A carefully planned sex education curriculum can help young people navigate thorny questions responsibly and with confidence.

Should schools be teaching sex education? Opponents say leave it to parents, but few mothers and fathers do a good job preparing their children for the sexual challenges of adolescence, let alone for caring, ethical, and fulfilling sex lives as adults. The reasons are pretty straightforward: Parents aren’t trained sex educators, they often have difficulty accepting that their tweens and teens are sexual beings, and those tweens and teens tend to be intensely uncomfortable talking about this stuff with Mom and Dad. Parents do the best they can, but their kids need much more.

Why? Because in addition to managing their own hormonally driven desires, young adolescents’ brains are inundated with sexual stimuli from all sides:

- Provocative content in movies, TV shows, and advertisements;

- Readily available Internet pornography, serving as “sex education” for many;

- Social media rife with flirtation and sexting;

- Peers confidently spouting misinformation;

- Pressure for casual sex as part of the (much-exaggerated) “hookup culture”;

- Everyday sexual harassment of up to 84% of young women (Schwiegershausen, 2015);

- Sexual abuse experienced by 1 in 5 girls and 1 in 20 boys by age 18 (Finkelhor, 2009).

Who will guide teenagers through the sexual wilderness? A 2017 PLOS poll found that 78% of U.S. parents (across the political spectrum) were fine with outsourcing sex education to schools (Kantor & Levitz, 2017). But if educators are going to be the ones teaching sex ed, they need to get it right, and their track record is not encouraging. Teacher training and support are uneven, few schools go beyond the basics, and there’s timidity on the very subjects young people need to think through carefully (see Orenstein, 2016, for a thorough critique).

Dealing with sexual desire is one of teens’ most challenging tasks.

In my 25 years teaching sex ed to 5th and 6th graders, I’ve learned that effective sex education depends on making good decisions in these seven areas: when to teach it, what content to include, what pedagogical approaches to use, how to assess learning, how to involve parents, what ground rules to set, and whether to separate boys and girls.

What is the best age?

Given the earlier onset of puberty among American youth (mostly the result of better nutrition over the last 100 years) and the startlingly young age at which kids are exposed to sexual content, many schools now begin sex education in 5th grade. The rationale is that students need to understand what’s happening to their bodies, learn the basics of sexuality and reproduction, and pick up some refusal skills in preparation for sexual shenanigans in middle school. But some parents and educators believe 5th grade is too young. In fact, every time I taught a class of 5th graders, two or three parents opted their children out, and for those who did get permission, some of the content was over their heads.

So what is the best age? One solution is to phase in the curriculum from kindergarten through high school, introducing new and developmentally appropriate topics each year. This sounds logical, and some curriculum packages do a thoughtful job spreading the material across K-12. (See, for example, the Our Whole Lives curriculum from the Unitarian Universalist Association.) In general, though, it’s challenging to ensure high-quality instruction at so many grade levels, and there’s a strong possibility that these uncoordinated pieces will leave students unprepared to make good decisions in their teen years (when the consequences of unwise choices become quite serious).

A better approach, I would argue, is to address sexual abuse prevention in 2nd or 3rd grade and then teach more comprehensive sex ed courses in 6th grade (when more students are ready for it) and 9th grade (right in the middle of many adolescents’ sexual decision-making). This 1-2-3 punch allows schools to focus training and curriculum development at three strategic points and carve out the time needed to do justice to the subject matter.

What’s the purpose and content?

As Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe (2008) have argued, effective course planning often starts from the “big ideas” students should grasp by the end of a course, then moves backwards to the beginning. Starting with the end goals in mind helps instructors identify likely misconceptions, frame essential questions, and decide on the best pedagogy.

The big ideas that shaped my sex ed courses included:

- Sex is normal. It’s a deep, powerful instinct at the core of our survival as a species. Sexual desire is a healthy drive, and having a good sex life (quite apart from procreation) is an important part of adult happiness and self-esteem.

- Sex can harm people. Sadly, it’s sometimes one-sided, exploitative, traumatizing, even life-threatening. A surprising number of people have had bad experiences with sex, including harassment, abuse, rape, and contracting sexually transmitted diseases, all of which can do lifelong damage.

- Many people have difficulty talking about sex. Euphemisms, slang, and jokes are common when people are misinformed, awkward, embarrassed, or ashamed.

