The nation’s largest civil rights organization steps up its opposition to charter schools just as a president and new education secretary appear ready to kick the sector into high gear.

The nation’s largest civil rights organization steps up its opposition to charter schools just as a president and new education secretary appear ready to kick the sector into high gear.

by Joan Richardson

AN INTERVIEW WITH JULIAN VASQUEZ HEILIG

KAPPAN: What’s your perspective on what led the NAACP to conclude that a moratorium on the expansion of charter schools would be in the best interest of students of color?

HEILIG: If you examine their resolutions over the years, the membership of the NAACP has taken several critical stands on charters. I believe that’s been a response to the fact that there’s been an enormous growth in charters over the past two decades. The federal government alone has spent $3.3 billion on charter schools over the past 10 years. We’ve also seen a doubling of charters over the past few years. There are 6,800 charters across the United States that enroll nearly 3 million children. Charters aren’t really a boutique thing anymore.

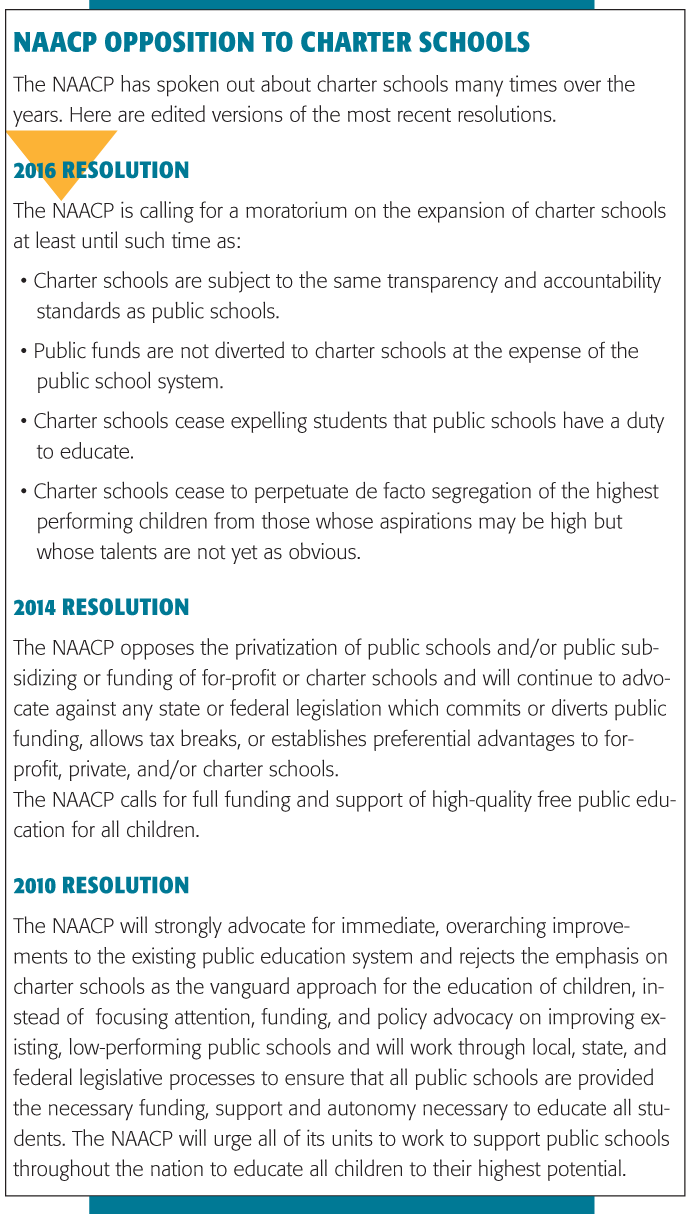

So the 2010 resolution by the NAACP first said that we needed to take a really hard look at charters, even saying that they are separate and unequal. In 2014, they passed another resolution equating charters with the privatization movement. So this is really a critique that the NAACP has made over the years.

So the 2010 resolution by the NAACP first said that we needed to take a really hard look at charters, even saying that they are separate and unequal. In 2014, they passed another resolution equating charters with the privatization movement. So this is really a critique that the NAACP has made over the years.

