A long-forgotten uproar illustrates some of the chronic failures of media outlets covering polarized, racially charged situations. But it’s not just a historic concern. The controversy could re-emerge any time now, as schools search for better ways to serve low-income students.

By Alexander Russo

On December 18, 1996, the Oakland (CA) school board passed a two-page resolution that highlighted the plight of African-American students in the district and — as part of a plan to improve their academic success — claimed that African-American English spoken by many students was its own language and should be used to help children learn standard classroom English.

The notion generated enormous attention and controversy at the time, the vast majority of it critical. Nearly everybody – Jesse Jackson, the New York Times editorial page, Clinton education secretary Richard Riley, Maya Angelou – all came out against what Oakland was proposing, which had been dubbed “Ebonics.”

“One school board, in one city, passed one little resolution,” writes Michael Hobbes in a 2017 HuffPost Highline piece revisiting what happened. “And the rest of the country spent the next six months freaking out about it.”

In response, the district rolled back its plans. The superintendent left soon thereafter. And districts haven’t dared to try anything similarly dramatic in the 22 years that have passed since then.

As it turns out, however, the main thrust of the Oakland proposal was overwhelmingly supported by linguists, and the approach it was recommending – using children’s home dialect to help teach standard English – had proven successful in other places in the past.

But the general public had little chance to grasp the larger picture. Traditional news coverage was eclipsed by hyperbolic op-eds and editorials. Cable news failed to provide any depth of understanding. Few in the general public would ever know that the district went ahead with its program under another name, or that several of those most opposed at the outset would later modify their positions. Even now, few know that the population of a group some call “standard English learners” goes far beyond African-American students or that a handful of districts have quietly created programs using their home dialects as a bridge around the country.

Revisiting the controversy provides an excellent opportunity to look at the strengths and weaknesses of media coverage of the Oakland proposal and its impact on subsequent efforts to address the needs of what some now call “standard English learners” in American schools.

The story is not merely a historical concern. To help meet their needs, a handful of districts and schools have quietly returned to the idea of using students’ home dialects to help them learn standard English.

