Too often, school dress codes are enforced in ways that disproportionately impact students of color — both male and female.

“I am aware of what makes me feel uncomfortable. If what I wear bothers someone else, it says more about them than me.”

— Tyra, a multiracial female student

“When you have a Black girl and a White girl walking down the hall, and the Black girl gets called out, I mean, that’s the issue.”

— Emma, a White female teacher

Dress codes have always been a point of contention in public schools. Teachers, students, parents, and administrators struggle, often against each other, to determine what is appropriate for school and who should get to decide. Recent headlines in the popular press highlight stories of girls and young women who were forced to wear a sweatshirt over a tank top during a heat wave, put tape over their nipples if they were not wearing a bra, or remove hair extensions. In the era of Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, these news stories highlight ways that seemingly neutral school policies may inequitably impact students based on their gender and race.

When students are disciplined because of how they are dressed, they lose class time — for a five-minute hallway lecture, 20 minutes to search through a bin of “appropriate” clothes to wear, an hour-long trip home, or even a full-day suspension. Perhaps even worse than losing out on instructional time, they also receive the message — whether explicit or implicit — that there is something wrong with their clothing choices or their bodies. Such messages create unwelcome and potentially even hostile school climates for students whose choice of dress goes against established norms. And students are taking notice and speaking out. A group of New Jersey students, for example, created the hashtag #Iamnotadistraction to push against dress codes that required female students to cover their bodies, implicitly blaming them for distracting males from learning (Krischer, 2018).

Despite this growing attention, schools continue to enforce dress codes that are explicitly gendered and implicitly aimed at minority cultural groups. The National Women’s Law Center (2018) recently reported that although many dress codes in the Washington, D.C., area included race-neutral language, they specifically banned styles mostly worn by Black girls and women, such as hair wraps. While research on school discipline and its disproportionate impact on Black males has abounded (e.g., Fergus, 2016), the research on racialized effects of dress codes is still emerging. To further investigate this phenomenon, we looked at one high school’s dress code and its differential impact on students.

A dress code in action

Lincoln High School (a pseudonym) serves 1,200 students in a small Midwestern urban community. Lincoln’s student body is about 40% White, 35% Black, 10% Latino, and 10% multiracial; about two-thirds of the students are classified as economically disadvantaged.

In response to school and community members’ concerns about racial inequities in the local schools, a Social Justice Task Force was formed to investigate the problem and develop strategies to address it. This included trainings for all school employees at which they discussed issues at their schools where race may be a factor, implicitly or explicitly. When a task force member informally asked students what issues fit this description, their immediate response was, “The dress code!”

A different type of dress code is needed that helps schools and students to challenge dominant narratives of who they are or could be.

To better understand the students’ concern, we surveyed all Lincoln High School students (receiving 384 responses) and randomly sampled 13 teachers to interview. The survey asked students about the frequency with which they followed the dress code, the degree to which they were disciplined about their dress, and their opinions about the dress code more generally. Teacher interviews focused on their beliefs about the dress code, in general, and in relation to race and gender. Ultimately, we hoped to answer the question: To what degree, if at all, does Lincoln High School’s dress code disproportionately affect students based on their gender and/or race?

Disproportionate enforcement by race and gender

Lincoln’s dress code forbids clothing that administrators deem too revealing, with specific bans on spaghetti straps and tube tops, visible midriffs or cleavage, and dresses, skirts, and shorts that do not extend past the middle knuckle when arms are straight down. Undergarments (including bra straps) should not be visible, and leggings are prohibited. Head coverings that are not for religious purposes are also not allowed.