The NAACP is not alone in taking this stand. Other civil rights organizations have also asked for a moratorium and discussed the role of charter schools in the education privatization movement — the Journey for Justice Alliance, an alliance of charter parents and noncharter parents in cities across the United States, and the Black Lives Matter Movement, which is the nation’s youngest civil rights organization. So you have the nation’s oldest and largest civil rights organization and the nation’s youngest civil rights organization coming together and another grassroots organization that includes charter school parents all speaking in unison.

I also think it’s important to remember that school choice came to prominence when white academics sought to influence the national conversation about desegregation and public education after Brown v. Board of Education. The initial push for school choice was not to improve the success of minority students in the United States. In fact, the academics who recommended school choice envisioned a public education system built around parent-student choice, school competition, and school autonomy as a solution to what they saw as the problem of direct democratic control and governmental intervention in public schools. In the South, school choice was used for “all deliberate slowness” after Brown to ensure that black children would not go to school with white children. So abuse of school choice has long been a civil rights issue.

KAPPAN: What’s striking about the 2016 resolution is its emphasis on the moratorium and the language about the expansion of charter schools. What’s not as clear is whether this means that the NAACP supports or opposes the concept of charter schools or whether the opposition to charter schools is just to create more of them too quickly. Can you clarify that?

KAPPAN: What’s striking about the 2016 resolution is its emphasis on the moratorium and the language about the expansion of charter schools. What’s not as clear is whether this means that the NAACP supports or opposes the concept of charter schools or whether the opposition to charter schools is just to create more of them too quickly. Can you clarify that?

HEILIG: I don’t think any of the civil rights organizations have said that we need to close all 7,000 charter schools by tomorrow. The critique has been that there are issues in charter schools and that charter schools haven’t acted substantively to address the critiques. For example, they are paying lobbyists millions of dollars to ensure that in California we don’t have access to discipline data or to teacher attrition data. They appear to be tone deaf to concerns raised by parents and by the African-American community. That’s really disconcerting. It’s been a good outcome that the calls for a moratorium have finally gotten their attention.

The charter movement really hasn’t engaged in these conversations in ways that have been productive in terms of more transparency and accountability for students of color who attend charter schools. Thus, you see this response because charter and noncharter parents are concerned about equity and access issues and the financial malfeasance in the charter sector.

There’s a concern because, on the one hand, charter schools are saying that we condemn the bad apple charter schools. But, on the other hand, charter lobbying organizations and the foundations are spending hundreds of millions of dollars in ways that don’t seem to be all that concerned about the bad apples when it comes to transparency and accountability and protecting the civil rights of students. Why do they continue to ignore those issues?

KAPPAN: Is this new resolution backtracking on the 2010 resolution in any way? Does this language about the moratorium say that the NAACP is more accepting of the concept of charter schools but that it just doesn’t like the execution of them?

HEILIG: My perspective is that the resolutions passed by the NAACP actually build upon themselves. As the NAACP has continued to pass charter resolutions, the membership appears to be demonstrating that charter schools should not be our primary approach to educational policy. The concern has grown because the number of charter schools have grown. Charters have evolved, they are not being sold as a limited approach anymore. For some people, privately controlled charter schools are the educational policy approach that they prefer for the majority of schools.

The new administration

KAPPAN: When the NAACP passed this resolution, there may have been an expectation that Hillary Clinton would be the next president. Of course, that did not happen. Not only do we have a president who’s a proponent of charter schools, but we also now have an incoming secretary of education, Betsy DeVos, who has actively supported charter schools. I wonder how that selection is going to change this discussion.

HEILIG: With a Trump administration, this resolution has more importance than ever before because he’s said that he’s going to pump billions of dollars into charter schools and vouchers, which are really partner market-based school choice approaches.

It’s also important because DeVos’s view of what a charter school means is antithetical to what many “education reformers” support. Trump is supporting forms of parent choice and privatization that are beyond what even the Democratic education “reformers” have been supporting. So it remains to be seen if the reformers move toward Trump or if they continue with their argument that there are some good charters but that these other forms of market-based choice are not desirable.

