The Parkland school shooting may force the media to reconsider its reluctance to share disturbing images of dead or injured Americans.

By Alexander Russo

There are graphic images of dead and injured students and teachers from the Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school shooting out there – gruesome crime scene photographs and disturbing images captured by students and others who were on campus during the shooting.

Most of us just haven’t seen them.

Early on during the Parkland shooting, cable news shows were uncertain whether to show a frightening but not gory video of kids cowering in the corner with gunshots firing nearby. Some of us might have seen an image of a foot and a pool of blood if we looked around on our own.

That’s about it. And if mainstream media follow old patterns, they may never share much more than has already been published.

But avoiding or limiting graphic images in gun violence journalism seems squeamish and outdated, according to a small but growing chorus of voices — and may need some serious rethinking given the current role of social media.

Without these awful images, unsettling as they may be, the American public is likely to remain unclear about the impact of school shootings and gun violence in general. The horror remains in our collective intellect and imagination, without the raw power to make it real and visceral.

And in this social media age, restraint by mainstream news outlets doesn’t mean graphic images won’t be seen by large numbers of people anyway – though not in any careful way.

For better or worse, more Parkland images are likely to get out. The only question is whether news outlets will sit on their hands when that happens or help readers understand what they’re seeing.

.

Writing about gun violence and/or urging consideration of new approaches (clockwise from top left): Fishman, Fagone, Wing, and Bouie.

Gory images of violence are commonplace in popular culture. Vivid descriptions of death and injury are increasingly frequent in mainstream journalism. But graphic images remain rare — all the more so if they are American children.

“Images of dead American youth are generally considered taboo,” said Jessica Fishman, a UPenn researcher who has studied media representations of graphic violence.

The conventional practice of avoiding these kinds of images is entirely understandable. Publishing them opens news outlets to accusations of glorifying violence, traumatizing survivors, and practicing clickbait journalism.

However, a handful of voices have emerged in recent weeks urging reconsideration of the near-ban on graphic images of gun violence, with some of those opinions coming from unlikely quarters.

A New York Times op-ed from the father of a previous school shooting victim wondered if “perhaps the time has come to use” graphic pictures he and other parents have of their dead children.

A doctor who treated some of the victims of the Parkland massacre wrote in The Atlantic that seeing the damage high power weapons do to human bodies would change the gun debate.

In Show the Carnage, Slate’s Jamelle Bouie wrote, “For the public, mass shootings are bloodless… We don’t see what the bullets actually do.”

“The media’s refusal to show this reality makes us complicit,” tweeted Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones.

In nearly all cases, those who urge reconsideration of the prohibition against ghastly images cite a handful of well-known instances in which such images presented by news outlets are said to have played an important role, including those of Emmett Till’s body in an open casket, body bags during Vietnam, and the video deaths of Philando Castile and Mike Brown.

These opinions add to a discussion that has been bubbling up in the past year or so, as journalists struggle to figure out how to describe the damage that guns do — without actually showing it.

