Schools must connect the strands across dozens of teachers, thousands of lessons, and 15,000 hours of schooling to ensure that each students leaves as a well-educated, decent human being.

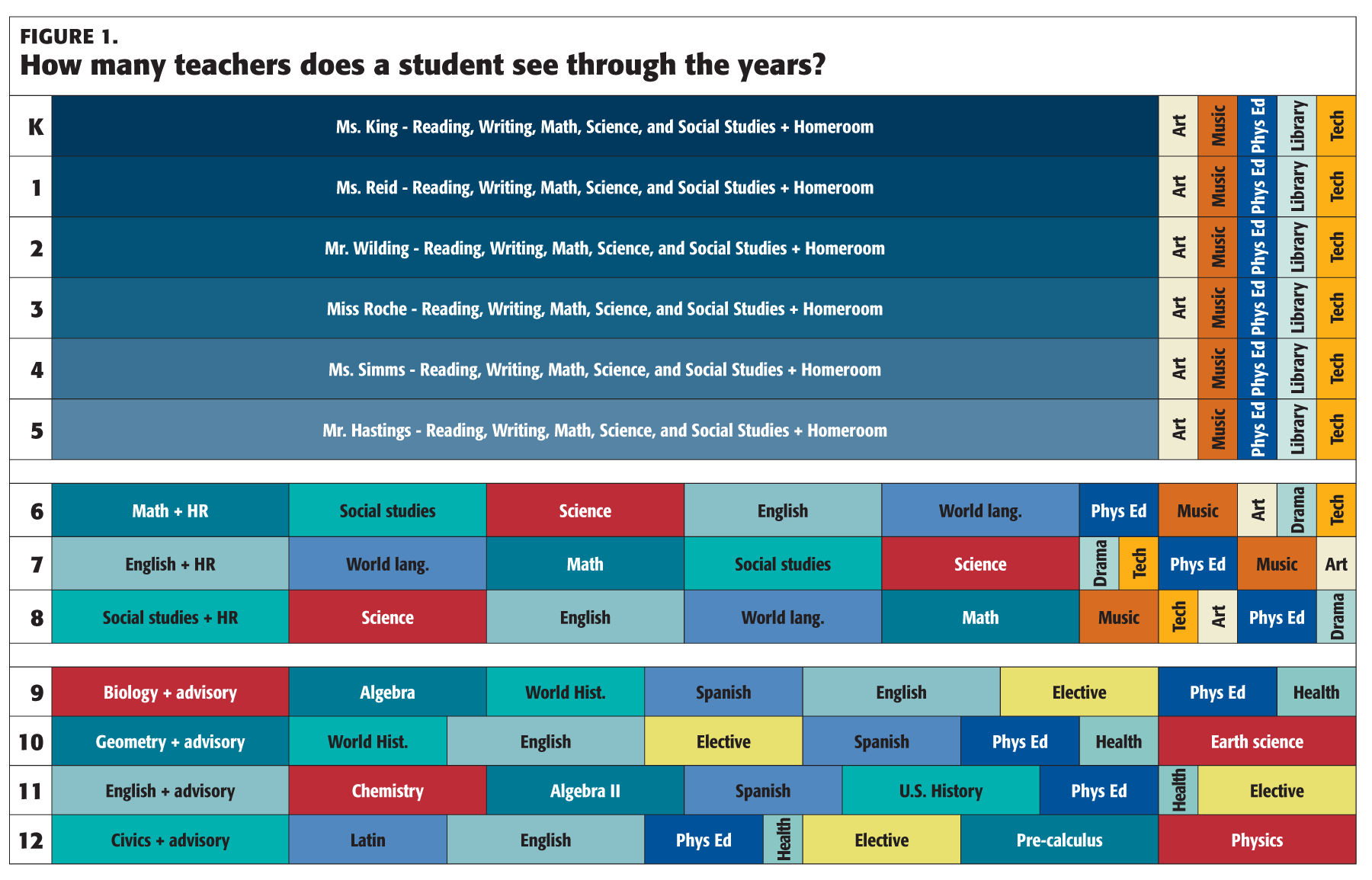

The graphic below shows a hypothetical student’s journey from kindergarten through 12th grade. In each year, the width of the rectangles represents the proportional amount of time that each teacher spends with this student. Elementary classes in this scenario are self-contained, with the student leaving the homeroom to go to a different specialty class once a week — art, music, physical education, library, and computer. In middle school, major subjects are departmentalized, and the student has a world language and a special each day, as well as homeroom handled by one of the core teachers. In high school, the student has a daily elective and world language, health and physical education two or three times a week, and an advisory group with one of his or her major-subject teachers.

What are some takeaways from this visual display of one student’s time spent with individual teachers? For starters, look at the number of teachers a student has from kindergarten to graduation: potentially 66, and that’s not counting pullout and push-in teachers, administrators, athletic coaches, nurses, counselors, custodians, cafeteria attendants, security officers, tutors, volunteers, and others. All told, there might be as many as 100 different adults contributing to a student’s education. That’s a lot of cooks in the kitchen!

Ask yourself, how many of your teachers and other school adults do you remember fondly? Not so fondly?

Figure 1 also makes abundantly clear how much more time elementary teachers spend with students compared to teachers at the secondary level. A waggish high-school administrator in New York City looked at Figure 1 and said, “It’s all the elementary teachers’ fault!” For good or ill, elementary teachers can have a major effect on individual children, while middle- and high-school teachers see more students less often, affecting four or five times as many students in a less time-intensive, more subject-specific way. Teacher-parent contact and communication also tend to be less frequent at the secondary level.

However, all K-12 teachers’ efforts combine to teach the skills and knowledge that students will take into their adult lives — all those lessons, discussions, worksheets, lectures, demonstrations, projects, labs, compliments, reprimands, push-ups, museum visits, homework assignments, quizzes, and tests that teachers orchestrate period by period, day by day, week by week, month by month, year by year, totaling about 15,000 hours from kindergarten through high school. Everyone contributes in some small way to growing students up.

