shootings are common and increasingly frequent. (They’re not.) What’s a reporter to do?

By Alexander Russo

Gun violence erupted at Marshall County High School in Benton, KY, last week. Two students were killed. At least 16 students were injured, though not all of them due to gunfire. A 15-year-old student is alleged to have been the assailant.

It was a terrifying event. As in the past, however, questions began emerging almost immediately over how the media covered it – issues including media accuracy, context, and editorial decision-making that are relevant to education journalism overall.

An examination of the coverage reveals that the small-town high school shooting was not initially given the national attention it warranted, especially on cable news. But the coverage that appeared in the following days was exaggerated, suggesting that school shootings like the one in Kentucky are common and increasingly frequent.

“Gunfire ringing out in American schools… seems to happen all the time,” stated a New York Times piece.

But that’s not what’s really happening in schools, according to experts and government data sources. And this approach to covering school gun violence generates inflated fears among readers and discredits professional news.

This is awful. It’s also sadly a sadly familiar media blind spot. Everytown, the school shooting data source being used by news outlets covering school shootings, was debunked by the Washington Post in 2015.

The Times, of course, says it stands by its story.

Screen grab of CNN coverage of the January 23rd school shooting in Kentucky.

Coverage of past school shootings has been marked by criticism that it unintentionally glorifies the shooter or traumatizes survivors.

In these regards, journalists covering the Kentucky high school shooting seemed to have done better, according to EWA’s Emily Richmond. She shared timely school shooting coverage advice last week

However, there were several other concerns that emerged from last week’s coverage.

Initially, the national media seemed to be downplaying the school shooting in Kentucky. On Twitter, former AP education reporter and Obama education press secretary Dorie Turner Nolt blasted cable news for not covering the story.

Dear @CNN, @MSNBC: Two people are dead and 17 people are injured in a school shooting in Kentucky. Why are you on air about this? These are children. #benton #KentuckySchoolShooting

— Dorie Turner Nolt (@dorieturnernolt) January 23, 2018

Bruce Shapiro, who heads the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia University, said he saw skimpy national coverage without much time or energy being put into the reporting. “We’ve reached a sad state in the national news cycle when a body count in a school shooting is deemed to be too low to merit more than passing coverage.”

According to the liberal-leaning Media Matters for America, major cable news stations devoted a scant 16 minutes of coverage to the Kentucky shooting. MSNBC covered the shooting for just over a minute – the least of all the cable news channels tracked by the organization.

The muted initial response to the Kentucky shooting became a story of its own.

One AP story focused on whether the public has become numb to school shootings. NPR’s Scott Simon asked if the news of students being killed at school had “lost the power to shock and sober us?”

“We’re barely moved to tweet,” wrote The 74’s Steve Snyder.

New York Times story reporting 11 school shootings in first three weeks of 2018

The American public may be inured to news of all but the most extreme kinds of gun violence. If so, however, last week’s coverage shows that the media may have played a role in numbing its audience.

In the days following the Kentucky shooting, several news outlets jumped into the fray by grouping gun incidents at schools in ways that were overly broad and unhelpful, using a data source that’s clearly misleading and known to be flawed.

The most vivid example: a New York Times story claiming that the Kentucky incident was the 11th school shooting in 2018.

The Times story didn’t just mention that the Kentucky shooting was the 11th incident. It put the number in its headline.

But that’s not really what’s been happening.

As the Times acknowledges further down in the story, there weren’t 11 incidents in which kids got shot or killed during the first three weeks of 2018.

The number being used comes from an organization called Everytown, an organization funded by former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg and dedicated to gun safety. Everytown counts gun-related incidents that take place at schools, including shots fired at or near a school, accidental discharges of weapons, suicides, and events that take place overnight.

Most of these don’t match what the public probably imagines when it sees the words “school shooting.”

Three years ago, the Washington Post fact-checked Everytown’s methods and gave claims based on its data a whopping four Pinocchio’s. “It is difficult to see how many of the incidents included in Everytown’s list…would be considered a ‘school shooting,’” noted the Post. The statistic, repeated in a speech by US Senator Chris Murphy, was named one of the top misstatements of the year.

The use of these numbers raised immediate red flags.

“I have a real concern when the media tend to cite statistics like 11 school shootings in three weeks,” says Northeastern University criminology professor James Alan Fox, whose book about mass violence is coming out next week. “The problem is that ‘shooting’ is a broad term” that could mean all sorts of things,” says Fox.

Fox advocates focusing on the numbers of school-based homicides, which is captured in federal data. According to the latest information, there were 48 school-associated violent deaths from July 1, 2013, through June 30, 2014, including incidents that involved guns and those that didn’t.

