The Common Core’s call for deep reading of complex text isn’t just for middle and high school students. Children in lower grades also can benefit by taking on challenging texts — with the right scaffolding and teacher guidance.

The Common Core’s call for deep reading of complex text isn’t just for middle and high school students. Children in lower grades also can benefit by taking on challenging texts — with the right scaffolding and teacher guidance.

The Common Core State Standards have cast a renewed light on reading instruction, presenting teachers with the new requirements to teach close reading of complex texts. The first standard in the reading domain requires that students “read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text” (NGA/CCSSO, 2010, p. 10).

Who wouldn’t want their students, much less their own child, to be able to do this? When readers read closely, they investigate, interrogate, and explore the deep meanings of a text. They form opinions and arguments based on a range of texts that have been examined and can defend their positions as a result. It’s the kind of reading that college professors expect of students — not to mention the type of reading necessary for jobs in the information age. Brown and Kappes (2012) define close reading as “an investigation of a short piece of text, with multiple readings done over multiple instructional lessons . . . students are guided to deeply analyze and appreciate various aspects of the text, such as key vocabulary and how its meaning is shaped by context; attention to form, tone, imagery, and/or rhetorical devices . . . ” (p. 2).

To be effective, teachers should integrate close reading into an instructional framework. Students still need modeling from teachers and opportunities to collaborate with peers to solve problems. Students also need to complete individual assignments that allow them to demonstrate their understanding. In other words, they still need high-quality instruction. Elementary school students need instruction in foundational reading skills. These younger readers must develop a solid base that includes phonemic awareness, alphabetics, phonics, and fluency. Close reading can’t replace all of this instruction. Instead, close reading provides students an opportunity to apply what they have learned to complex texts.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much agreement about the critical components of close reading lessons or if it even works. Some argue that close reading is untested, while others are concerned that close reading is not feasible for all students. After all, before adopting the standards, close reading was mostly used in college and with high school juniors and seniors enrolled in advanced coursework.

But what if it works for younger and less academically skilled students? What if close reading, when integrated into a cohesive instructional framework, creates students who read more and better? Is it possible that grappling with a complex text might result in higher achievement? Could it be that the expectations widely held for those students were in fact too low?

There is emerging evidence that close reading is effective with a broader audience of readers. Fisher and Frey (2014) demonstrated the effectiveness of close reading as an intervention for low-performing 7th and 8th graders. The 100 students who participated in that study via an after-school close reading effort significantly outperformed a comparison group of over 300 students on the state accountability assessment and on their reading self-perceptions and attendance in the after-school program.

Close examination of text can result in higher levels of learning for younger students as well. Williams and her coauthors (2014) studied 197 at-risk 2nd-grade social studies students who read, discussed, and analyzed texts written at 3rd- or 4th-grade levels. The researchers found “that the students who were taught text structure performed significantly better both on text that had been used in the instruction and also on novel text that they had not encountered before, which is, of course, what is meant by reading comprehension” (p. 12). The authors concluded that while students in this study had not yet mastered word recognition and fluency, they posted gains anyway and therefore “should not be deprived of the opportunity to receive instruction that would provide a strong foundation for later learning” (p. 13). While not a study specifically on close reading as an instructional routine, this research advances the position that careful examination of the structure of informational text above students’ reading level is worthy.

Instruction with challenging text

Teachers and administrators should consider a number of essential features of close reading. We’ve grouped these into four major categories: short, complex texts; rich discussions based on worthy questions; revisiting and annotating the text; and being inspired by the text. Educators should consider these the look-fors that deepen student interactions with text.

#1. Short, complex texts

Text selections used in close reading are typically short, although they need not be stand-alone. We fear that, in too many cases, teachers are scouring resources looking for a complete piece that is less than 200 words long. But the intention of close reading is to zoom in on a passage that is worthy of examination and discussion. A longer text may offer a few paragraphs where the author lays out his thesis or a pivotal scene that might be otherwise misinterpreted or overlooked. Close reading provides a platform to zoom in on a shorter passage in order to build understanding of the text as a whole. This is especially important as readers will need to reread the text, digging deeper into the meaning. A text that is too long may stifle repeated reading.

Complexity is another element of a close reading. Texts must be considered across three factors: quantitative measure, qualitative values, and the match between task demand and reader (NGA/CCSSO, 2010). The first two address the nature of the text itself. Quantitative measures are calculated using a formula that includes average sentence length and the number of rare words. Qualitative values include the levels of meaning and purpose, the text structures used, the degree that the language is conventional and clear, as well as the knowledge needed to understand it. Beyond the characteristics of the text itself are questions about who will read it and the degree of support they’ll need to do so. These are the reader and task factors; taken together they help the teacher determine whether the student will need a low degree of scaffolding (e.g., independent or collaborative reading) or a high degree of scaffolding (close reading or a read-aloud). Text selected for close reading requires a moderately high degree of teacher support through questioning, discussion, and repeated readings, and thus will stretch comprehension skills. Conversely, text selected for independent or collaborative reading requires less teacher scaffolding, allowing students to practice comprehension skills that already have been taught many times. These reading events give students time to consolidate their ability to think critically outside the teacher’s presence.