- Adolescence is tricky. Twenty-first-century Americans reach puberty almost 10 years before society considers it acceptable to have intercourse. Teenagers have strong sexual urges and are bombarded with cultural messages (Just do it!). Dealing with sexual desire is one of teens’ most challenging tasks.

- Early sex is risky. Two characteristics of adolescence are a sense of invulnerability and underdeveloped executive function. These result in many teens becoming sexually active without thinking through short- and long-term consequences.

- Values matter. Some areas are controversial, like premarital sex and abortion, but there’s almost universal agreement on the following values: Sexual exploitation of children is wrong. Sex should always be consensual. Knowledge and open communication are good, ignorance and dishonesty are bad. Sex is best in a relationship that combines passion, intimacy, and commitment. Marriage is a strong institution in which to raise children.

- Assertiveness is an important life skill. Many young people will be tempted, pressured, or forced to have sex that is harmful. Knowing how to avoid and/or deal with such situations is crucial.

These big ideas helped me frame the twelve lessons of my course for 5th and 6th graders (a 9th-grade curriculum would be somewhat different):

- Lesson 1: Overview, ground rules, and a pre-test

- Lesson 2: Male puberty — physical and emotional changes

- Lesson 3: Female puberty — physical and emotional changes

- Lesson 4: Male-female similarities and differences; the issue of masturbation

- Lesson 5: Sexual intercourse, pregnancy, and childbirth

- Lesson 6: Sex at its best — falling in love, the nature of true love, marriage

- Lesson 7: Facts, attitudes, and myths about LGBTQ+ issues and identities

- Lesson 8: Birth control and abortion

- Lesson 9: Sexually transmitted infections

- Lesson 10: Sex without love — harassment, sexual abuse, and rape

- Lesson 11: Being assertive — dealing with pressures and deciding on values

- Lesson 12: Wrap-up, post-test, and an application task

Two of the most important big ideas — becoming more comfortable talking about sex and being able to apply knowledge to real-life situations — were integrated throughout the course rather than being the central focus of a specific lesson.

What about pedagogy?

The first step to effective instruction is choosing the right teachers. An ideal configuration is to have male and female co-teachers modeling comfortable rapport on all topics, but that’s not always possible. More important is that teachers are mature, comfortable talking about sex, and supportive of the goals of the course. Teachers should also have good classroom management skills; avoid overreacting when students giggle in early lessons; teach students to use correct vocabulary and wean them from profanity; have a sense of humor but not allow inappropriate humor and quickly shut down teasing and ridicule; prepare thoroughly for each class but nimbly respond to unexpected questions; be confident and authoritative, while admitting gaps in knowledge; be authentic but not share personal sexual experiences; encourage student participation but not let students overshare, and avoid using unapproved materials and guest speakers.

In terms of classroom management, I believe sex ed calls for more structured, teacher-centered approach than teachers might use in other subject areas. That’s because the potential for teasing and inappropriate comments is very high when young people are exposed to sexual content in less-structured formats like turn-and-talk and open-ended discussions. There’s also the challenge of sex education teachers being the sole center of attention as they present material that is unfamiliar and emotionally charged. I’ve found that using PowerPoint slides is helpful for the following reasons: when everyone is looking together at what’s on the screen, the focus is on the content, not the teacher; well-sequenced and illustrated slides serve as cue cards for the teacher, making for heads-up teaching (no need to look at notes); and slides can display diagrams and photographs for group discussion, saving the expense of copying or purchasing print materials.

A helpful pedagogical move is to kick off a sex education course with a set of provocative, open-ended essential questions (mirroring the big ideas) that recur naturally from lesson to lesson. Some suggestions:

- Why was sex invented?

- How can sex, which is supposed to be wonderful, hurt people?

- Why are there so many swear words, jokes, and lies about sex?

- How can kids deal with having sexual urges way before they’re supposed to have sex?

- When is it OK for a person to have sex with another person?

- What’s love got to do with it?

- With sex, what’s normal and what’s not, what’s right and what’s wrong?

- Are bad sexual experiences inevitable and irreparable?

At the end of a successful course, students should be able to give thoughtful answers to all the essential questions.

In my own course, I found it helpful to start each lesson by sharing three or four newspaper advice column questions on the topic of the day (for example, male puberty), not answering them up front, and telling students that at the end of the class I would ask for volunteers to answer each one. There were always a few students willing to do this, and if their “advice” wasn’t complete, I’d ask others to chime in. This gave students practice using correct terminology, speaking appropriately about sex in front of their peers, and applying what they’d just learned to a real-life situation.