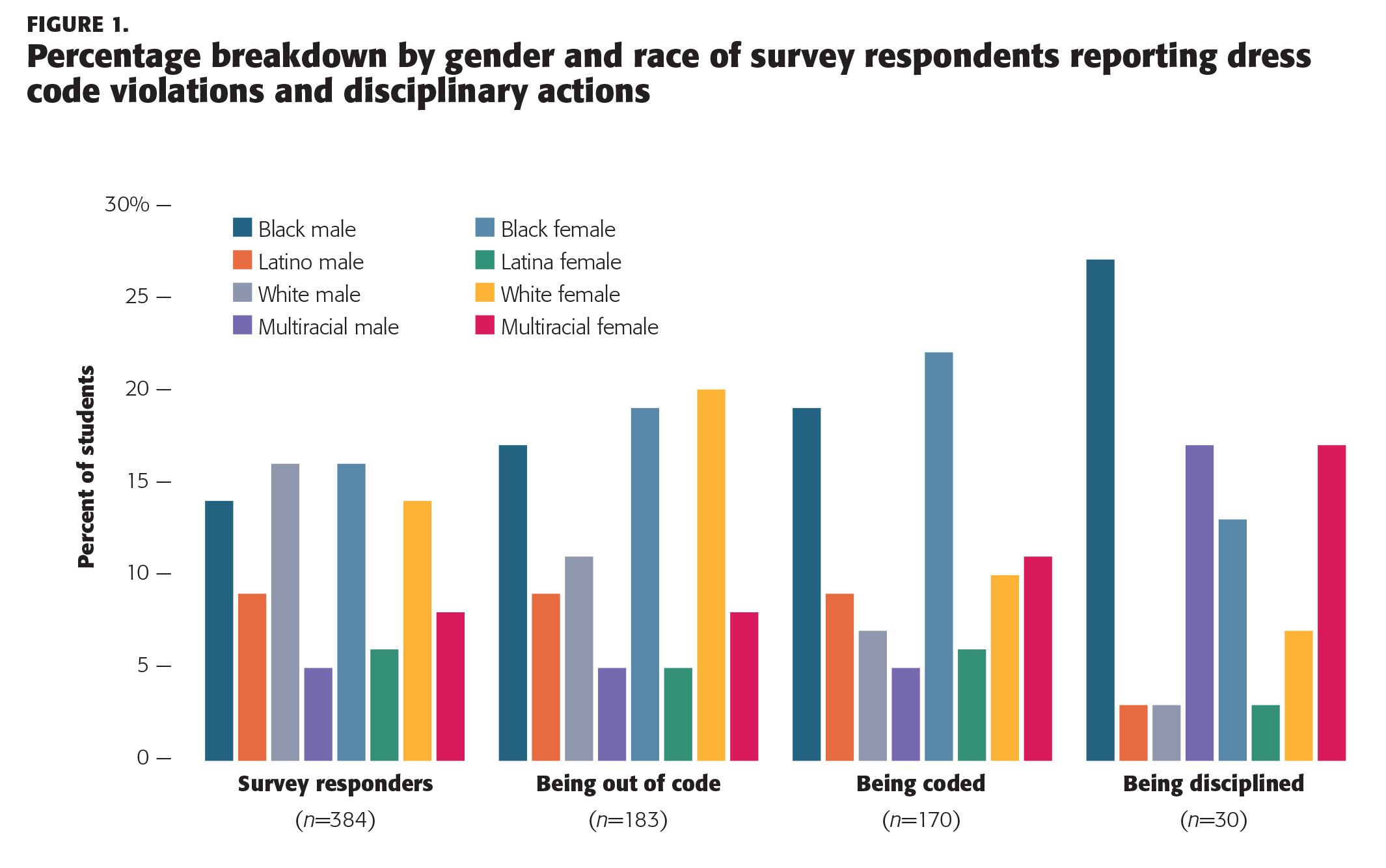

In most cases, students reported similar frequencies of dress code infractions, with White females and Black males reporting slightly higher rates and White males slightly lower rates. This would lead one to expect that dress code infractions would line up with their representation within the school. However, when we look at the likelihood of students being “coded” (i.e., having a school adult ask them to remove or cover a clothing item), we see a different picture (see Figure 1). Black males, Black females, and multiracial females stand out as students who reported being disproportionately coded. On the other hand, White females and White males were much less likely to report being coded. Essentially, survey responses showed that students of color are more likely to be coded for breaking the dress code even if they do so at a similar rate to White students. The disproportionality is even more striking when looking at which students report being disciplined, which may involve a suspension, detention, or being sent home. While only 30 of the 384 survey participants reported being disciplined, they were overwhelmingly Black and multiracial, male and female.

