The leader of a community school needs specific knowledge, skills, and dispositions to be effective.

And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

What distinguishes community schools from traditional schools? People often point to the various kinds of wraparound services they provide, such as health clinics, food banks, job placement centers, support for struggling families, and so on. Those are the most visible features of the model, so it’s tempting to assume that a community school is nothing more than a regular school plus these extra programs.

In fact, what really defines a community school isn’t the services it provides but, rather, its dedication to involving the whole community in the educational process. At its core, the approach entails a genuine partnership between the school and those it serves.

To build and maintain this sort of partnership requires sophisticated leadership. Anyone can create a health clinic or start a neighborhood tutoring center, but it takes certain kinds of knowledge, skills, and dispositions to infuse those programs with an ethic of mutual respect among teachers, staff members, students, parents, social service providers, and a host of other community members.

Leading a community school takes a special kind of person, one with an entrepreneurial spirit and a strong commitment to equity and social justice.

What do effective community-oriented leaders do to foster such shared beliefs and values? It can be difficult for teachers, staff, and administrators to explain precisely how they’ve managed to create thriving partnerships, but researchers have learned a lot by observing successful community-oriented leaders. For one thing, it has become clear that such leaders build their skill sets and knowledge over time, even if they are unaware that they are doing so. Additionally, leaders’ dispositions — both the traits they were born with and those they’ve cultivated — have much to do with their ability to bring community members together around a common mission.

Leaders can develop the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to create effective community schools, and they should do so purposefully, choosing to learn, model, and practice successful strategies in all aspects of their work. Such leadership is valuable in every kind of school, not just in those that fully embrace the community school approach. As Carlson (2016) found in her analysis of the new professional standards published by the National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA, 2015), an emphasis on community involvement is essential to good leadership at any and all kinds of schools.

Knowledge, skills, and dispositions

Whether they are teachers, counselors, principals, instructional coaches, or play another role in the school, the work of K-12 educators is remarkably complex. As in other established professions, practitioners must use empirical and theoretical knowledge to apply carefully developed skills appropriately to work-related problems (Purinton, 2011), and as they become more seasoned, they come to rely less on formulas and more on improvisational learning, using what is often referred to as “reflection in action” (Schön, 1984, 1987). For teachers of reading, for example, knowledge about phonetics, reading acquisition, the effectiveness of specific instructional strategies, and knowledge of human development (among many other things) must be complemented by skills such as identifying problems in decoding or engaging an entire class in a read-aloud activity.

That’s why the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) — formerly the National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) — calls upon preparation programs to emphasize both knowledge and skills, rather than focusing narrowly on just one of those domains. And yet, the work of educators is even more complicated, requiring not just content knowledge and technical skills but also the capacity to engage and motivate people, listen carefully to them, resolve conflicts, and handle all sorts of nuanced and often delicate interpersonal issues. Thus, CAEP has, over many years, urged preparation programs to focus also on the development of professional dispositions. While teachers or administrators may have all the right knowledge and skills, they cannot succeed in their work unless they also have a well-developed sense of empathy, social justice, fairness, and more.

Here we are concerned with the specific knowledge, skills, and dispositions that leaders need to be successful in building connections among school professionals and members of the community. When emerging school administrators complete their university programs, they likely have a strong knowledge base about school and community leadership. But they need time to learn how to implement the knowledge and skills they learned from books and discussions and to develop the dispositions to make it all crystallize. For example, they may understand the rationale for building a data-driven school improvement plan (and may have participated in doing so as teacher leaders), but it’s something else entirely to bear the full responsibility for that plan’s success, while facilitating important meetings, recruiting new staff, managing competing agendas, and ensuring that key community stakeholders have seats at the table.

Moreover, while the NPBEA standards do not address them directly, soft skills are critically important to the work of building and maintaining strong relationships with community members. Are leaders able to put people at ease and make them feel important, valued, and welcome to contribute? Can they project the warmth and charm to break down barriers and win over skeptics? They have to be willing to humble themselves when necessary and to put aside grudges; they have to look out for the good of the whole but also look out for individuals; they have to be passionate about fairness and social justice; they have to be fully present and available to people who need them, and they have to exemplify these qualities consistently.