Another helpful technique was to give students a one-page summary of the day’s information at the end of each lesson and having students collect these sheets in a folder. On the last day of the course, students took their folders home, along with copies of their assessments, providing material for family discussions and future reference.

What’s the best way to assess learning in sex ed ?

I recommend bookending a sex ed course with a detailed assessment that’s given as a pre-test in the first lesson and a post-test in the last. (Examples of the pre- and post-test I use are available at https://marshallmemo.com/marshall-publications.php)

I usually administer the pre-test by reading the questions aloud and having students write their answers. This is helpful because: (a) it makes the test a shared rather than an individual experience; (b) it supports students who are unfamiliar with some of the vocabulary or read at a lower level; (c) it helps desensitize students to sex vocabulary that initially makes them uncomfortable; (d) it gives students a road map to the curriculum, piques their curiosity, and highlights important concepts and misconceptions; (e) it brings overconfident students down a notch as they realize they have a lot to learn; (f) it gives teachers the opportunity to reassure students that it’s just a pre-test and encourage them to set a goal for the post-test, and (g) it allows teachers do an item analysis and highlight topics that need special attention.

My favorite method of checking for understanding during lessons is to use “clickers” (wireless audience response devices) or cell phones and tablets with software like Kahoot or Socrative. These technologies make it possible to ask questions, immediately display students’ anonymous responses, and clarify if there’s confusion.

For the post-test, students are usually focused and eager to show their mastery, and there are big gains in knowledge from the pre-test. However, no multiple-choice, fill-in-the-diagram test can assess deeper levels of understanding and application. That’s why it’s important to have an application or performance task. In my course, I posed the following scenario right after students completed the post-test: Your 14-year-old cousin in another city says she’s in love with a 17-year-old boy and believes they are ready to have sex. She asks for your advice. This task measures whether students can apply what they’ve learned in an all-too-realistic situation, understanding the emotions of the kids involved and thinking about how to present key information in a persuasive way. My students took this task very seriously and drew on the entire course as they wrote their letters, which I scored on a 4-3-2-1 rubric. Nobody ever said, Just do it!

How should parent information be handled?

It’s important, politically and ethically, to get explicit parent permission for sex education; indeed, state law may make that mandatory. Parents are their children’s first and most important sex educators, especially in the area of values and behavioral expectations, and they need to know in advance what’s being taught, feel confident about the teacher, and be able to opt out with no stigma for their children. Some schools use “negative permission” letters (If we don’t hear from you, we’ll assume you consent), but I advise against this approach because messages can be lost or waylaid. The last things schools need is angry parents who’ve just discovered their child is in a sex ed course they never heard about. A permission letter should contain the basic rationale for the course, an outline of the curriculum, teachers’qualifications, and an option to get more-detailed information and perhaps attend an evening Q&A session.

If students are nervous about a sex ed course (Won’t I be embarrassed? Can teachers control teasing and rude remarks?), they may try to persuade their parents not to give permission. When I first taught sex ed, I hit upon a strategy for countering this tendency and maximizing student attendance. A week before the course, I visited each class and answered questions before handing out the permission letter. Students asked questions like, Why are we doing sex ed? Isn’t that our parents’ job? I know all about sex; isn’t this a waste of time? What if I ask a question and everyone laughs? Will you separate boys and girls? Will you call on me if I don’t raise my hand? Will I get a sex ed grade on my report card?

When answering these and other questions, I tried to model the matter-of-fact, unruffled demeanor I’d maintain throughout the course. I also told students that on the first day of class, I would give a comprehensive pre-test, and any student who got 100% would get 10 dollars. This created great excitement, and there were always students who were sure they would win the prize. At the end of these 20-minute introductory talks, students were reassured and excited, and most went home and lobbied for permission. (In all the years I taught sex education, there was only one student who walked out with ten dollars: She was repeating fifth grade, studied her copy of the test from the previous year, and aced the test.)

What ground rules are appropriate?

A top priority is to make clear up-front that sex ed is different from math or social studies. I suggest posting ground rules on the first day and having a clear procedure for removing disruptive students. Some suggested rules:

- No teasing, put-downs, or harassment. Students need to be very clear that such behavior, inside or outside the class, will be dealt with very strictly.

- No personal questions. Students might practice saying, “That’s a personal question and I’m not going to answer it.”

- No such thing as a stupid question. Students shouldn’t be afraid to ask anything, perhaps anonymously on index cards.