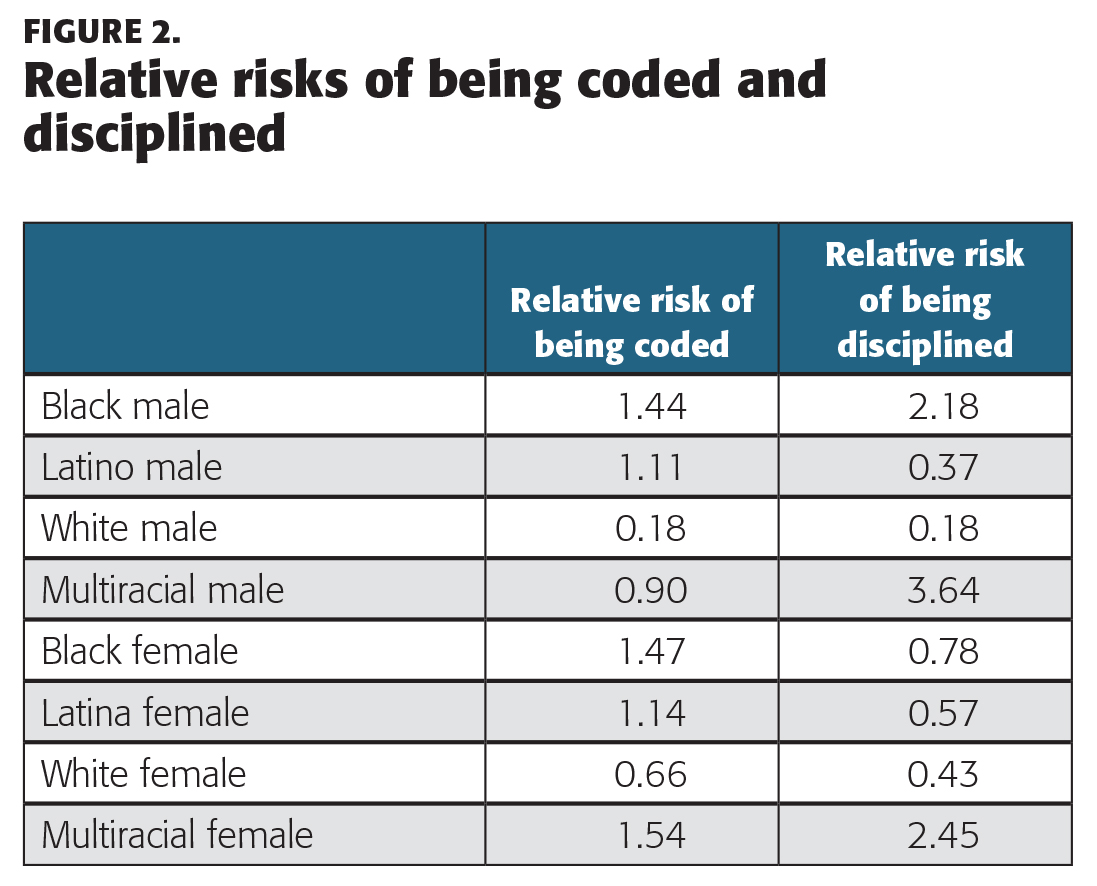

Another way to look at these data is through the concept of relative risk, or the probability of an event occurring for one subgroup in comparison to that of the group at large. A relative risk score of 1.0 means that there is no difference in terms of the probability of the event occurring to an individual in the subgroup versus in the group at large. Looking at the data through this lens clearly shows that Black males and females and multiracial females report a greater risk of being coded and that Black and multiracial males and multiracial females report a greater risk of being disciplined (see Figure 2).

Looking at Lincoln High School’s dress code from the perspectives of students and teachers, it quickly becomes clear that racial and gender narratives are at play in students’ experiences of the dress code. Students’ and teachers’ perspectives illustrate two narratives about how students of color are affected differently by the seemingly neutral policy. For males of color, the dress code and the ways it is enforced are related to the larger U.S. narrative that criminalizes them. On the other hand, females of color are sexualized by the dress code and blamed for creating a negative school climate.

Criminalization of males of color

Students and teachers of all genders and racial/ethnic backgrounds reported that males of color were most likely to be coded, even if White males had similar dress code infractions. Several males of color said they believed the school was positioning them as criminals or potential criminals. One Black male student thought the rule against hoods was because teachers and administrators were worried that students might “have a weapon in our hoods.” Another male of color, who liked to wear a do-rag to school, said he was always told to “take it off ’cause the cameras can’t recognize me.” He wondered how a do-rag could prevent security personnel from recognizing him when the head covering “doesn’t even cover nothing but my haircut.”

The dress code as enforced treated males of color as potential threats who needed to be watched over and disciplined.

Teachers said that there was a need to be able to identify students from the cameras or from a distance, with one sharing an example of a time when a few individuals (not enrolled students) entered the school to start a fight with students. Students, however, found that the targeting of males of color for the head covering rule weakened this argument. If only males of color are coded, while White males wear hats or hoods without comment, then it is clear, to them, that the rule is not about safety and that the issue is not about consistency of enforcement. Rather, the dress code as enforced treated males of color as potential threats who needed to be watched over and disciplined.

Sexualization and blame of females of color

Female students consistently reported that the dress code sexualized them, treating common U.S. clothing options, such as a spaghetti strap tank top, as though they were revealing, alluring outfits that distracted male students from learning. Samantha Parsons (2017), who developed a dress code advocacy guide based on her experiences advocating for a gender-neutral policy in her own community, found that dress codes across the country promote narratives of females as objects and potential victims of harassment, assault, and rape because of their clothing choices (and not the actions of their perpetrators).