“In some small way” sounds like an individual teacher’s contribution isn’t that significant. On the contrary, one teacher can have an outsize effect. As he moved through the elementary grades, my son David Marshall seemed to be locked into a math/science trajectory; his route was altered by studying with a single high school history teacher, and David is now a history teacher. Conversely, a colleague tells me that when her husband was in 2nd grade, a teacher said his handwriting was atrocious, and he would never amount to anything. Decades later, this man still broods about the comment and is painfully insecure about his writing. It’s impossible to predict which teachers will have this kind of life-changing effect on which students, but we know it happens in every school.

Is it only the extraordinary or cruel teacher who has such an outsized effect on students? Definitely not; the day-to-day work of every teacher matters, especially when it’s compounded in the next grade and the grade after that. Studies have shown that when students have an effective or highly effective teacher three years in a row, the long-term effects on achievement and life chances are significant, and the more good teaching a student has, the bigger the effect. The opposite is true if students have less-than-effective teachers several years in a row. That combination is especially devastating for students who walk into school with any kind of disadvantage — a learning disability, second-language challenges, conflict between parents at home, childhood trauma. These students especially need effective teaching and are disproportionately harmed by mediocre and ineffective teaching.

How to lead when so many exert influence?

Richard DuFour and Mike Mattos summed up the mission of schools in one sentence: “The key to improved student learning is to ensure more good teaching in more classrooms more of the time” (2013). This leads us to another takeaway from the K-12 school depicted in Figure 1: the daunting challenge faced by school leaders charged with coordinating and quality-controlling so many moving parts. How can principals ensure effective or highly effective teaching in all those classrooms? Each one of the teachers in Figure 1 teaches about 900 lessons a year (five a day times 180 days in the average school year). Here’s what a school year looks like from the individual teacher’s perspective:

Administrators, often responsible for 25 to 35 teachers, are spread very thin. In a school with 30 teachers, that means keeping tabs on about 27,000 lessons, which is an impossible task. And yet the whole K-12 enterprise comes down to the quality of each lesson, accumulating over time. What’s a conscientious principal to do, given that teachers are on their own with students more than 99% of the time? A lot depends on teachers’ training, judgment, and professionalism — and on the supervision, evaluation, coaching, professional development, and collaboration that principals are successful in orchestrating.

