What to do when fake news goes viral, based on last week’s now-debunked Betsy DeVos resignation story.

By Alexander Russo

Over the last week or so, the education world has gone through a roller-coaster ride of emotions over the rumored (and since debunked) notion that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos was on the verge of quitting her job.

What happened in brief is that – based largely on a single speculative quote in an otherwise balanced Politico profile – progressive outlets and critics of DeVos spread the rumor that DeVos was frustrated enough that she was about to quit.

A handful of education reporters and outlets raised as much of a stink as they knew how to raise. Nobody had produced any real evidence that such a thing is about to happen. In theory, stories don’t get much easier to debunk than this one. And eventually, the outlets involved corrected their stories.

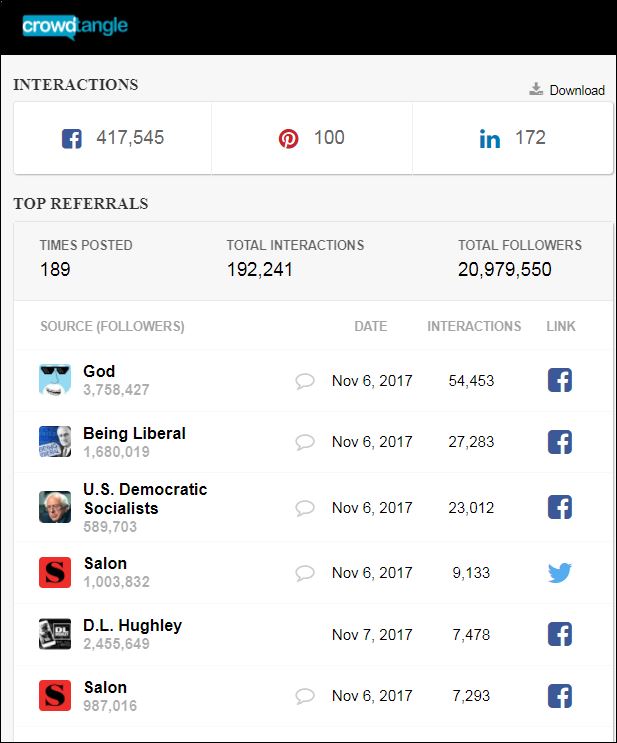

But none of these efforts prevented the rumor from going viral, including roughly 420,000 Facebook likes and shares based off a single Salon story.

“The Facebook shares on this Salon story are ridiculously high,” said Mike Caulfield, head of the Digital Polarization Initiative at the American Democracy Project. “I mean, wow.”

In the larger scheme of things, the DeVos rumor may not be all that important. But what if the story had been about something more important, changed the course of events, or caused readers to take action in real life? And what happens the next time someone claims DeVos is headed to the door?

The DeVos rumor illustrates – not for the first time – just how powerful social media can be, how susceptible traditional journalism is to what often gets called fake news, and how little journalists know (or are able) to do even after it’s been recognized.

Here’s what happened this time, and some advice from experts about what to do when it almost surely happens again.

Politico magazine’s profile of DeVos, first published November 1.

At first, Politico magazine’s profile of Betsy DeVos seemed most notable for the juicy-for-Washington tidbits reporter Tim Alberta had gleaned from three days with the controversial Education Secretary.

In the piece, headlined The Education of Betsy DeVos, the Michigan conservative explained things (like why she had persisted in visiting a school despite protesters blocking the way) and shared her feelings (that the transition team assigned to her by the White House was largely responsible for her notably godawful confirmation experience).

The overall thrust of the Politico piece was that DeVos was settling in: “Anyone betting against DeVos serving all four years of Trump’s first term… is underestimating the sense of duty and moral righteousness deeply embedded in someone who could be doing just about anything else right now,” wrote Alberta in the piece. “DeVos appears to be hunkering down and mapping out where she can maximize her impact.”

The subtext behind the Politico story suggested a certain degree of comfort on the part of the EdSec and her media team. Cabinet heads don’t usually give access to Politico journalists for long features if they’re feeling embattled or about to resign, and they don’t usually make comments that could anger White House officials unless they’re feeling somewhat confident about their position.

The image accompanying the piece – DeVos sitting at a wooden table with a green apple – looked like an old-timey portrait.

The original version of the Salon story, headlined “Officials expect DeVos to resign.”

But then, over the next week, sites like Salon and AlterNet and HuffPost repackaged the Politico story into a narrative suggesting that a frustrated DeVos was pretty close to resigning from the job.

In what would prove a brilliant move in terms of readership, Salon published the AlterNet story with the headline Officials expect DeVos to resign from Trump administration.