In short, to become an effective community-oriented leader, one has to ground oneself in such dispositions, values, and personal commitments, using them to support the implementation of theories, content knowledge, technical skills, and political lessons that make up the majority of content in leadership preparation and coaching programs.

An illustration: Strategic planning

Both NPBEA’s Professional Standards for School Leaders (NPBEA, 2015) and the Coalition for Community Schools’ Community Schools Standards (2017) call on school leaders to develop mission-driven strategic plans that emphasize shared accountability for student success. But if the imperative to cultivate a sense of shared accountability is important in regular schools, it is even more so in community schools.

What makes a community school unique is its distinctly localized and collaborative approach to attaining challenging and ambitious goals. Thus, community-focused leaders must be adept at building cohesion and coalitions within the community around a set of shared ends. But this is no easy task, given that within every community there exist dozens of competing interests and numerous approaches to defining needs, solving problems, and addressing gaps. If community members pull the school in too many directions at once, strategic planning can easily become a chaotic and ineffective process.

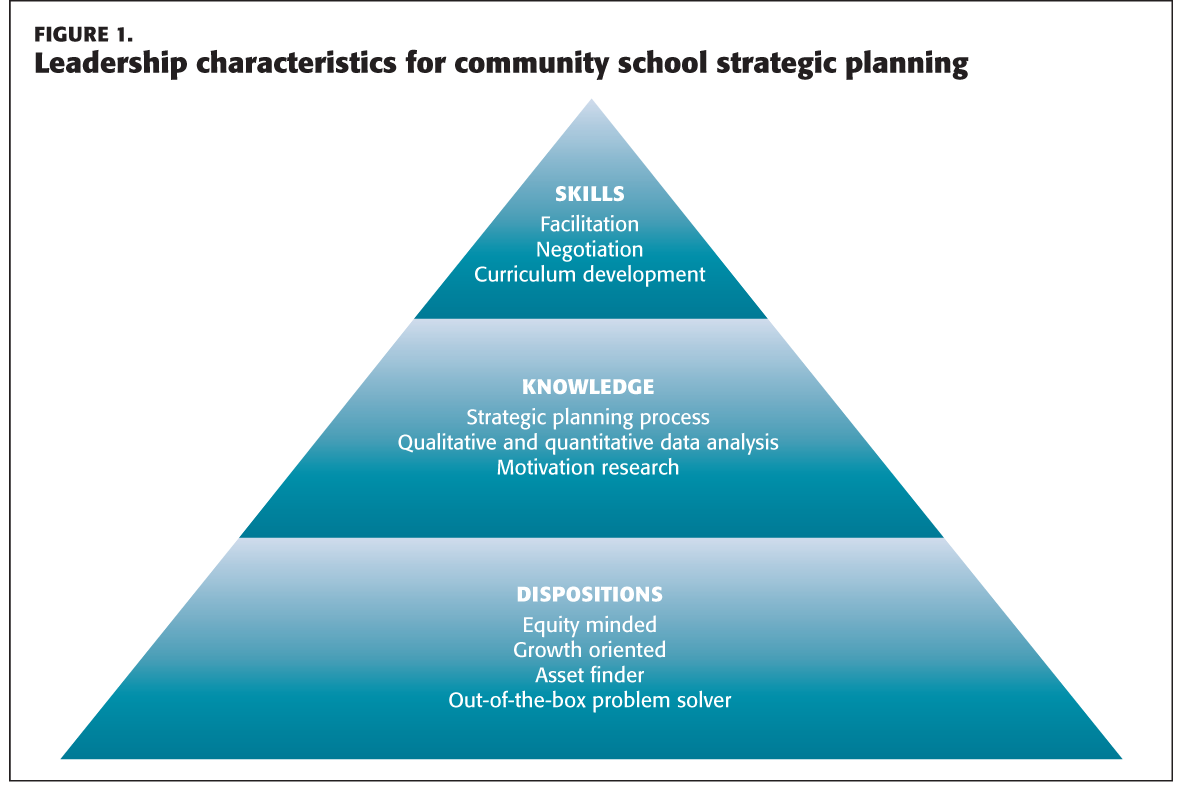

To navigate this complicated terrain, community-oriented leaders need to rely on a stable core of dispositions, such as a strong drive to persevere in the face of challenges, an unshakable dedication to equity, and a commitment to open and honest dialogue. To illustrate how such dispositions connect to the knowledge and skills required to lead community schools, we’ve represented various leadership attributes in pyramid form (See Figure 1). We understand dispositions to be foundational, comprising the base of the pyramid. On the next level are the kinds of knowledge needed, such as a theoretical grasp of the strategic planning process, a technical understanding of quantitative and qualitative data analysis, and a familiarity with research into motivation and engagement. And at the tip of the pyramid — most visible to stakeholders — are the everyday skills (such as facilitation, negotiation, and curriculum development) that leaders use to develop and implement a strategic plan that brings their dispositions and knowledge to life.