#2. Rich discussions based on worthy questions

A hallmark of close reading is the extended discussion students have with one another. If the text is complex enough, students will need time to talk with others about their developing and deepening understanding of it. Of course, they need to be taught how to have these conversations and what to do when they get stuck. But collaborative conversations themselves can unlock a text for students. That’s not to say that one student understands the text and tells the others what to think about it but rather that they discover the meaning of the text as they interact with one another.

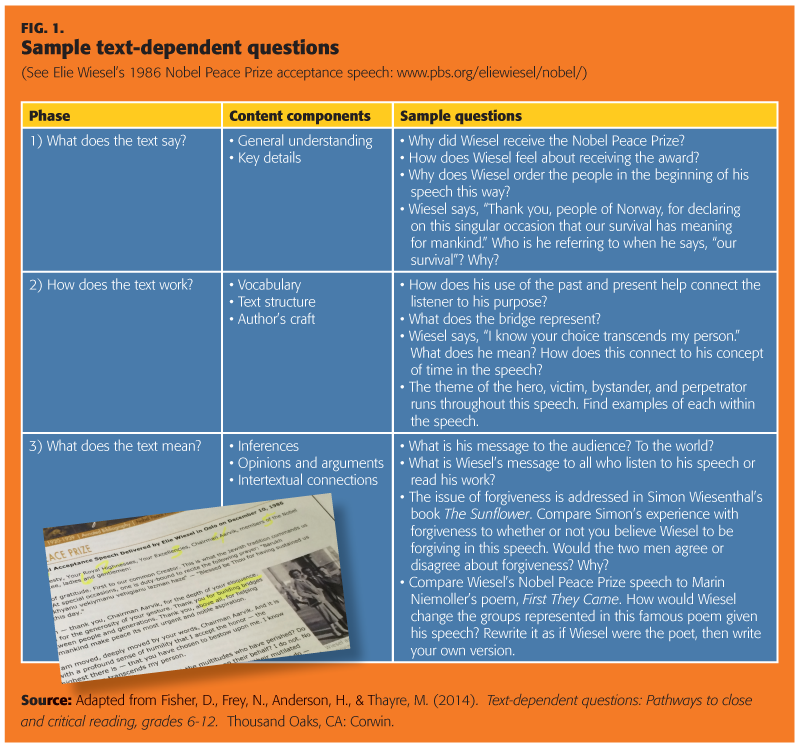

Close readings are guided by questions that intentionally deepen as students interact with the text. The best close reading lessons we see systematically lead students from the literal level to structural level to inferential level. We use guiding questions for teachers so they can plan the content of their questions. The three guiding questions we use are:

- What does the text say?

- How does the text work?

- What does the text mean? (Fisher et al., 2014).

The literal-level questions (what does the text say?) focus on general understanding and key ideas. The structural-level questions (how does the text work?) focus on vocabulary, text structure, and author’s craft. And finally the inferential-level questions (what does the text mean?) focus on logical inferences, text-to-text connections, and the opinions and arguments that can be made based on the text.

Figure 1 contains a sample list of content questions for each of these levels based on the Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech delivered by Elie Wiesel (1986) in Oslo, Norway. Imagine the student conversations as they deepened their understanding of this speech. Rather than have their teacher tell them what to think about the text, they have to consider what the text offers and then use that information as they discuss their thinking. (Our YouTube channel has several close reading videos that show such student interactions: www.youtube.com/user/FisherandFrey)

It’s important to note that teachers don’t necessarily ask all of the questions they have developed. We like to think of text-dependent questions as fodder for conversation and suggest that they are only brought out of the metaphorical back pocket when student discussion falters. Teachers also move up to the next level of questions when students have sufficiently demonstrated understanding at a level. There’s no reason to linger at the literal level if students have demonstrated their understanding. Teachers must pay attention to students’ thinking and understanding so that they know when to take the conversation, and thus the thinking, deeper.

#3. Revisiting and annotating the text

Another expectation of close reading involves rereading and marking up the text. Students have successive and deepening interactions with text as they move from the literal to the structural to the inferential level. That doesn’t happen on the first read and may not even happen on the third read of the text. We can’t predict how many times students will need to reread the text to get to the inferential level of understanding, but we know that a single read isn’t likely to do the trick. With appropriate support, rereading can do the trick because accessing a text multiple times improves fluency and comprehension (Therrien, 2004).