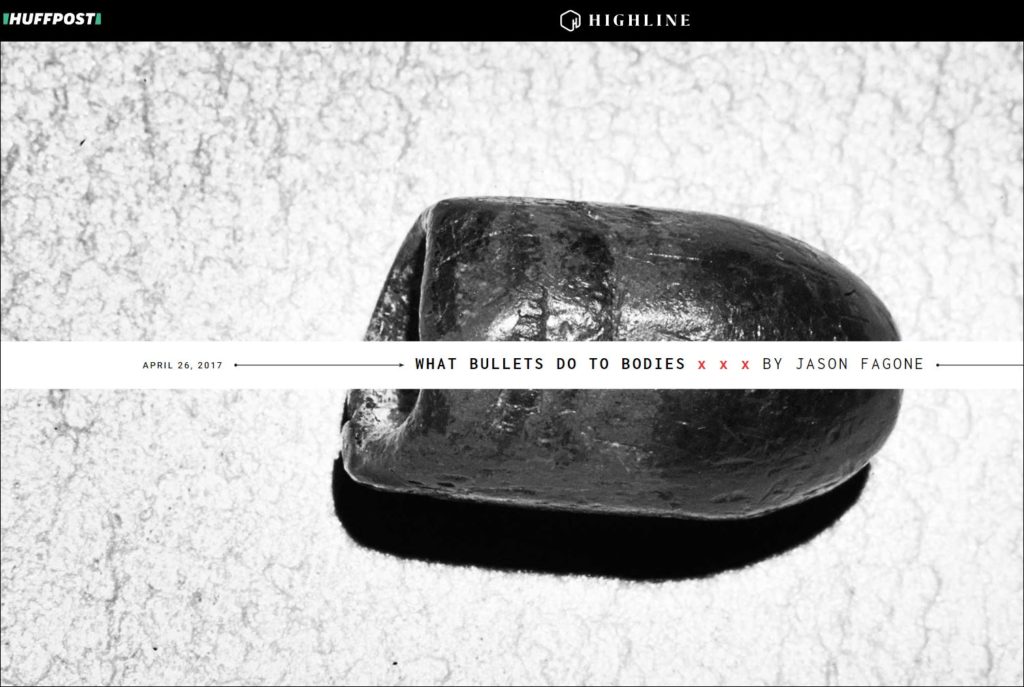

A HuffPost Highline story from last summer headlined What Bullets Do to Bodies detailed the consequences of gun violence in and around Philadelphia, based in part on a graphic Temple University slide show.

According to reporter Jason Fagone, the impetus was to give readers information about gun violence that “hasn’t really been represented in media — or only very occasionally.” But he had to accomplish his goal without images from the slideshow.

Another recent HuffPost story, Las Vegas Autopsies Reveal The True Brutality Of Mass Shootings, noted that, in the absence of such gruesome detail, “media coverage often serves to sanitize the graphic, uncomfortable reality of these tragedies.”

That story did not include images of the victims, either. Reporter Nick Wing says he was trying to be respectful of the victims, rather than ghoulish or shocking. He also lacked access to the autopsy images. “If we had had access to the images, it would have been a much more complicated conversation.”

“The societal norm has been that those are protected images,” says Wing. “But I think that’s starting to change.”

Two recent attempts to write about gun violence without using graphic images (HuffPost Highline and NYT)

In truth, U.S. mainstream media has long been inconsistent about the use of graphic imagery and death, depending on the nationality and race of the person being depicted.

The photograph of a dead Syrian child on the beach was widely used by mainstream news outlets to illustrate the plight of refugees, notes Fagone, who thinks there may be a double standard at play. “A dead American child from a shooting is something you never see.”

According to Fishman, who interviewed numerous newsroom photo editors as part of her work, international tragedies occasionally include unsettling depictions of death and destruction, but “pictures documenting American bodies are actually condemned for being disturbing.”

Mainstream media outlets are especially reluctant to depict graphic violence when the victims are American, says Fishman, author of the new book, “How News Media Censor and Display the Dead.” “Virtually all images of dead youth [found in her research] showed non-American victims.”

As an example, she cites images of Russian children who were killed during a terrorist attack in 2004. In that case, “photojournalists and their editors decided that Americans should see the bloodied, lifeless little victims.”

According to Fishman’s research, news editors aren’t entirely aware of these inconsistencies but are under tremendous pressure not to disturb readers or be accused by other journalists of disrespecting the dead or glorifying the violence.

During the first 14 days of Katrina coverage, the Boston Globe included no photographs of corpses or even body bags in the stories detailing the nearly 2,000 deaths, according to Fishman’s book.

“The media coverage of the Parkland school shooting has exactly matched the patterns documented in the book,” says Fishman.

Screengrab from iconic 1999 Columbine school shooting video

The handling of graphic images is a challenge that the media has been grappling with “for as long as photographs have been reproduced in the news,” noted The American Prospect’s Paul Waldman in a recent piece about depictions of gun violence.

“Should they show dead bodies? Is it necessary information, or is it too upsetting for audiences to see? Does it enhance or detract from the story? What principles should guide those decisions?” he asks.

Many of those in decision-making roles think the media should remain circumspect about images of violence and death.

“I’m not opposed to showing blood and, on rare occasions, a dismemberment, if it’s integral to telling a story,” said James Estrin, a senior photographer at The New York Times. His quote was in a 2013 NY Observer article about the controversial depiction of a Boston Marathon bombing victim with severe wounds to his lower legs, being wheeled away from the area. “It’s so graphic,” he said. “I’m not sure the graphicness advances the story.”