Charters have not satiated the privatization and private-control proponents. In fact, it has become readily apparent that charter schools were just the initiation of the conversation for private control and privatization in other forms such as vouchers.

Trump’s election may turn the tide in favor of private control and privatization of public education. Donald Trump promised in the campaign that his administration would pass the School Choice and Education Opportunity Act and perhaps spend billions on school choice in the first 100 days. So while the NAACP and many in the civil rights community may be supporting community-based, democratically controlled education, the bully pulpit of the presidency may enforce a new era of private control and privatization of the public education system.

KAPPAN: The NAACP is engaging in listening tours across the country as a way to learn more about what parents and others have to say about charter schools. Which way is the public discussion heading on charter schools?

HEILIG: Parents are feeling more empowered to speak out about their experiences with charter schools. And, for the first time, the media is taking a more critical look at charter schools.

What’s happening is that Americans are engaging in conversation about charter schools in a way that we haven’t before. For a long time, there was only positive conversation about charter schools. For a long time, if you said charter schools, it was like you were talking about sprinkling magical fairy dust on a school.

Evolution in thinking

KAPPAN: You worked at a charter school for a while. When you took that job, you must have had some belief that charter schools were providing a good education for children. But your views about charter schools have changed quite a lot. Tell me more about your personal relationship with charter schools.

HEILIG: I’m a former charter school parent, I was a charter school educator, I was on a charter school board, I donated to charter schools, I volunteered at a charter school.

Yes, I totally agreed with the charter school approach. I believed the hype. That was the only message that had been communicated to me in the public discourse. I had never heard that there were problems with charter schools. I was unaware of any critiques. I wasn’t really aware of the role of charters and privatization.

As I got involved with a charter school in Texas, I started to dig a little deeper. My curiosity drove me to learn more. That’s when I started to research charter schools. There was a decade of research documenting all sorts of different issues in charter schools but nowhere was that being discussed in popular culture or the media. What I found in the peer-reviewed research literature was really troubling to me because it wasn’t part of the public discourse. So it actually became part of my research agenda, and I changed my mind about charter schools.

Potential for quality education?

Potential for quality education?

KAPPAN: If charter schools were to meet the standards laid out in the NAACP resolution — if they were more transparent, if they were more accountable, if there were no discipline issues, if there was no segregation of children — do you think they could provide the kind of quality of education that American children are entitled to have?

HEILIG: No. I don’t think the private control of schools is in our national best interest writ large. As a boutique approach, I don’t think it’s highly problematic. But when private control becomes the agenda for improving schools, that’s a problem for our democracy.

There’s a whole set of people who don’t see education as a public commons anymore. They don’t view education as a publicly provided good and instead believe that corporations and churches should be doing it instead with public money. They have a motley alliance with those who believe that charter schools address civil rights.

We haven’t closed many charter schools because of underperformance. We’re continuing whole hog down this path even though we know that many charter schools are underperforming, charter schools are worse on discipline in many states, they often have lower test scores, and higher levels of racial segregation. But we just continue down this road. The politics and spin of the conversation has overwhelmed the facts.

We should talk more about the alternative. The alternative is innovative forms of democratically controlled schools such as open-enrollment magnets, in-district charters, and community schools with wraparound services.

Privatized choice is not in the best interest of students. When corporations and churches control the schools, which is the ultimate goal of neoliberal approaches to markets, they control the conversation. They determine who can and cannot attend their schools. And it is not in the best interest of poor children to create a system that allows corporations and churches to make those decisions about individual students. It’s in the best interest of our democracy to ensure that all schools are open to all children.

We’ve done a terrible job of talking about why charter schools privately controlling public money is becoming more problematic. The core of the conversation is this: If we don’t pay attention to the democratic control of our schools, democracy could not only die in our schools, democracy could die in our communities.

Originally published in February 2017 Phi Delta Kappan 98 (5), 41-44. © 2017 Phi Delta Kappa International. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joan Richardson

JOAN RICHARDSON is the former director of the PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools and the former editor-in-chief of Phi Delta Kappan magazine.