Consider negotiation, for example. If a leader has a fundamental disposition toward fairness and equity, and if she has a strong understanding of the strategic planning process in K-12 education, then it will be critical for her to draw upon her skill as a negotiator: She will want to bring various members of the community together to hash out and agree on a plan that they see as fair, equitable, and responsive to their needs and concerns.

Community-focused leaders must be adept at building cohesion and coalitions within the community around a set of shared ends.

The pyramid serves not just to illustrate the connections among leaders’ knowledge, skills, and dispositions but also to help them assess and improve their performance. For example, as part of the process of developing a strategic plan for a community school, the leader will have to facilitate numerous meetings. Using our model, the leader (or her coach) would examine her own facilitation skills by asking questions that focus on each of the three levels:

Skills: Have I done enough to ensure that discussions are inclusive? What can I do to resolve conflicts more effectively and help people arrive at a consensus? How can I balance the need to speak openly about student data with the need to respect confidentiality so that members of the school community can participate fully in reviewing and using the data while ensuring that nobody is embarrassed by that information or feels shut out of the conversation?

Knowledge: What do I know about how to manage and lead effective meetings that use win-win approaches to negotiation? What do I know or what do I need to learn about effective approaches to conflict resolution? What have I learned about this community, its assets, its challenges, and its factions and competing interests?

Dispositions: Do I exhibit a growth mind-set, or am I secretly protective of my turf? What are my biases about members of the community? How will I model honesty and openness even when the interests of various community members complicate the strategic planning process?

We’ve found it useful to guide leaders through this kind of three-part assessment to review and improve their performance in any number of areas critical to community schooling: instructional leadership, partnership development, resource management, safety and security, and so on. By examining their own skills, knowledge, and dispositions, leaders often discover hidden strengths and identify target areas for growth, allowing them to define much more tangible and effective strategic plans.

What is invisible to the eye

Leading a community school takes a special kind of person, one with an entrepreneurial spirit and a strong commitment to equity and social justice. Yet, we have seen in hundreds, if not thousands, of cases over our collective careers that good leaders are not just born — they can be developed. By weaving the threads of knowledge, skills, and dispositions into a leadership tapestry focused on meeting high standards, leaders can transform their schools and communities. When the entire school community participates in the life of a school, positive perceptions grow, and the educational agenda becomes stronger. Community-oriented leaders develop alliances and partnerships as coproducers of a movement in which all parties work, plan, dream, and celebrate together.

References

Carlson, K. (2016). Preparing aspiring leaders for community school leadership. In T. Purinton & C. Azcoitia (Eds.), Creating engagement between schools and their communities: Lessons from educational leaders. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Coalition for Community Schools. (2017). Community schools standards. Washington, DC: Institute for Educational Leadership.

National Policy Board for Education Administration (NPBEA). (2015). Professional standards for school leaders. Washington, DC: Author.

Purinton, T. (2011). Six degrees of school improvement: Empowering a new profession of teaching. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Purinton, T. & Azcoitia, C. (Eds.). (2016). Creating engagement between schools and their communities: Lessons from educational leaders. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Schön, D. (1984). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Originally published in February 2018 Phi Delta Kappan 99 (5), 39-42. © 2018 Phi Delta Kappa International. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Ted Purinton

TED PURINTON is dean of the Bahrain Teachers College, University of Bahrain, Manama, Bahrain.

Carlos Azcoitia

CARLOS AZCOITIA is distinguished professor of practice in educational leadership, National Louis University and former principal of Spry Community Links School, both in Chicago, Ill.

Karen Carlson

KAREN CARLSON is retired chair for educational leadership programs, Dominican University, River Forest, Ill., and a former superintendent and principal of two community schools.