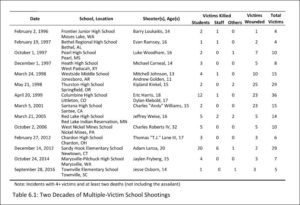

Even more helpful, according to Fox, would be to focus attention on multiple-fatality events. According to a table Fox provided to The Grade, there have been 14 school shooting incidents involving multiple victims (defined as four or more victims and at least two deaths not including the assailant) during the 20-year period between February 1996 and September 2016.

Unpublished table from Northeastern professor James Alan Fox showing multiple-victim school shooting incidents, 1996-2016

By this kind of definition, the Kentucky killings would be the first and only school shooting of 2018, not one of 11.

Others might not go so far in narrowing reporting of school shootings, but Fox is not alone in his criticisms of the numbers being used by outlets like the Times.

“In my opinion, it’s misleading to say that there have been 11 school shootings since January 1,” The Trace’s Jennifer Mascia said via email.

“Shame on newsrooms for giving this clearly inflated number oxygen,” blasted the right-leaning Washington Examiner.

Asked about its approach to counting school gun incidents, a representative from Everytown sent an explainer in which it is noted that efforts to define school shootings more narrowly have “discounted the lives of African American students and other students of color who were affected by gun violence in their schools.”

Asked about the use of the Everytown statistic in its coverage, Times national editor Marc Lacey said via email that “The Times cited all incidents of shootings that took place on school property so far this year, which currently stands at 11. This is an important issue of public concern and we are proud to shine a light on it.”

_

It’s not just that the Times exaggerated the number of school shootings that have taken place this year. The news outlet also suggested that gun incidents in schools have – seemingly – become commonplace.

To be sure, there have been a handful of horrific school shootings over the past 20 years, including the Sandy Hook elementary school massacre. A 2016 Government Accountability Office report found that nearly 20 states required schools to have active shooter plans, and two-thirds of school districts reported that they had conducted active shooter exercises. A Gallup update on school shootings notes that nearly a quarter of US parents fear for their children’s safety at school. Nearly 40 percent of Americans worry about being a victim of a mass shooting.

But familiarity with gun violence, public fears, and the spread of preventative measures don’t actually mean that school shootings are commonplace or necessarily on the rise. It’s not at all clear that they are. And, relatively speaking, schools remain safe.

“There are many, many shootings every day in the United States,” says University of Virginia professor Dewey Cornell, who studies youth violence and was also critical of news outlets reporting 11 school shootings in three weeks. Cornell cites CDC data showing 300 shooting incidents a day where someone is injured or killed. “Schools are relatively safe places compared to other locations.”

In fact, a 2015 New York Times examination of media coverage of the Columbine high school shooting found that, while many people assume mass school shootings are happening ever more frequently, “shooting homicides in schools have held fairly steady across the last two decades.”

Here’s how The Trace covered last week’s school shootings.

The sad fact is that there is likely to be another school gun incident in the near future in which students will be injured or killed.

There is no single perfect way to describe school shooting incidents.

“Federal and state statistics tend to grossly underestimate the extent of school crime and violence,” said National School Safety and Security Services Ken Trump in a 2015 Post article. “Public perception tends to overstate it.”

So what are the options for reporters who don’t want to be alarmist but want to keep readers informed?

One approach would be to focus narrowly on school shootings that involve injuries or death, along the lines Fox recommends.

The Trace, a nonprofit outlet focused on covering gun violence, reported that America has had three school shootings in two days – excluding incidents that didn’t involve harm to students or teachers on campus during the school day.

There are obvious problems with this approach. Everytown calls this “whitewashing” school gun violence. Former Obama education press person Turner Nolt says “You walk a very precarious line if you try and determine what is and what isn’t a school shooting.” These are good points. But the alternative – using “school shootings” as an umbrella term for any and all gun-related incidents on campus – is equally problematic.

Another approach would be to clarify for readers how the numbers are counted from the very start, so that they can understand what’s being communicated.

Organizations like Everytown could start breaking out different kinds of gun incidents for schools – one for the broad, all-inclusive category that’s used now, a second injury/fatality category that matches what I think most people imagine when they see the words “school shooting,” and a third category that would be reserved for Columbine- and Sandy Hook-level events.

After all, it’s not that parents and readers don’t want to know about gun-related events on campus like suicides, accidental shootings, and pellet gun incidents. Parents want to think of schools as places safe from deadly violence. People bringing guns to school creates a potentially deadly situation.

Whatever approach news outlets take, they need to be clear and consistent about what they’re reporting when it comes to school gun violence, notes EWA’s Richmond. “It’s important that we use consistent terminology and metrics, not undercounting, miscounting, or improperly amplifying information.”

The 74 is going to start tracking school shootings starting in February, according to Snyder. The outlet will be “tracking incidents on school property where gunfire wounds or injures students,” he says. “A casualty would have to be involved.”

Related columns:

How the media botched coverage of the Columbine school shooting

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/