The disincentives for publishing graphic images – upset readers, distraught survivors and family members, and criticism from other journalists – are many. Indeed, most of the expert advice out there, and most of the professional journalists interviewed for this piece urge caution.

For some, depicting images of gun violence is a non-starter. For others, it’s a gray area. Are the people identifiable? Did they survive? What does the family say? Is the photograph explicit – showing wounds – or is it understated – showing blood on the ground?

“Do the images show us anything that we do not already know?” asks Poynter’s Al Tompkins. If they do provide new information, “those images might be much more defensible.” If not, then they’re just causing pain and suffering, he says. “We already know what a body looks like when it’s shot and bleeding.”

“I don’t think adding gore to the mix would help” public understanding of gun violence, says journalist Dave Cullen, who wrote a book about the Columbine school shooting: “If anything, it might deaden us to the images.”

Just this past weekend, a New York Times article specifically focused on the damage caused by high-powered weapons was accompanied by black and white x-rays.

Voices of caution: Shapiro, Tompkins, Cullen

There’s even greater distaste for showing the outcome of school shootings because vulnerable kids and grieving parents are involved.

“We never would show a dead 14-year old,” said a reporter who did not have permission to be interviewed. “I don’t think anyone can justify using an image of a child who has been murdered.”

If anything, the media has become more cautious about depicting violence in recent years, says Columbia’s Bruce Shapiro, who heads the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma. “I think that American journalists right now have a deep-seated concern about treating survivors of violence ethically and not exploiting people through images just for ratings and clicks.” It’s not always possible to avoid harming those who have been afflicted by a violent event, said Shapiro, but journalists are trying to be more mindful. “Minimizing harm to victims is an important part of the journalism equation.”

Even for those who are open to the idea of graphic images in stories about gun violence, however, there’s the concern that nobody can predict which image will have the most impact. Says Shapiro: “You can never know ahead of time what that image is going to be.”

Here’s more advice about covering mass shootings and making tough choices from Poynter, the Education Writers Association, and the Dart Center at Columbia.

Screengrab of scary but not gory student video shared on social media and by some news outlets. Click here to see and hear it.

Two things are new and different in 2018: The concern about gun violence has reached a such a high level that it’s still being written about three weeks after Parkland.

“Images are important to convey the horror of gun violence,” said one reporter who’s written about gun violence for a national news outlet. “A lot of people don’t understand the reality of what guns do to children.”

And non-journalistic websites and social media play an ever-bigger role in shaping public understanding of the world.

“Parkland students posted videos of the massacre online to expose the tragedy, but news editors rejected the graphic images,” UPenn’s Fishman said in an email interview. “It is as if the students want the world to see something that the news media do not.”

Given the high levels of concern and interest around gun violence, media outlets ought to rethink their overly cautious ways.

Ideally, they would consider including graphic images as an integral part of the story, using careful presentation so that readers understand what they’re seeing and so that the potential damage to survivors and families is minimized. They should ask themselves whether a photograph adds add depth and feeling to the storytelling, or whether it simply exploits a situation and caters to morbid curiosity.

Done thoughtfully, the presentation of difficult images could have an enormous impact on public understanding of gun violence and school shootings.

The alternatives – ignoring the existence of troubling images, or sticking to images of running kids and candlelight vigils or even x-rays – don’t add to the nation’s understanding of mass shootings and ducks the role that mainstream journalism should play.

Articles cited in this column:

NYT: Wounds From Military-Style Rifles? ‘A Ghastly Thing to See’

Slate: Show the Carnage

NYT: A Message From the Club No One Wants to Join

NYT: 250 Die as Siege at a Russian School Ends in Chaos [Beslan school siege ten years later]

NY Observer: Graphic Bombing Photo Divides Media

Nieman Reports: Dead Bodies, Nationality, and the “Newsworthy” Image

The American Prospect: What the Parkland Students Wanted the World to See—But the Media Didn’t

HuffPost: Las Vegas Autopsies Reveal The True Brutality Of Mass Shootings

The Atlantic: What I Saw Treating the Victims From Parkland Should Change the Debate

Related writing: Misleading coverage of school shootings in 2018

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/