Lincoln’s female students believed that they were coded more often partly because of the number of specific rules related to clothing items traditionally worn by young women in the United States, such as skirts and certain styles of shirts. The large number of rules about what they wear, however, did not mean that females of all races were similarly affected, as females of color, especially those who were Black or multiracial, were disproportionately represented in reports of being coded and formally disciplined. When females of color, breaking the dress code at similar rates to White students, get coded more often, it suggests that teachers and administrators see their clothing as too “revealing,” while White female clothing is acceptable. In other words, females of color may be seen as sexual and thus a problem, where White females are not. This experience of females of color presents an example of what Kimberlé Crenshaw has called intersectionality, a way to understand how racism and sexism interact. According to Crenshaw (1989), the “intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism” (p. 140) because racism and sexism are compounded, creating a system of structural oppressions whose effects are particularly intense for women of color.

By insisting that female bodies are the problem, and focusing specifically on female bodies of color, the school perpetuates the mentality that their bodies are primarily sexual.

Body type may also be a factor in who is disciplined for dress code violations. One teacher noted, “Dresses are a little touch and go because of girls’ shapes. Typically if you are much smaller, it doesn’t look as risqué.” In other words, two girls could be wearing the same exact piece of clothing, but depending on their body type, one would be out of dress code — and in most cases, those being identified as out of dress code, according to students and teachers, were females of color.

One teacher reflected on this, sharing that he does not code female students because, “If I ask a girl to change . . . I am afraid of the perception that will put on me as a male teacher. I don’t want to be accused of being a pervert.” However, this teacher may be an outlier, as overall the teachers and administrators at Lincoln High School did not express concerns about sexualizing females of color. Yet by insisting that female bodies are the problem, and focusing specifically on female bodies of color, the school perpetuates the mentality that their bodies are primarily sexual.

Moving forward

While several teachers acknowledged concerns about the dress code, some continued to believe the primary issue was not about race, gender, or their intersections, but an issue of inconsistent enforcement. This belief seems to be prevalent across the United States, as Lincoln High School’s dress code is pretty typical. However, Lincoln’s students, and students across the country, recognize that the inconsistency is not a result of random chance but of teachers and administrators’ beliefs about children — that boys of color are potential criminals and that girls of color are sexual beings. Instead of tinkering with specific rules or training teachers to enforce this dress code better, a different type of dress code is needed that helps schools and students to challenge dominant narratives of who they are or could be.

This work is already underway in several districts across the country, including San José Unified School District (SJUSD) in California and Portland Public Schools (PPS) in Oregon. SJUSD administrators are addressing the ways school dress codes sexualize female students by eliminating gender-specific language in their schools’ dress codes. Instead of calling out specific garments typically worn by girls, such as spaghetti straps or tube tops, SJUSD’s new dress code (2018) states that “Clothing must cover the chest, torso, and lower extremities.” In addition, the district’s written policy begins with the statement that “the responsibility for the dress and grooming of a student rests primarily with the student and his or her parents or guardians and that appropriate dress and grooming contribute to a productive learning environment.” And, importantly, the policy recognizes that asking students to change their clothes takes away from learning time, and it asks administrators to be attentive to how their decisions negatively impact students’ educational opportunities.

Portland Public Schools, meanwhile, has taken steps to allow head coverings while also making it possible for security personnel to easily identify students. Their dress code states, “Hats and other headwear must allow the face to be visible and not interfere with the line of sight to any student or staff. Hoodies must allow the student face and ears to be visible to staff” (PPS, 2018). This type of rule allows males of color to wear do-rags or baseball caps, which many students at Lincoln High School preferred to do to cover up their hair, while still enabling school personnel to easily identify them.

Any adoption of a dress code must involve open discussions about how different individuals interpret subjective concepts such as “professional,” “distracting,” and “good taste.” Adults need to be aware of their beliefs about children and young adults and how their beliefs influence their practice: Which students do they call out? Whom do they see as criminals? Whom do they see as distracting? Which infractions do they choose to not see? If a school community fails to ask these questions, female and male students of color will most likely continue to be sexualized or criminalized at the expense of their education.

References

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989 (1), 139-167.

Fergus, E. (2016). Solving disproportionality and achieving equity: A leader’s guide to using data to change hearts and minds. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Krischer, H. (2018, April 17). Is your body appropriate to wear to school? New York Times.

National Women’s Law Center. (2018). Dress coded: Black girls, bodies, and bias in D.C. schools. Washington, DC: Author

Parsons, S. (2017). Not a distraction: An advocacy guide for policy change around school dress code. n.p.: Author. http://bit.ly/ParsonsNotaDistraction

Portland Public Schools. (2018). District dress code policy. Portland, OR: Jackson Middle School.

San José Unified School District. (2018). San José Unified Student Handbook. San José, CA: Author.

Citation: Pavlakis, A. & Roegman, R. (2018) How dress codes criminalize males and sexualize females of color. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (2), 54-58.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Alyssa Pavlakis

ALYSSA PAVLAKIS is a master’s student in education at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Rachel Roegman

RACHEL ROEGMAN is an assistant professor in the Department of Education Policy, Organization, and Leadership at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.