A second administrative challenge suggested by Figure 1 has to do with curriculum coherence or the challenge of ensuring that as students move from one classroom to another, they learn the right stuff from all those teachers. Several commentators have quipped that schools are really a bunch of independent contractors loosely connected by corridors and stairways. Indeed, the autonomy and “academic freedom” that many teachers have are what makes teaching an attractive profession for independent-minded folks. That’s good for creativity and experimentation in classrooms, but if teachers are allowed to decide what they teach as well as how they teach it, students are going to emerge from high school with Swiss cheese holes in their knowledge and skills, and they’ll pay the price later on.

When my daughter Lillie Marshall was teaching at Charlestown High School in Boston, she had a student who was shocked when he learned about the Holocaust for the first time.

This is hardly the only case of a student with important gaps in knowledge and skills. For students to graduate from 12th grade truly well-educated, schools need to orchestrate a thoughtful progression of skills and knowledge — what Robert Marzano calls a “guaranteed and viable curriculum” — ensuring that students learn what matters most and avoid wasting time on things they already know. The Common Core has brought a measure of order to the K-12 curriculum in most states, but many teachers have their own opinions about what’s most important and, de facto, have a measure of freedom to deviate from the required curriculum. Balancing the need for a solid grade-by-grade curriculum with the benefits of creativity and innovation at the classroom level (the perennial loose-tight dialectic) is one of trickiest parts of the principal’s job.

Look at the number of teachers a student has from kindergarten to graduation: potentially 66 — and that’s not counting pullout and push-in teachers, administrators, athletic coaches, nurses, counselors, custodians, cafeteria attendants, security officers, tutors, volunteers, and others.

A third leadership challenge is ensuring that every child is known and supported and doesn’t fall through the cracks. In the elementary grades, a lot depends on the relationships forged with those all-important homeroom teachers. In middle and high schools, there’s the danger of students not getting to know each teacher very well as they shuttle from one subject-area specialist to another. Administrators need to orchestrate regular teacher team meetings and ensure that they’re talking about their kids’ needs and how the curriculum connects across subject areas and with students’ lives. The best schools guarantee that every child is known well by at least one adult and make it their business to learn about students’ interests, widen their horizons, and spark new passions. The ultimate leadership challenge is synergy, or making all those adults’ contributions to students’ lives add up to more than the sum of the parts.

There’s another fact of life that’s not visible in any of our graphics: As each teacher’s year of 900 lessons progresses, student learning can be frustratingly slow. Dramatic Hollywood-style epiphanies are few and far between, and teachers must sometimes work for weeks or months before seeing measurable results. The challenge for teachers is to maintain the belief that their day-by-day work, joined with that of other adults inside and outside the school, will pay off. Patience, diligence, and a sometimes irrational faith are core requirements of the profession. And sometimes teachers are rewarded with the ultimate gift, a student who comes back years later and says that teacher made a lifelong difference.