However, we were sensitive to the comments of Nichols, Rupley, and Rasinski (2009) who suggested that “[c]ontinual reliance on repeated readings without appropriate guidance and support can lead to diminished student engagement and may not help students recognize that increased fluency provides for more focus on meaning” (p. 5). The guidance and support necessary in a close reading lesson includes the collaborative conversations students have with one another as well as the questions they or their teachers ask about the text. Students will reread a text when they are provided a new purpose, an interesting question, or if they are pressed for evidence.

When students understand that they’re expected to produce evidence from the text to support their responses, they start to take notes about the text. Rather than teach annotation skills in isolation, wise teachers press for evidence and show students how annotations would have helped them quickly locate the evidence. We have narrowed the wide range of possible annotation marks to three because students need a lot of instruction in these to develop a habit. Once they have reached automaticity with these three, teachers can provide additional instruction in a wider range of annotations, such as those recommended by Adler and Van Doren (1940/1972). The three we recommend are:

- Underlining the central, main, or key ideas because this requires that students learn to note important information.

- Circle confusing or unclear words and phrases because this requires that students learn to monitor their understanding.

- Write margin notes in their own words because this requires that students learn to summarize and synthesize information.

#4. Being inspired by the text

A basic tenet of effective instruction is that it should result in student action. Throughout the school day students write, solve problems, investigate phenomena, discuss ideas with peers, and engage in further reading about topics. Close reading lessons are no different. After devoting significant time and attention to the inner workings of a complex piece of text, students need opportunities to act upon what has been learned and what new lines of inquiry it has inspired. Examples of actions include:

- Writing from sources;

- Debate or Socratic seminar;

- Investigation or research; and

- Formal presentation or extemporaneous speech (Fisher et al., 2014).

We used the word inspired deliberately because close readings should spark curiosity such that students can use what they have learned from the text to extend their inquiry using a number of pathways. Arguably the most common action after reading is to respond in writing. However, the nature of writing is changing as well. Where once personal responses were dominant in many classrooms, students now are being asked to write across three text types: narrative, informational/explanatory, and argumentative. These text types are used in debates and Socratic seminars as students wrestle with challenging ideas that have been posed in the literary and informational texts they have read.

Discussions during close reading lessons generate new questions for students. It is helpful to anticipate when such investigations are likely. For instance, a 5th-grade unit on ecosystems in science that includes a reading about the effects of ocean acidification on sea life is likely to inspire further questions. Which species are most vulnerable? What possible solutions might reserve or slow the effects? These investigations can result in further readings, extemporaneous speeches to report findings, and even formal presentations to the class.

Conclusion

School administrators and teacher leaders are charged with fostering the use of innovative practices to improve student achievement. Close reading as an instructional routine is a more recent practice in K-12 classrooms, and the field as a whole is still determining what constitutes effective implementation. As with all new instructional routines, there are questions about who benefits and under what conditions. As teachers craft close reading lessons in their classrooms, they need to keep in mind that the early evidence is that both younger and older students can benefit from this instruction. However, close reading should never be perceived as the single answer for reading development. All students need a range of experiences with a range of texts, and elementary students need reading foundational skills developed parallel to their comprehension skills.

Teacher scaffolding and involvement are at the heart of close reading of complex texts because they are essential for driving student discussion about text-dependent questions. Most of all, the attention devoted to close reading should result in action as students are inspired to talk and write about topics under investigation. Familiarity with the essential components of close reading can support the work of administrators and mentoring teachers.

References

Adler, M.J. & Van Doren, C. (1940/1972). How to read a book. New York, NY: Touchstone.

Brown, S. & Kappes, L. (2012). Implementing the Common Core State Standards: A primer on “close reading of text.” Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute.

Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2014). Close reading as an intervention for struggling middle school readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57, 367-376.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., Anderson, H., & Thayre, M. (2014). Text-dependent questions: Pathways to close and critical reading. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Washington, DC: Author.

Nichols, W.D., Rupley, W.H., & Rasinski, T. (2009). Fluency in learning to read for meaning: Going beyond repeated readings. Literacy Research and Instruction, 48 (1), 1-13.

Therrien, W.J. (2004). Fluency and comprehension gains as a result of repeated reading: A meta-analysis. Remedial & Special Education, 25 (4), 252-261.

Wiesel, E. (1986). Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech. Oslo, Norway: Author. www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/nobel/

Williams, J.P., Pollini, S., Nubla-Kung, A.M., Snyder, A.E., Garcia, A., Ordynans, J.G., & Atkins, J.G. (2014). An intervention to improve comprehension of cause/effect through expository text structure instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106 (1), 1-17.

Originally published in the February 2015 Phi Delta Kappan, 96 (5), 56-61. © 2015 Phi Delta Kappa International. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Douglas Fisher

DOUGLAS FISHER is a professor of educational leadership at San Diego State University and a teacher leader at Health Sciences High & Middle College, San Diego, Calif.

Nancy Frey

NANCY FREY is a professor of educational leadership at San Diego State University.