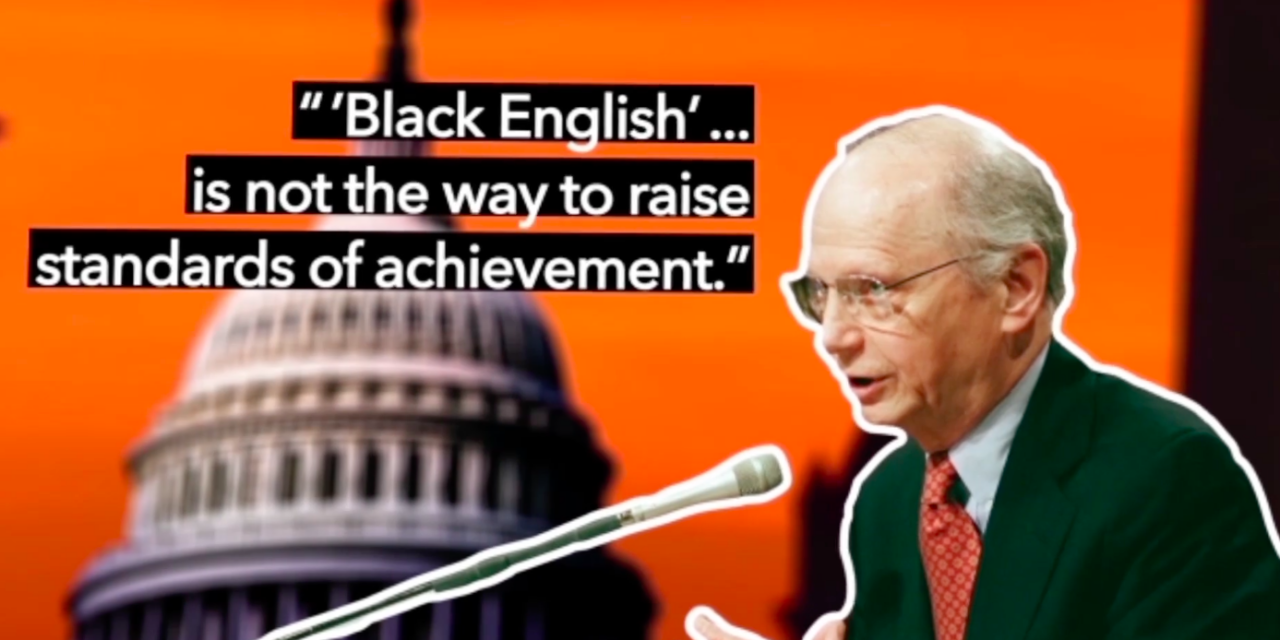

Screengrab from HuffPost video showing Clinton education secretary Richard Riley

The problems the Oakland school board was trying to address were serious ones. Just over half the kids in the Oakland were African-American – the largest portion of any California district. But they weren’t, as a group, being treated well in the existing education system. They received 80 percent of suspensions and made up 71 percent of kids with special education referrals. Their average grade point average was D+.

Then as now, the use of vernacular English spoken by some African-American students was corrected as “bad” in most classrooms. It was generally treated as a lower form of English that limited its speakers’ chances for academic and professional success.

The thrust of the Oakland plan was to teach standard English by contrasting it with African-American English. This approach had been shown to be successful in a pilot program in the district, as well as in a handful of other districts in the past.

In practice, the program piloted in Oakland was not nearly as radical as it might have sounded. Michael Bazeley, who was the education reporter for the Oakland Tribune at the time, visited a few classrooms where it was being used. “They very clearly were not ‘teaching’ students Black English or Ebonics,” he said. “They were acknowledging that Black English was real and using it as a bridge to standard English.”

But deep feelings of concern and guilt over the treatment of African-American children in schools is always near the surface in this country. The notion of “code-switching,” in which individuals learn to toggle back and forth between standard spoken English and another dialect, wasn’t nearly as familiar as it is today.

And, in what would prove to be extraordinarily distracting assertion, the Oakland resolution mistakenly declared that African-American English was its own language, rather than a dialect of English.

While many thought it was an effort to secure federal bilingual education funding, the claim was an unintentional error on the board’s part, according to some of those involved at the time. “They weren’t linguists,” according to Darolyn Davis, who handled crisis communications for the district during that period. “They didn’t use the word ‘language’ from a linguistic point of view.”

But that error – and resolution language referring to a “genetic” basis for African-American English that may also have been mistaken – would expose the board and the idea they were proposing to enormous criticism and ridicule, generally overshadowing the plight of African-American students in Oakland schools and the merits of the classroom approach being proposed.

The dominant narrative soon took shape that Oakland was trying to dumb down education by accepting Black English as a legitimate language of its own, and even teaching it to students. Oakland teachers were going to use street slang in the classroom or allow students to talk or write using it instead of standard English. The idea was pandering, political correctness run amok, and a sneaky attempt to win additional funding to boot.

NYT editorial page opposing the Oakland plan

Almost immediately, editorial pages, oped sections, and talk shows were all over the story.

The Ebonics controversy was “Topic 1 on radio talk shows across the country,” notes Gene Maeroff in his book, “Imagining Education: The Media and Schools in America.”

Jesse Jackson came out against it on NBC’s Meet The Press. The New York Times editorial page denounced what it described as “linguistic confusion.” Cable news hosts like Rush Limbaugh warned that “we be happy” was going to be taught alongside Shakespeare. Frank Rich, a New York Times columnist at the time, called the school board “deranged” and the resolution an “incendiary separatist manifesto.” There was even a Doonesbury comic strip.

“I don’t even want to say it was mixed,” says William Brennan about what he saw in his reporting for The Atlantic. “For every good article on the subject there were just 10 that were useless and furthered misunderstandings about the topic and language in general.”