This new version of the story was based mostly on a single speculative quote buried deep in the long Politico story: “In Washington education circles, the conversation is already about the post-DeVos landscape, because the assumption is she won’t stay long,” said Tom Toch, a former education journalist who now runs an education think tank at Georgetown.

Almost immediately, the liberal end of social media lit up. Devos is one of the most-disliked of Trump’s cabinet members, viscerally so among teachers and many parents. There’s nothing many of her many critics would like to see than the abrupt departure of this rich, seemingly clueless Trump appointee.

Alarmed by a storyline that seemed obviously untrue, a handful of education reporters and others (I among them) tried to knock the story back. But these efforts were no match for such a juicy tale. And, as it turned out, they may have been misplaced.

Among the outlets that posted a version of the DeVos resignation piece were MassLive, HuffPost (in the form of a contributor’s blog post), and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Asked how she ended up writing about DeVos’s departure, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s Maureen Downey told me that she’d originally written something up about DeVos’s criticisms of the Trump transition team in the Politico piece, but then saw the HuffPost article about the possible resignation and slipped that in. The possibility DeVos would leave so soon didn’t seem like a stretch to her. “Nothing would surprise me at this point,” she said in a recent phone call. “Anything can and will happen.”

However, most of the traffic was being produced by social media.

As of yesterday, the Salon version of the story had racked up a whopping 417,000 likes on Facebook. (A Yahoo! version of the story spread widely as well, much of it on Reddit.)

The top points of distribution for the Salon story were Facebook pages called The Good Lord Above and Being Liberal. The top distribution sites for the Yahoo! version of the story were subreddits for politics and teachers.

Relatively little of the sharing was going on via Twitter.

CrowdTangle report showing more than 400,000 Facebook interactions and nearly 21 million social media accounts reached from the Salon story alone. (For an explanation of “total followers,” go here.)

Fake news and its many cousins have been a frequent topic of conversation among journalists and journalism watchers over the past year and a half.

Among those involved in trying to address the spread of disinformation are First Draft News, BuzzFeed’s Debunked, the Washington Post’s Abby Ohlheiser, Snopes, PolitiFact, and NewsWhip (a paid service). The topic is concerning enough that the Nieman Lab runs a weekly column about it called Real News About Fake News. Poynter operates an International Fact-Checking Network.

Though commonly associated with the alt right and Russian hackers, disinformation is not just problem among conservative outlets. In structure and in its willingness to pass along stories that stretch the facts, the network of liberal blogs and Facebook pages parallels the conservative version.

It’s worth noting that many of those involved in the disinformation debate don’t like the term fake news, which can obscure differences among different kinds of stories and has been turned into a partisan epithet.

By a strict standard, the DeVos resignation rumor wasn’t really fake news, in that it wasn’t created out of thin air, according to Peter Adams, senior VP of education for the News Literacy Project. It was irresponsible journalism on the part of Salon, creating a clickbait headline and sensationalizing the Politico story. But “it wasn’t like Salon was saying we’ve got this scoop,” he noted. “It was a claim without evidence.”

By many names — misinformation, disinformation, rumor — this kind of thing has been a particularly stubborn problem in education.

Many of the fake education stories Snopes knocks down seem to be harmless (if gross) – misbehaving teachers, rumors of free coffee at Dunkin Donuts.

But some of them are quite serious. In January, BuzzFeed noted that the fake Obama ban on the pledge of allegiance being required at schools was the top-shared fake news story of 2016, at 2.7 million shares (a story that I shared unknowingly at the time).

They can impact the public debate over policy issues. Just a few weeks ago, The Grade ran a column about the potential spread of disinformation in education journalism that’s already been documented on hot-button issues like the Common Core academic standards.

And they can divide communities. A recent story in The Guardian described the real-world effects of a fake news story about the supposed ‘Islamic plot’ to take over schools in Birmingham, England.

Education journalists are doubtless aware of the phenomenon of viral fake news in education, but have seemed concerned about it in just a couple of narrow ways: guarding against passing fake news on to readers – the horror! – and writing stories about efforts to educate kids and teachers against disinformation. Their own role in responding to fake news about education issues is something that has not been frequently addressed.

In this, education journalists are not alone. A writeup of a new American Press Institute study finds that U.S. newsrooms are ‘largely unprepared’ to address misinformation online.

Fake news is a problem, but, the thinking seems to have been, it’s someone else’s problem.

The majority of newsrooms only “sometimes” or “very rarely” address misinformation on social media and comment platforms, according to the survey of 59 newsrooms API just published.

Folks concerned about the DeVos rumor spread the alarm on Twitter, tried getting others involved, and pressured Salon and AlterNet to correct their stories.