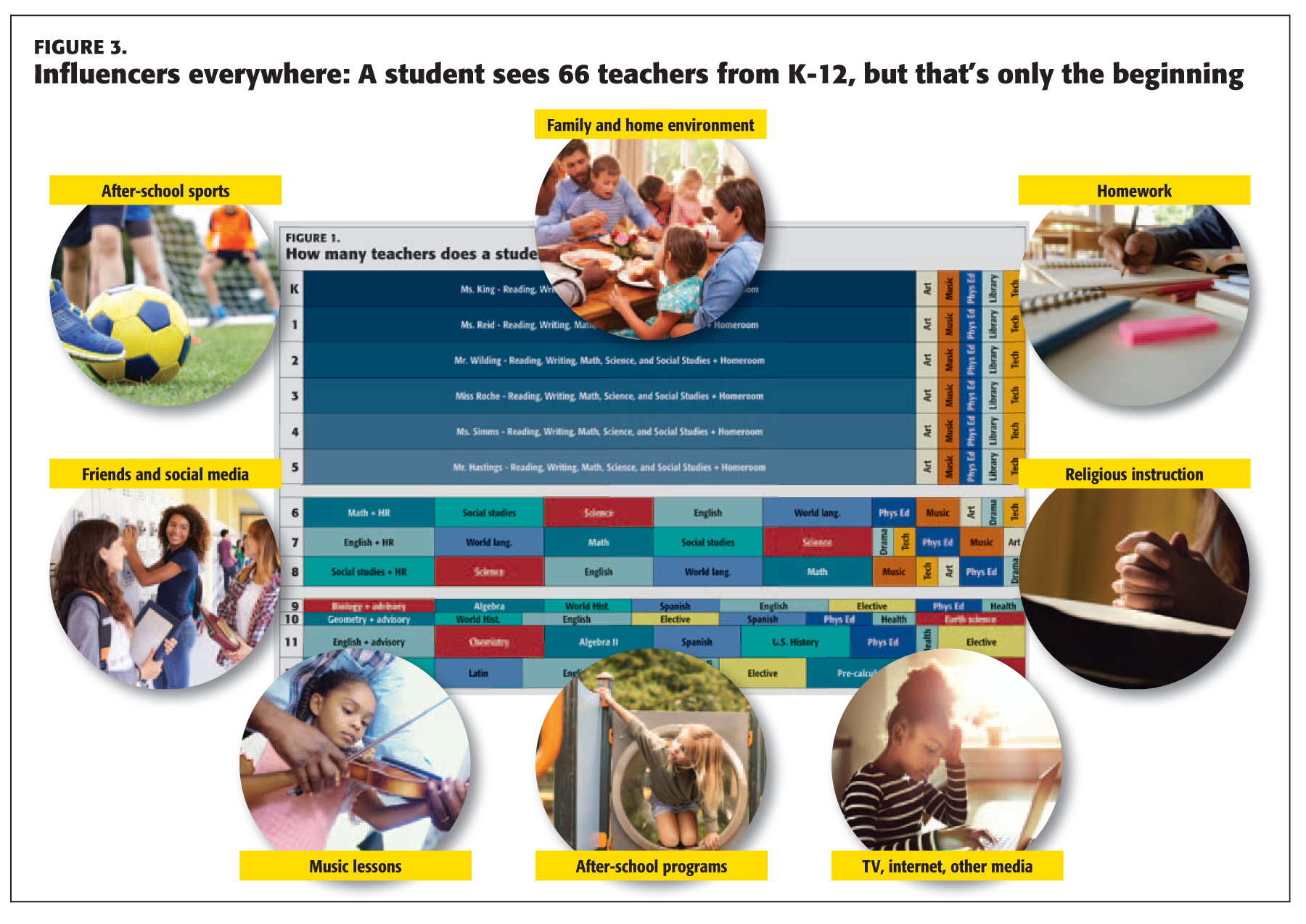

A final takeaway from the K-12 graphic is that educators have much more effect when they connect with what’s going on with students outside school. Figure 3 depicts another view of school life, showing an additional layer of influences on students’ lives, from family and home environment to social media and the internet. Educators somehow have to connect as many of the strands as possible, making sure that every child has the support to grow into a well-educated, decent human being.

Citation: Marshall, K. (2017). The big picture: How many people influence a student’s life? Phi Delta Kappan 99 (2), 42-45.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kim Marshall

Kim Marshall, formerly a Boston teacher and administrator, now coaches principals, consults, and speaks on school leadership and evaluation, and publishes the weekly Marshall Memo. He is the author of Rethinking Teacher Supervision and Evaluation (3rd ed., Jossey-Bass, August 2024).

Visit their website at: www.marshallmemo.com