“Nobody made an effort to actually figure out what the school board was doing,” says the HuffPost’s Hobbes. “Everyone went with this cartoon version of what they were doing.”

To its defenders, Ebonics was a legitimate program being proposed by a largely black school board and attacked by a mostly white media establishment. To its critics – including middle-class African-Americans and black celebrities like Maya Angelou – it was a mistaken idea that would set kids back rather than launching them forward.

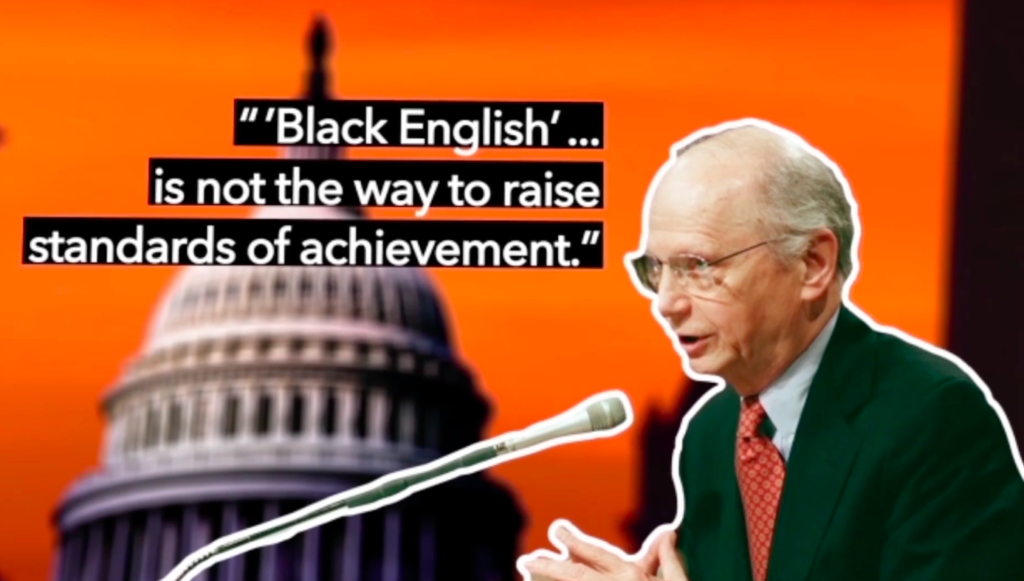

NHSA ad against the use of Ebonics in schools.

By and large, the news coverage of the Oakland proposal was unobjectionable, if ineffective at generating much attention.

The Oakland Tribune’s Bazeley wrote a pretty straightforward front-page story about the program, which he observed in action. “I believed at the time that the criticism was overblown because most people had a distorted view of what was happening in the classroom,” says Bazeley.

And the NYT’s Peter Applebome wrote a series of pieces about the controversy, fleshing out Oakland’s distinct place in California politics, the political dynamics surrounding the vote in favor of the resolution, and a controversial figure who seemed to be behind the Ebonics proposal.

One exception noted by several of those interviewed is Jacob Heilbrunn’s piece in The New Republic, which blended opinion and reporting.

But reporting some of these news stories took time – Applebome’s deepest piece didn’t come out until March – and was generally produced by reporters who were not familiar with English dialects or the history of programs to help dialect speakers learn the dominant form of the language.

And the distinction between news and opinion, which is so obvious and important to journalists, is not nearly as clear to non-journalists who tend to lump opinion and news together if it’s being published by the same outlet.

News stories written at the time weren’t nearly powerful or timely enough to compete with the wave of opinion writing and cable news. In a recap of his experience at the time, Stanford linguist John Rickford criticized the media for promoting a simplistic narrative. “The media refused to focus on this massive evidence of how schools fail to teach African American students with existing methods.”