BuzzFeed education reporter Molly Hensley-Clancy described the Salon story being passed around as “a very shaky 6-day-old Alternet aggregation of Politico’s profile,” noting that the Politico story did not report or even imply that she was going to resign.

Chalkbeat’s Matt Barnum wrote a piece headlined “No, there’s no reason to think DeVos is planning to resign.”

Morning Education, the education newsletter that’s part of Politico, denounced the resignation story: POLITICO did not report DeVos’ days are numbered.

Another education site called The 74 noted that progressive outlets that denounced fake news were now, well, running a fake story.

For his part, Toch tweeted that he hadn’t been “suggesting her plane’s idling at National with a flight plan to Michigan.” (Then he went back into prognostication mode: “I give her a year.”)

Several of the voices heard denouncing the story were far from DeVos allies. “If you’re going to decry ‘fake news’ then you best not be sharing it,” wrote Audrey Watters in her weekly roundup, Hacked Education News.

The collaboration among different journalists and advocates was heartening to some, a silver lining in an otherwise grim situation.

“I saw a lot of other education reporters from many outlets tweeting out the facts here,” said Barnum, understandably appreciative of having been joined by many peers.

Brandon Wright, editorial director for the conservative-leaning Thomas B. Fordham Institute was also gratified that “across the spectrum of the ed policy world, people were very vocal about correcting it, publicly encourage people to not spread such things.”

By Friday, November 10th, Politico’s Morning Education noted that everything was fine: Fake news fixed. AlterNet and Salon had revised their pieces – somewhat.

But of course, while Politico’s honor was somewhat restored, the overall situation was far from fixed.

Politico was among a handful of smaller outlets that attempted to knock down the DeVos resignation rumor.

Conventional wisdom is that viral stories can’t be stopped once they gain steam, no matter how incorrect they may be.

“A lot of the time these things can’t be stopped,” said BuzzFeed reporter Jane Lytvynenko. “I’ll write a debunk of something and it still keeps going. It doesn’t matter no matter how much you refute the disinformation.”

But what if a major news outlet had stepped in to debunk the story. Or what if one of the many fact-checking and anti-disinformation operations that have sprung up in recent years – PolitiFact, Snopes, FactCheck, BuzzFeed, etc. – had gotten involved?

In a case so straightforward as this, without anyone pushing the resignation narrative forward, knocking down the story might have actually worked. The theory is that if someone can catch the story before it’s gone viral, ideally being the first response to a Facebook post or tweet, then it can be blunted. “If you get to it fast enough, you can kill its virality,” said Adams.

But we’ll never know, because that’s not what happened this time.

Distracted, confused, or indifferent, big-reach outlets like the New York Times, AP, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post seemed to have sat on their hands. There was, strangely, nothing from Snopes or PolitiFact or anyone else that I’ve seen.

Education Week, the nonprofit media outlet dedicated to comprehensive coverage of K-12 education issues, seems to have been silent on the issue other than a single tweet from its PoliticsK12 team.

On Monday afternoon, the 13th – a full week after the resignation narrative spread around the internet – the Washington Post’s Valerie Strauss finally found time to get to the story, writing “Don’t bet on her leaving soon.”

But obviously the story was already out there. The damage had been done.

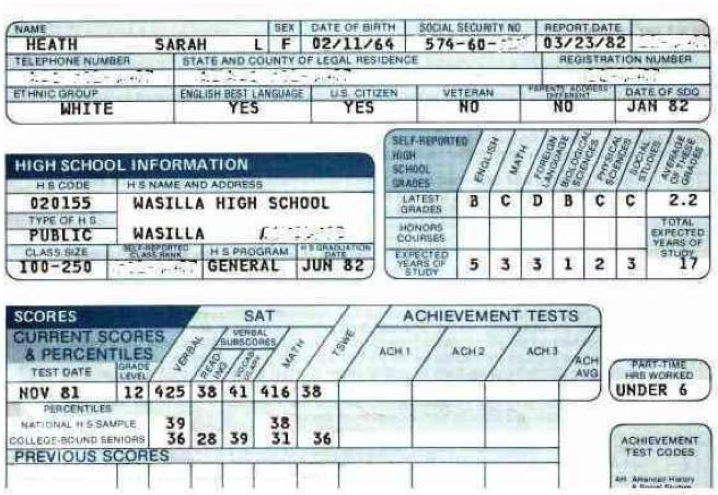

This fake Sarah Palin SAT scoresheet is a good reminder that there’s nothing new about fake news other than its speed of travel.

So, what are the lessons from this DeVos rumor debacle? Here are some tidbits from experts in disinformation and viral news that might help:

YOUR SOCIAL TEAM IS YOUR FRIEND

Lots of outlets have social media and digital engagement staff these days, but there is often a functional and even cultural divide between them and the reporters and editors in the newsroom. Reducing these divides is key to addressing viral disinformation being spread, says Jane Elizabeth, director of the American Press Institute’s Accountability Journalism project.