- Respect diverse opinions. Students need to listen to and not condemn views with which they strongly disagree.

- Discuss sex only at appropriate times and places. This is probably not a topic for Thanksgiving dinner with Grandma at the table.

- Stick to the topic. A well-organized sex ed lesson is crammed with information, and it’s impossible to do justice to the topic of the day while answering questions on other subjects.

- No cold-calling. Students can be completely silent throughout the course if they wish.

Should boys and girls be taught together?

Over the years, many schools have taught sex ed in single-gender classes, often with different content — for example, girls learning about menstruation and boys about wet dreams. Even if boys and girls have the same curriculum, some educators believe that students (especially girls) are more likely to open up and ask questions in single-gender classes.

I disagree. Just before a sex ed course, some apprehensive students may request single-gender classes, but once they see that teachers are comfortable with the subject matter and won’t tolerate teasing and harassment, they usually change their minds. Most kids are fascinated with all the stuff they don’t know about the opposite sex and want to learn about it together.

In addition, consider the message young people hear when boys and girls are separated: This subject is so sensitive that we have to build a wall between the sexes when we talk about it. The reality is that most students live in mixed-gender families and are very likely to date people of the opposite sex. Single-sex classes don’t give students the opportunity to see models of comfortable male-female communication and to practice such discourse themselves. If kids are flustered and tongue-tied talking about sex, they’re more likely to make poorly informed choices later on. An additional argument against single-gender classes: Where do teachers place students who identify as nonbinary?

If kids are flustered and tongue-tied talking about sex, they’re more likely to make poorly informed choices later on.

My recommendation is to hold firm on coed classes, ensure that teachers have the right skills, and tell students that after the first couple of classes, those who still feel they can’t learn with the opposite sex can opt out. If educators or parents won’t accept this approach, a compromise is to offer gender-separate classes on the most sensitive topics. If even that won’t fly and the battle isn’t worth fighting, boys and girls might be taught separately, but all classes should get the full curriculum.

A worthy gift

A well-formulated, well-taught sex education course makes a tremendously important contribution to young adolescents’ development. It will help them sort out the confusing messages they get from peers, social media, TV, movies, and the internet; talk comfortably and knowledgeably about sex with family members, friends, and lovers; and greatly improve their chances of making it through the teen years without disturbing or traumatizing sexual experiences. Good sex education might even help them lead happy sex lives as adults. These are worthy goals!

References

Finkelhor, D. (2009). The prevention of childhood sexual abuse. Durham, NH: Crimes Against Children Research Center. www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/CV192.pdf

Kantor L. & Levitz N. (2017). Parents’ views on sex education in schools: How much do Democrats and Republicans agree? PLoS ONE, 12 (7): e0180250.

Orenstein, P. (2016). Girls and sex: Navigating the complicated new landscape. New York, NY: Harper.

Schwiegershausen, E. (2015, May 28). The Cut. www.thecut.com/2015/05/most-women-are-catcalled-before-they-turn-17.html

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2008). Understanding by design. Alexandra, VA: ASCD.

Sex education resources

- Kim Marshall’s sex education pre- and post-test, summaries of lessons, and other resources. Information on Marshall’s curriculum, being piloted in 25 middle schools, is available upon request.

- It’s Perfectly Normal: A Book About Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex, and Sexual Health by Robie Harris, illustrated by Michael Emberley (Candlewick, 2009). A superb book geared to early adolescents, tastefully and humorously illustrated.

- The Talk: How Adults Can Promote Young People’s Healthy Relationships and Prevent Misogyny and Sexual Harassment. A report by Richard Weissbourd, with Trisha Ross Anderson, Alison Cashin, and Joe McIntyre for Making Caring Common. The website includes tips, a resource list, and other resources for parents and educators.

- National Sexuality Education Standards: Guidance on the essential minimum, core content that is developmentally and age-appropriate for students in grades K–12.

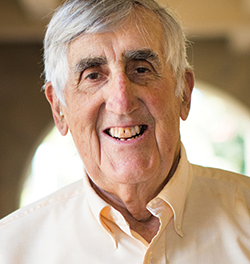

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kim Marshall

Kim Marshall, formerly a Boston teacher and administrator, now coaches principals, consults, and speaks on school leadership and evaluation, and publishes the weekly Marshall Memo. He is the author of Rethinking Teacher Supervision and Evaluation (3rd ed., Jossey-Bass, August 2024).

Visit their website at: www.marshallmemo.com