The real-world responses were just as strong. Clinton Education Secretary Richard Riley denounced the policy. The national Head Start Association put a full-page ad in the New York Times with the title “I Has a Dream.” At least one state legislature banned Ebonics from being used in classrooms. And the US Senate scheduled a hearing on the debate.

After the congressional hearing, Oakland released an updated resolution that removed every mention of the word Ebonics. And “since then, no district has tried anything that ambitious for meeting the needs of its African-American students,” writes Hobbes.

April 2018 article about African-American English in The Atlantic

Since 1996, the debate over using African-American English in classrooms has mostly gone quiet.

However, the need hasn’t gone away, and the practice of using students’ dialects as a bridge to standard English has quietly re-emerged.

That’s largely because the case for schools teaching kids code-switching remains a powerful one. Roughly a third of African-American English speakers don’t learn to code switch on their own, according to Georgia State professor Julie Washington. Students who speak both versions of English score higher than those who don’t. Those who lag behind in this area need to be taught or it may never happen. And it’s not just African-American kids who might benefit from this kind of help. The estimated 100,000 standard English Learners in Los Angeles public schools were the district’s lowest-performing students, according to a 2008 LA Daily News article.

What would happen if a district proposed something along the same lines in present times?

Many factors have changed. States no longer require teachers to pass tests showing their ability to speak standard English. It’s become somewhat commonplace for teachers to use rap music based on Black English and other dialects to engage and instruct kids. Bilingual education is much more familiar and less controversial than it was previously. And the idea of code-switching is a generally familiar one. The sense of urgency around racial justice and economic inequality is as strong as it’s been in decades. And there are no outlets and voices of opinion out there.

Georgia State’s Washington describes the Oakland resolution as mistaken and remembers the media response as an expression of racist attitudes in America at the time. And she says she was extremely nervous about participating in the The Atlantic article featuring her work and the dialect that came out earlier this month. But she believes that, after years of keeping their heads down, advocates of using the dialect to teach mainstream classroom English are re-emerging. “The dynamics have changed… The times have changed.”

However, public opinion remains deeply divided on issues of culture and race. Teaching English to kids who are born and raised in the US remains unfamiliar and is negatively associated with the Ebonics controversy. While the student population is more diverse than it was two decades ago, classroom teachers in America are predominantly white and monolingual. This population often brings with it negative judgments about dialects – which some linguists call “dominant language ideology” – based on their own experiences and culture.

And few journalists have as much time as they did 20 years ago to check out facts. Social media adds layers and dynamics that make even the most vitriolic newspaper op-eds seem quaint. Hot takes are all the rage, and opinion journalists are encouraged to be less nuanced in their approach.

“I think it would go down differently,” Brennan says about the notion of a district proposing to use African-American English in 2018, “but not necessarily more successfully.”

Primary sources:

The Atlantic: Julie Washington’s Quest to Get Schools to Respect African-American English

HuffPost Highline: Why America Needs Ebonics Now

NYT: Dispute Over Ebonics Reflects a Volatile Mix That Roils Urban Education

Education Week: Students Learn to ‘Toggle’ Between Dialects

Secondary sources

New Yorker: The Case for Black English

Rickford: The Ebonics controversy in my backyard

Rethinking School: The Real Ebonics Debate

The Atlantic: Academic Ignorance and Black Intelligence

LA Times: Oakland District Says Policy on Ebonics Misunderstood

New Yorker: Johnny Be Good

AP: Media Distort Black English Policy, Jackson Says

Washington Post: OAKLAND SCHOOL SYSTEM RECOGNIZES ‘BLACK ENGLISH’ AS SECOND LANGUAGE

NPR: Survey Raises Concerns About Non-English Speaking Students

New York Times: School District Elevates Status of Black English

Related columns from The Grade:

“Feel-Good” Philadelphia Inquirer Story Highlights Concerns About Racial Blind Spots

Just How White Is Education Journalism – & How To Encourage More #edJOC?

Fear, Complicity, & Guilt Get In Way Of Covering School Segregation, Says NYT Reporter

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/