Better communication among reporters and social media staff can prevent reporters from passing along bad information and – most important in this instance – bring the full weight of a newsroom’s social media infrastructure to bear when a reporter’s personal Twitter account isn’t enough.

“I wonder what would have happened if those education reporters had gone to the social media teams in their newsrooms for help, instead of just trying to take this on themselves using their own accounts,” Elizabeth said in a phone call. “Trying to do this individually is not going to work. They need the power of the main account behind them.”

Some of the reporters involved in the effort to debunk the DeVos rumor may have tried these approaches. As far as I know, institutional accounts from major national news outlets were not deployed.

KNOW YOUR (SOCIAL) BEAT

Reporters tend to know lots about where their colleagues and sources are hanging out on Twitter, and sometimes in real life, and they may use Facebook and Reddit for personal purposes. But they don’t necessarily know where their readers are hanging out online, says Elizabeth – and most don’t know how to use Facebook professionally.

“We all think we know how to use Facebook because we use it in our daily lives, but using it our professional capacity is completely different,” said Elizabeth, who used to write and edit education for the Pittsburgh Post Gazette.

This is a big problem when rumors are being spread and reporters need to be able to target individuals or influencers who might be spreading this or who could stop the spread of this. “You should really be informed about which of Facebook groups on your beat have the most followers and the most active engagement.”

Sometimes, reaching out to the heads of these groups directly can be effective, according to Elizabeth.

A Chrome extension called CrowdTangle seems to be the easiest way to find out how a story is being shared. Plug in the URL for the story you’re wondering about, and the app will tell you the overall numbers (for Facebook, Pinterest, and LinkedIn) and the top-sharing sites (including Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit).

DIY RAPID RESPONSE

There’s a clear and as yet unmet need for a reliable rapid response source for flagging disinformation while it’s still outbound.

“What we try to do is to stop the rumor, we try to break the stream before it spreads too far,” said Snopes’ Brooke Binkowski. Binkowski recommends using old-fashioned email. That didn’t happen in this instance, though she reports that handful of emails were sent to Snopes starting as early as November 2nd.

For now, at least, there is no 24/7 rapid response team, no always-available hotline that can consistently jump in as needed.

In the meantime, be your own rapid response team, both within your outlet and perhaps in collaboration with the teams at other outlets.

WATCH WHO YOU CHOOSE TO QUOTE – AND WHICH QUOTES YOU PICK

The Politico story highlights the importance of reporters finding sources who really know what they’re talking about, limiting the use of unsupported speculation, and being careful not to use the most inflammatory quotes you get just because, well, they’re juicy.

In the Politico story, Alberta quoted critical comments about DeVos from think tank head Tom Toch, even though they were by the reporter’s own admission “somewhat harsher” than what other insiders and USDE staffers had to say.

Based on his quotes, Toch doesn’t appear to have anything to add beyond what any regular reader of education news might know.

In most cases, that’s not a problem. In the current era, there can be enormous repercussions.

Toch declined to be interviewed for this piece. Asked about whether it was wise to have quoted Toch in the way he did, Alberta did not respond.

JOURNALISTS NEED TRAINING, TOO

So far, at least, most of the attention paid to the disinformation issue among education journalists has been focused on coverage of students and teachers being trained to discriminate between fact-based stories and other kinds. The Education Writers Association held some panels about this last spring at their national conference. (See here and here.)

Based on the past couple of weeks, that might need to change.

DEBUNKING IS PART OF THE JOB

It might not seem obvious, but some journalists and news teams don’t think of it as part of their responsibilities to combat disinformation as long as the story is not coming from their own newsroom.

There are all sorts of reasons for this attitude, including a disinclination to take on other journalists’ work and having too many other things going on (pushing out links to their own content being one of them).

But, given the state of the journalism ecosphere right now, and the lack of trust readers have in journalism, it might be time for newsrooms – not just individual reporters – to embrace a broader role that includes addressing false information on their beat.

“It’s our job as journalists to be on the front lines of combating #fakenews on social media,” according to a proposition tweeted from NPR’s Anya Kamenetz.

For the time being, at least, Salon, AlterNet, and other sites prone to passing along misinformation are going to do what they’re going to do, and Facebook and other social platforms are going to keep letting it happen.

The question is whether journalists can take on the role of limiting their impact.

Let’s hope we can be part of the solution next time a story like this comes along.

Related posts:

Hey, education reporter: Can you spot the bot?

Common Core, automated advocacy, & media coverage

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/